Queer Yale EphemeraMax Walden ’11 PHD ’18 & Nick Robbins ‘10

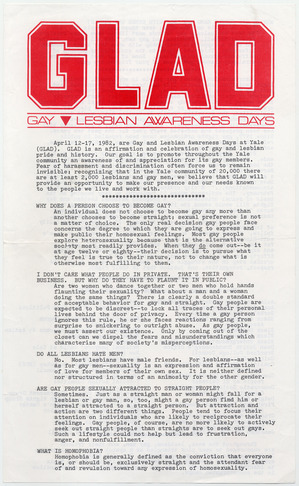

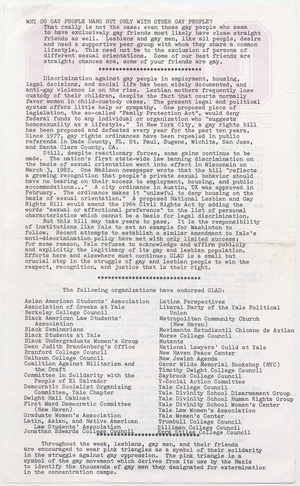

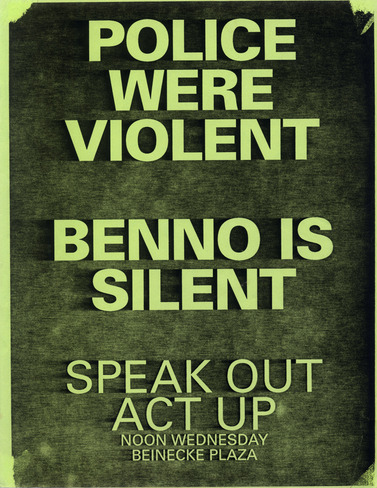

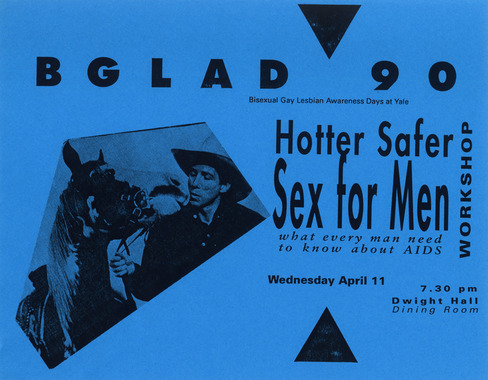

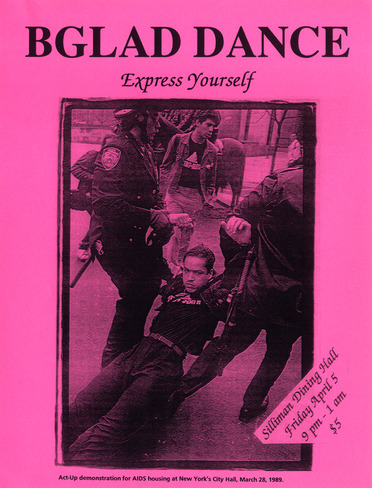

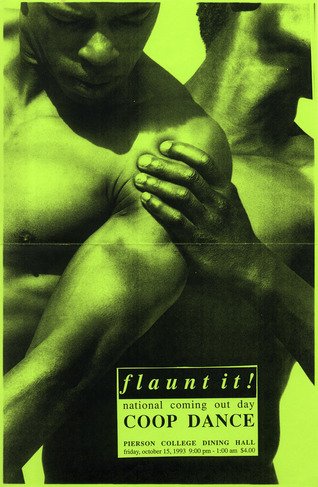

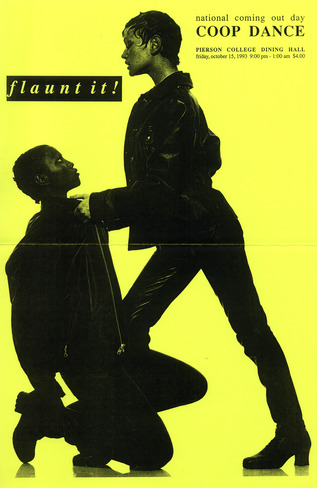

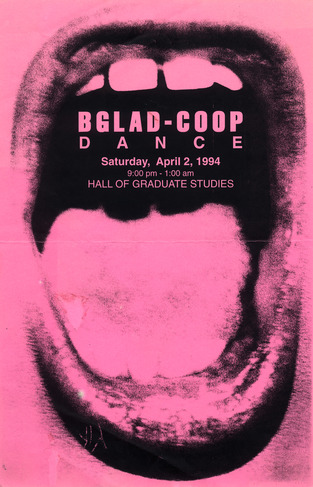

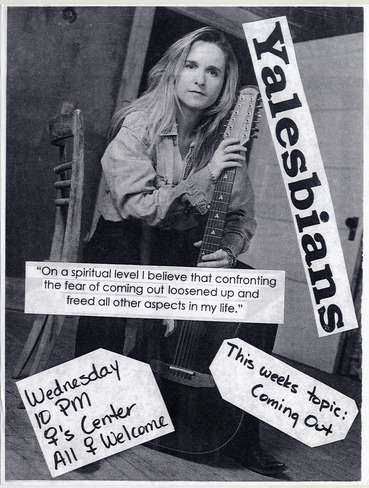

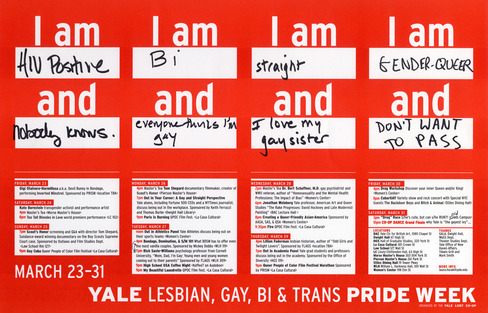

Gay life at Yale was transformed in 1969, when undergraduates founded the university’s first LGBTQ student organization. Established as the Homosexuality Discussion Group, it still exists today as the Lesbian, Gay, Transgender, and Queer Cooperative at Yale (or LGBT Co-op for short) and continues to support educational and social events on campus. The images from this photo essay are reproductions of ephemeral material held in the Co-op’s collections at Manuscripts and Archives, which collects and preserves primary sources relating to Yale’s history. Together with the timeline of university history, this collection of posters, pamphlets, and photographs is meant to reflect Yale’s vibrant queer culture of the 1980s and 1990s, just as AIDS was beginning to affect the community. 1. Gay and Lesbian Awareness Day Poster, 1982 — First held in 1982, Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days (GLAD) was one of the most important annual events sponsored by the Co-op. This flier outlines GLAD’s mission in its inaugural year: “to promote throughout the Yale community an awareness of and appreciation for its gay members.” 2. Event poster, 1983 — A poster promotes a Co-op sponsored safe sex workshop for men who have sex with men. 3. Gay and Lesbian Awareness Day schedule of events, 1984 — This poster outlines the events offered at the 1984 Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days. Events include poetry readings by Judy Grahn and a discussion of ‘Style’ led by Quentin Crisp. 4. Yale Co-op group picture, 1986 — Members of the Yale LGBT Co-op pose for a group photograph outside of Berkeley College. 5. Cover of the Gay and Lesbian Studies Pink Book, 1993 — Gay and Lesbian studies became an officially-recognized academic discipline at Yale with the establishment of the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies in 1987. Published annually, the Center’s “Pink Book” (the 1993-4 edition of which is shown here) acts as a supplement to the undergraduate course catalogue. 6. Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Awareness Days (BGLAD) handout, 1988 — A small handbill prepared for GLAD 1988 (rechristened BGLAD to be more inclusive) explains the significance of the pink triangle. 7. Rally poster, 1989 — In 1989, an altercation broke out between attendees at the university’s third annual Lesbian and Gay Studies Conference and members of the Yale and New Haven police departments. Several Yale students were arrested and charges of police brutality and administrative suppression of free speech followed. This poster promotes a rally against university president Benno Schmidt’s allegedly inadequate response to the incident. 8. BGLAD event poster, 1990 — A poster for BGLAD 1990 advertises a safe sex workshop for men. 9. BGLAD dance poster, 1991 — A poster advertises the 1991 BGLAD dance. Such dances were an integral part of social life at Yale in the 1980s and 1990s, when LGBTQ students lacked officially-designated spaces to gather. Attendance at the annual BGLAD dances often approached 500 students. 10-12. Co-op dance posters, 1993, 1993, 1994 — Two 1993 and one ’94 posters advertise Co-op sponsored dances. 13. Yalesbians poster, n.d. — A poster advertises a discussion on coming out sponsored by the student group Yalesbians. 14. Pride Week, 2001 — A poster advertises the Co-op’s annual Pride Week, a later incarnation of the GLAD events of the 1980s and 1990s.

— Max Walden ’11 PHD ’18 & Nick Robbins ‘10

PDF verion

Print / Save as PDF

|

AIDS at Yale: A History.Chris Glazek ’07

Cover of The New Journal, a Yale undergraduate publication, from February 1995. The issue included articles on the Yale-New Haven Pediatric AIDS ward, the Connecticut AIDS Residence Program for HIV-positive homeless persons, and on the work of Al Novick, innovative AIDS researcher at Yale. On June 5, 1981, the Center for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report announced a strange outbreak among five young men in Los Angeles. The men had come down with Pneumocystis Carinii pneumonia, a rare disease normally forestalled by a healthy immune system. Another unusual feature linked the men: all were gay. The following month, the CDC reported an outbreak in New York of Kaposi’s sarcoma, an uncommon cancer typically associated with elderly men of Mediterranean descent. Again, the patients were all gay men. Later that year, another outbreak of rare diseases was noticed among heroin addicts. And in 1982, similar outbreaks were recorded among hemophiliacs, next among Haitians, and finally among female partners of drug-users and their children. Although the original MMWR report speculated that sexual contact “or some aspect of a homosexual lifestyle” may have played a role in the initial outbreaks, it was three years before the ultimate cause of these unusual illnesses was traced back to HIV, a virus transmitted through semen, vaginal and anal fluids, and blood. In the meantime, people were dying: 121 Americans in 1981, 447 the next year, and 1,476 the year after. In 1990, 31,120 Americans died of AIDS. To date, more than 600,000 men and women living in the United States have perished from AIDS. Several hundred of them were alumni, faculty, and staff from Yale University. As long as there has been an AIDS crisis, Yalies have been at the front lines. Months before the first report from the CDC, writer Larry Kramer ‘57 noticed with alarm that many of his friends from Fire Island, the Long Island enclave where Kramer summered in the seventies, were contracting strange and terrible diseases. In the fall of 1981, Kramer invited eighty prominent acquaintances to his Manhattan apartment to hear Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien MED ‘60, one of the first AIDS investigators. Friedman told them that their friends’ deaths were connected to one another, and that they needed to take action. That gathering spawned Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the country’s first AIDS service organization and still one of the most important. By 1983, most New Yorkers, gay and straight, still had no idea that the AIDS era had begun. Frustrated, Kramer wrote a cover story for the New York Native titled “1,112 and Counting,” which became a rallying cry for those concerned about a disease that at that time was still called Gay-Related Immune Deficiency—”gay cancer.” Kramer’s piece opens, “If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in real trouble. If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get.” Four years later Kramer helped to found the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), a protest organization that used civil disobedience and direct action to obtain support for fighting the epidemic. While Kramer was sounding the alarm about “gay cancer” in New York, another Yale alumnus, Tim Westmoreland LAW ‘79, used his position as a congressional staffer on the House Subcommittee on Health and the Environment to arrange the first federal probe into AIDS-related diseases. At a hearing on April 13th, 1982, the subcommittee chairman, Representative Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), read a speech written by Westmoreland decrying the lack of attention paid to GRID, especially in comparison to the vigorous efforts undertaken in the late seventies to combat Legionnaires’ disease, which had claimed only a handful of lives. “There is no doubt in my mind,” said Waxman, “that if the same disease had appeared among Americans of Norwegian descent, or among tennis players, rather than gay males, the responses of both the government and the medical community would have been different.” His conclusion was stark: “What society judged was not the severity of the disease, but the social acceptability of the individuals affected.” What little federal funding was made available for AIDS research during the Reagan years can be traced back to Westmoreland’s efforts and Waxman’s committee. Among the first people on Yale’s campus to appreciate the magnitude of the problem facing the country were William Sabella SPH ‘83, a graduate student in the School of Public Health, and his partner Alvin Novick, a biology professor. In the spring of 1982, Sabella and Novick’s best friend, a radiology resident at Yale Medical School, fell ill. That summer, after attending a GRID conference sponsored by the National Gay Health Education Foundation, Novick decided to dedicate the rest of his life to fighting the new disease. Novick came out to his colleagues for the first time. In the fall of 1982, Novick arranged a meeting with Yale’s president, Bart Giamatti ‘60, to inform him that Novick intended to change the direction of his research. Novick was one of the world’s leading authorities on bats: he had made his name studying “echolocation,” the sonar-based mechanism through which bats become aware of space. Now Novick wanted to study GRID, which had already claimed the lives of several friends. Giamatti gave his blessing. The following summer, after a meeting with a group of friends at Partners Café, a New Haven gay bar, Novick founded AIDS Project New Haven, now the city’s largest AIDS service organization. Over the next several years, Novick became one of the country’s most prominent voices fighting for a more vigorous public response to the AIDS epidemic. Novick spoke up to nine times a week on what he called “AIDS 101,” while Sabella, became Connecticut’s state AIDS Coordinator, developing educational materials related to HIV. Never afraid to use his medical knowledge to influence policy debates, Novick served as head of the American Association of Physicians for Human Rights (now called the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association), catalyzed the creation of (and chaired) the New Haven Mayor’s Task Force on AIDS, and edited the journal AIDS & Public Policy. He also introduced two popular classes to Yale’s curriculum: “Bioethics” and “AIDS and Society.” Novick was among the first to advocate safeguards on blood supply for the commercial blood industry. He was an early supporter of needle exchange programs to help prevent the spread of the epidemic among intravenous drug users, and was a tireless debunker of the fear that medical professionals would get HIV by caring for AIDS patients. He opposed mandatory AIDS testing for medical professionals as a needless, alarmist expense, and he defended the rights of doctors living with HIV to practice medicine. In an interview with The New York Times in 1987, Novick said “We have to stop seeing this as anything other than a devastating infection. No one is guilty. Only the virus is guilty.” While Novick spent the early years of the epidemic trying to convince academics and politicians that the country had a major crisis on its hands, another faculty member, Joseph Bove, a professor of laboratory medicine, became a prominent opponent of mandatory screening for the nation’s blood supply. At a conference at New York University on March 17, 1983, Bove, who served as a spokesman for a blood industry group, controversially stated that the CDC’s evidence that AIDS had infected the country’s blood supply was “inferential” and “lacking.” Later that year, he told The Wall Street Journal that “more people are killed by bee stings” than by transfusions leading to AIDS. In fact, there had already been numerous cases of AIDS reported among hemophiliacs; several thousand would go on to die. While Kramer and Novick came early to AIDS, Yale students came late. Although by the early eighties the University already had a robust tradition of student activism around gay health issues, it wasn’t until mid-way through 1983 that “gay cancer” entered the Yale vocabulary. At the time, the prominent issue among gay student activists was Hepatitis B. In the spring of ‘83, a group of students led by George Chauncey ‘77 GRD ‘89 and affiliated with the Yale Gay and Lesbian Co-op launched a campaign to encourage the Yale health plan to offer the Hepatitis B vaccine for free. The University had made the vaccine available, but only to students willing to pay $106, a price that put it out of reach for many students and broke with the University’s usual policy, which was to offer vaccines for free. The University argued that subsidizing the vaccine was an unnecessary expense: after all, it argued, to be at risk for contracting Hepatitis B, you’d need to have a large number of sexual partners, or attend bathhouses, and the University could hardly imagine a Yale student falling into such a category. Unfazed, the student group staged a rally on Cross Campus, followed by a march and a silent picket outside university health services. The University agreed to reduce the price to $35. After the successful completion of the Hepatitis B campaign, the activists sponsored a public forum on gay health issues. The organizers had expected moderate turnout, but the meeting was mobbed, mostly by New Haven residents in their late twenties and thirties. This crowd was not interested in Hepatitis B. They wanted to know about gay cancer. The students running the event weren’t prepared to answer their questions. Ironically, gay sex was very much on the campus radar, much to the chagrin of segments of the University administration and alumni. Frequent gay dances and bouts of student activism made Yale’s LGBT community unusually visible and triggered fears in some quarters that the University was getting a reputation as a gay haven. In 1982, a student group affiliated with the Co-op circulated a petition to urge the University to add sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy. The Yale Corporation declined. Instead, it amended the policy to say that Yale would respect “attitudes on a variety of matters that are essentially personal in nature.” Frustrated by the University’s refusal to specifically acknowledge the rights of gay and lesbian students, the Co-op continued to pressure the administration. Four years later, under the leadership of Sarah Pettit ‘88, who went on to help found Out magazine, a new round of protests successfully convinced the university to add sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy. As the eighties wore on, the University’s discomfort with issues related to sexuality persisted. On October 27, 1989, nine people were arrested by police at the third annual conference of the Lesbian and Gay Studies Center at Yale, chaired by the historian John Boswell. While the opening lecture was going on, police arrested Bill Dobbs, a New York City lawyer, for putting up posters with images from a sex-positive campaign called “Just Sex,” promoted by the San Francisco art collective Boy With Arms Akimbo. [See below.] The crowd turned hostile and began to chant, “What’s the charge?” After clashing with police, eight additional students and activists were taken into custody. When an apology from President Benno Schmidt and Secretary Sheila Wellington fell short, 300 students and activists marched on the New Haven police headquarters. The next night, a crowd gathered outside Woodbridge Hall to protest Schmidt’s position by dancing to Madonna’s “Express Yourself.”

Left: Poster by Boy with Arms Akimbo Right: Poster for demonstration against the University’s response to the arrest of Bill Dobbs and others On November 29, 1990, Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Bush administration, gave a speech at Yale where he implored Americans to avoid harmful activities like smoking and driving while drunk. His speech was interrupted by jeers from a group of students and ACT UP activists who had come to New Haven for the speech to protest the administration’s inadequate response to the AIDS epidemic. The University administration came down hard on the student protesters, arguing they had violated Sullivan’s freedom of speech by not allowing him to complete his talk. Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Director of Graduate Studies in the Graphic Design Department at the Yale School of Art, recalls receiving a letter from President Schmidt, instructing her to discipline an art student who had taken part in the protest. She refused, arguing that the pertinent principle here was not freedom of speech, but rather “economy of speech”—the Bush administration got to speak all the time, whereas the voices of student protesters were routinely stifled. AIDS was very much on the radar of the city of New Haven. According to Elaine O’Keefe, Executive Director of Yale’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA), who worked in the New Haven Health Department when AIDS hit, the early years of the epidemic were harrowing. In the beginning, O’Keefe and her colleagues were primarily concerned with gaining a better understanding of what was causing the disease. Nationally, the disease seemed to be having the biggest impact on gay men, and in Connecticut, too, gay men were the most visible figures sounding the alarm about the disease. But it soon became clear that other populations were being affected, especially drug users. Then as now, New Haven’s intravenous drug users were often poor and had meager access to health care. “We really had to move as fast as we could on so many fronts,” O’Keefe says. “Most of these people were dying within a year of being diagnosed.” In 1985, along with Novick and others, O’Keefe started pressuring New Haven’s mayor, organizing what eventually would become the Mayor’s Task Force on AIDS. The Task Force consisted of a number of committees, including an education committee charged with spreading the word about AIDS among New Haven’s various communities, and a housing committee, which focused on getting decent homes for people struggling with AIDS. Working with highly marginalized populations—gay men, sex workers, injection drug users and the incarcerated—presented O’Keefe and her colleagues with daunting challenges. Though the city’s Department of Public Health had some history of providing sexual health services to gay men, it didn’t have organized programs for reaching out to the city’s most disadvantaged residents. As in other cities, public ignorance undermined O’Keefe’s work. AIDS patients in New Haven often faced ignorant hospital staff and healthcare providers who lacked basic information about AIDS and were afraid of contracting it through casual contact. “There was a paucity of providers who were involved in AIDS care,” says O’Keefe. “It really should not have been so difficult.” In the 1980s, the University had only limited involvement in the city’s AIDS efforts. What little collaboration there was came mostly from Novick, who was often frustrated by his Yale colleagues’ lack of support in encouraging the University to steer its resources towards helping to fight the epidemic.

Posters distributed by the Women’s AIDS Coalition of the New Haven Mayor’s Taskforce in AIDS, 1988 One area where the University provided crucial collaboration was in developing needle exchange. Intravenous drug users acquire HIV through blood in syringes that are reused by different people. Needle exchanges—harm-reduction programs designed to reduce needle sharing among drug users and to curb the spread of the virus by providing clean needles—had already been tested in Europe in the early eighties to quell the spread of Hepatitis B. In the United States, though, political hostility to drug-users made them taboo in most jurisdictions. In many states, including Connecticut and New York, merely possessing a syringe without a prescription was against the law. As a consequence, early needle exchanges in the Northeast were illegal, underground affairs. The first person to experiment with needle exchange in New Haven was a former medical student named Jon Parker MED ‘85 SPH ‘92. Parker, a recovering heroin addict and ex-convict from Boston, would purchase needles in Vermont, where there were no restrictions, and transport them down the East Coast in a van, making stops in Boston, New Haven, and New York. Along the way, he would park his van in neighborhoods with high concentrations of drug users and exchange his own clean needles for dirty ones. Kaveh Khoshnood SPH ‘89 PhD ‘95, now an associate professor of epidemiology at Yale’s School of Public Health, remembers reading a riveting profile of Parker in the New Haven Advocate. Khoshnood recalls thinking, “This is why I came to public health. This is bold. Let’s not give drug users a sermon; let’s give them what they need.” Khoshnood grew up in Iran but left in 1982 to avoid being drafted for the Iran-Iraq war. He came to public health with a political, reformist bent. When he arrived at the public health school in 1987, AIDS aroused surprisingly little interest among people working in public health. “We didn’t even have a class on HIV until the early nineties, and even then it was taught by a PhD student, not a professor.” Khoshnood connected with Parker through mutual friends at AIDS Project New Haven, where Khoshnood was volunteering in community outreach. At first, Khoshnood worked with Parker in secret—engaging in illegal activity could have endangered his visa. In the late eighties, as the proportion of AIDS diagnoses linked to gay men sank, the proportion linked to intravenous drug users grew. This posed a challenge for public health workers. While community outreach among homosexuals had had some success in shifting sexual behaviors and promoting condom use, few tools existed for protecting drug-users. According to Gerald Friedland, an AIDS doctor at Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven was one of only fifteen cities in the US where HIV/AIDS had become the leading cause of death among young men and women. “The disease was highly stigmatized,” says Friedland, “especially among New Haven women, many of whom were very isolated due to their drug use and lack of access to healthcare. A lot of babies were also born with HIV, and many were abandoned by drug-taking mothers.” As the epidemic among drug users, their sexual partners, and, ultimately, their children worsened, needle exchange began to attract more interest from scholars and people in government. But politically, needle exchange faced vociferous opposition. New York City established a needle exchange in 1988 through an emergency decree from the health commissioner, but it was hampered by restrictions. When David Dinkins became mayor in 1990, he cancelled the city’s needle exchange programs, arguing that “giving needles to addicts does nothing to stop drug use and in fact promotes it.” In New Haven, too, Mayor John Daniels was skeptical. But after Novick took him on a tour of the neonatal intensive care unit at Yale-New Haven Hospital to see all the AIDS-infected babies, Daniels switched his position. In 1990, after a year of intense lobbying, a team at Yale including Khoshnood, Robert Heimer, a professor of pharmacology, Ed Cadman, head of internal medicine at Yale-New Haven, and Ed Kaplan, a professor at the School of Management, secured funding and legal authorization to conduct a study on the efficacy of needle exchange. A crucial innovation in the study’s design was to analyze actual needles rather than information from drug users, many of whom refused to participate in a study that included rigorous questionnaires. The team’s results were unambiguous: needle exchange worked. New infections among drug users were reduced by 33%. Another finding of the study explained why: When the program began, 92% of the syringes collected from New Haven shooting galleries tested positive for HIV. When the Yale team published its research, it helped make the case for needle exchange programs around the world. Though still controversial in many countries, needle exchanges have been implemented with success in countries as different as Australia and China. In the United States, however, a long-standing congressional ban on federal funding for needle exchange has prevented the strategy from being implemented on a mass scale. (Backed by President Obama, Congress lifted the ban in 2009, but in early 2012 Republicans successfully engineered its reinstatement.) The city’s efforts were complemented by New Haven’s unusually strong network of AIDS service organizations. The largest, AIDS Project New Haven, was founded in 1983 by Novick, Sabella, and eighteen other men and women. Novick and Sabella targeted outreach to gay men at Partners Café and at The Pub, New Haven’s other gay bar, and invited Yale University intellectuals and professionals to govern the board. Even so, the organization’s initial proposals were denied funding by local grant-giving organizations such as the New Haven Foundation, which questioned both the significance of the AIDS epidemic and the ability of a non-medical service-based organization to help fight the disease. As AIDS incidence increased in minority and drug-user populations, other AIDS service organizations sprang up to serve their need. In 1987, a separate organization, the AIDS Interfaith Network, took root when Yale Divinity student Alison Moore DIV ‘90 encouraged a retired schoolteacher named Elsie Cofield to address the epidemic in New Haven’s African-American community. Cofield was the wife of a Baptist minister known for his openness to congregants suffering from AIDS. She began providing services in the basement of her husband’s church. The center grew into a twenty-one-room facility, where Cofield and her thirty staff provided treatment for HIV/AIDS clients, and added programs such as case management, substance abuse counseling, and a teen hot line. New Haven’s third major AIDS service organization, Hispanos Unidos, was also founded in 1987 by Dominick Maldonado and Sher Horosko, two members of the Mayor’s Task Force on AIDS who recognized the urgent need to deliver HIV/AIDS education to New Haven’s Spanish-speaking community. Since its founding, it has expanded its scope to include substance abuse and mental health care. As the eighties wore on, AIDS and safer sex became standard, if controversial, parts of campus discourse. Although there was general agreement among University health officials that students needed access to condoms, distribution incited a backlash. In the late eighties, some college masters decided to install condom vending machines in their residential colleges. Shortly after installation, though, the machines were vandalized. Then, during reunions, a group of alumni complained about the impropriety of distributing sex paraphernalia in Yale’s hallowed halls. The machines were removed. Although many students graduated from Yale ignorant of the impact of AIDS on the University, throughout the late eighties and nineties, many Yale students and staff contracted HIV. As was the case elsewhere in New Haven, it could be difficult to find doctors willing to treat them, at least in the early years. James Perlotto ‘78 remembers that when he came back to Yale in 1988 to work for Student Health Services, he became the de facto AIDS doctor. Although Perlotto was a family physician rather than an infectious disease specialist, he was openly gay, and AIDS was a fact of life for him in a way it never would be for most other Yale doctors. By the time Perlotto returned to Yale, he had already cared for friends who succumbed to the disease. Also, there were few openly gay doctors at this time, and physicians who weren’t comfortable with homosexuality often failed to give specific safer sex advice to their gay patients, or openly disapproved of what many medical professionals still felt was an immoral “lifestyle.” Perlotto, who has treated virtually every Yale student with HIV patient since 1988, recalls how anguished treatment was in his first years back at the University. Although the FDA had approved the first major antiretroviral, AZT, in 1987, the drug by itself did not delay death. Single drugs, researchers soon discovered, didn’t work because the virus quickly mutated into drug-resistant strains; to prevent that, drugs that attacked the virus in different ways needed to be combined. It wasn’t until protease inhibitors were developed in the mid-nineties that drug cocktails became potent enough to transform the disease from a death sentence to something chronic and treatable. John Geter was an emblematic case. Geter had performed on Broadway before eventually deciding to leave the theater world and pursue a Master’s of Divinity at Yale. After Yale, Geter became a pastor on Long Island at a United Church of Christ. Geter was HIV positive, and when he became ill, he revealed his status to his congregation. Half of the congregation voted to oust him. Geter came back to Yale and enrolled in a PhD program. But by this time he was running out of drug options. In the early nineties, Geter had tried AZT as well as d4T. Next, he participated in a clinical trial that gave him access to protease inhibitors. Like many people who had privileged access to drugs, Geter shared them with three desperate friends who were also ill, forcing him to take a lower dose than directed. As a result, the drug did little to retard the development of the disease but allowed his virus to build up resistance to protease inhibitors. Geter tried everything—at his peak, he was taking sixty-four pills per day—but the illness caught up with him. Geter died at University Health Services in 1999. By the late nineties, campus interest in AIDS sagged, just as it did across the country. Although AIDS deaths continued to mount, new treatments seemed to sap some of the urgency from the epidemic. In recent years, though, AIDS activism on campus has once again surged. The focus this time, however, is different. For a rising generation of Yale grads, AIDS isn’t simply an American problem—it’s a global problem. Although the American epidemic rages on, especially among the urban poor, the developing world is now the main theater of AIDS activity. Whereas AIDS activism at Yale and in New Haven was once extremely local, fighting AIDS is now a kind of internationalism. Many Yale students today don’t realize that the disease was originally thought of as a plague among American homosexuals. On October 30, 2010, thirty students from Yale and Harvard interrupted a rally for President Barack Obama by unfurling banners and chanting in unison, “Fund Global AIDS.” Two weeks later, a group of students protested at a talk given by White House Health Advisor Ezekiel Emanuel, brother of Rahm, who was said to have recommended a cut in funding for global AIDS initiatives. When the President released his final budget request in early 2011, AIDS funding was spared.

Harvard and Yale students interrupt a rally for President Barack Obama to advocate for AIDS research funding, October 30, 2010. Photograph by Victor Kang; courtesy Yale Daily News As a social cause, AIDS is more visible on Yale’s campus than ever before. Although the global epidemic is close to the concerns of student activists, in another sense it is remote from Yale’s campus. As the years go by, fewer and fewer students are personally acquainted with anyone who is HIV positive, much less someone who has died from the disease. As AIDS enters its fourth decade, it has been a gay disease and a straight disease; a man’s disease and a woman’s disease; a disease in America and a disease in Africa; a disease of the young and a disease of the elderly; a prostitute’s disease and a banker’s disease; a disease of the homeless; a disease of the famous; a disease of the remembered; a disease of the forgotten. From its first days, it has also been a Yale disease.

— Chris Glazek ’07

PDF verion

Print / Save as PDF

|

An AIDS Memorial.

|

On HIV, Don’t Repeat HistoryYAMP volunteer staffPublished April 23, 2013 in the Yale Daily News Gay men of the Gay Ivy: We are a generation that’s come of age in the wake of half a million Americans lost to AIDS. Since that devastation, what was once a certain death is now a manageable disease. We are a generation that knows HIV, and we know how to protect our partners and ourselves. Despite this hard-won knowledge, HIV transmissions among men who have sex with men, or MSM, are on the rise after years of decline. and now comprise the majority of new infections. Almost half of college-aged gay men will be HIV+ by age 40. For black MSM, the number jumps to 57 percent. While these numbers are startling on their own, what sounds the alarm is that we’ve seen them before. In San Francisco. 20 years ago. History is repeating itself. To reconcile these statistics with the current state of HIV prevention and education, a group of about 30 Yale undergraduates, graduate students, alumni, faculty and local activists met this month. The workshop revealed that those spared the early, darkest years of the plague also missed the critical lessons that succeeded in slowing its spread. Questions that once protected a man’s health have become part of an online hookup culture, flattening once-valid concerns into cheap phrases that no longer bear the urgency under which they were initially created. On apps like Grindr and websites like Manhunt, men post profiles complete with their status, most recent test date and acronyms like “DDF” and “neg UB2.” People ask, “Are you clean?” Degrading language aside, serosorting — when HIV- men only partner with HIV- men, and HIV+ with HIV+ — doesn’t really make sense. A negative test result is not a license to have unprotected sex. A gap of months separates the time you are infected with HIV from the time a test will reveal you are positive. In this gap, your viral load is greatest, which means you are more likely to infect others. Any protective effect of having unprotected sex with negative partners is cancelled out by this potential, untestable increased virality. Safeguards exist to prevent possible exposure. Yale students seem generally unaware of PEP and PrEP: post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis, respectively. The former, if administered soon after exposure to the virus, can dramatically lower the likelihood infection. The latter, if taken daily before exposure to the virus, will do the same. But attributing this rise in transmission to just misguided health choices misses a deeper issue. To paraphrase art historian Douglas Crimp, a chronic illness is abstract until it’s not. As young people, the reality of living with HIV — the regimen of daily medications, their side effects, and frequent doctor visits — is far beyond our imagination. Culturally, the conversation has deviated from the health crisis as well. The Gay Rights movement, galvanized by AIDS, has turned to assimilationist advocacy for gay marriage, relegating mortal crises as secondary. Placing HIV transmission alongside other epidemics facing our community — the violence and victimization of gay men, the burden of depression and heavy use of alcohol and other drugs — it is no surprise that young gay men, already four times more likely to commit suicide than their heterosexual peers, might value and protect their bodies less. To address the crisis of rising HIV transmission, we need to make these social and mental health issues as important and visible as the push for marriage rights. Silence, violence and stigma that feed this shame and misinformation are reproduced at all levels of public and private life, but schools and universities should be the exception. “Light and truth” should be an imperative, not a motto. Yale must foster open discussion and remove all barriers to quick and easy testing for HIV and other STIs. Half of Yale’s gay male students are in peril, and Yale has taken no apparent action to specifically focus on HIV. We must share knowledge and reject historical amnesia. We must speak frankly about sex before, during and after. Assume everyone you sleep with is HIV-positive, use a condom, and explore nonpenetrative sexual practices. Our hope lies in our rejection of the statistical fate that awaits us should we choose to do nothing.

— YAMP volunteer staff

PDF verion

Print / Save as PDF

|