I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

Mark Dallas Butler was a budding scholar of art history when he died of AIDS on January 6, 1993, mere months before completing his doctorate in Art History at the University of Pennsylvania. He was 31 years old.

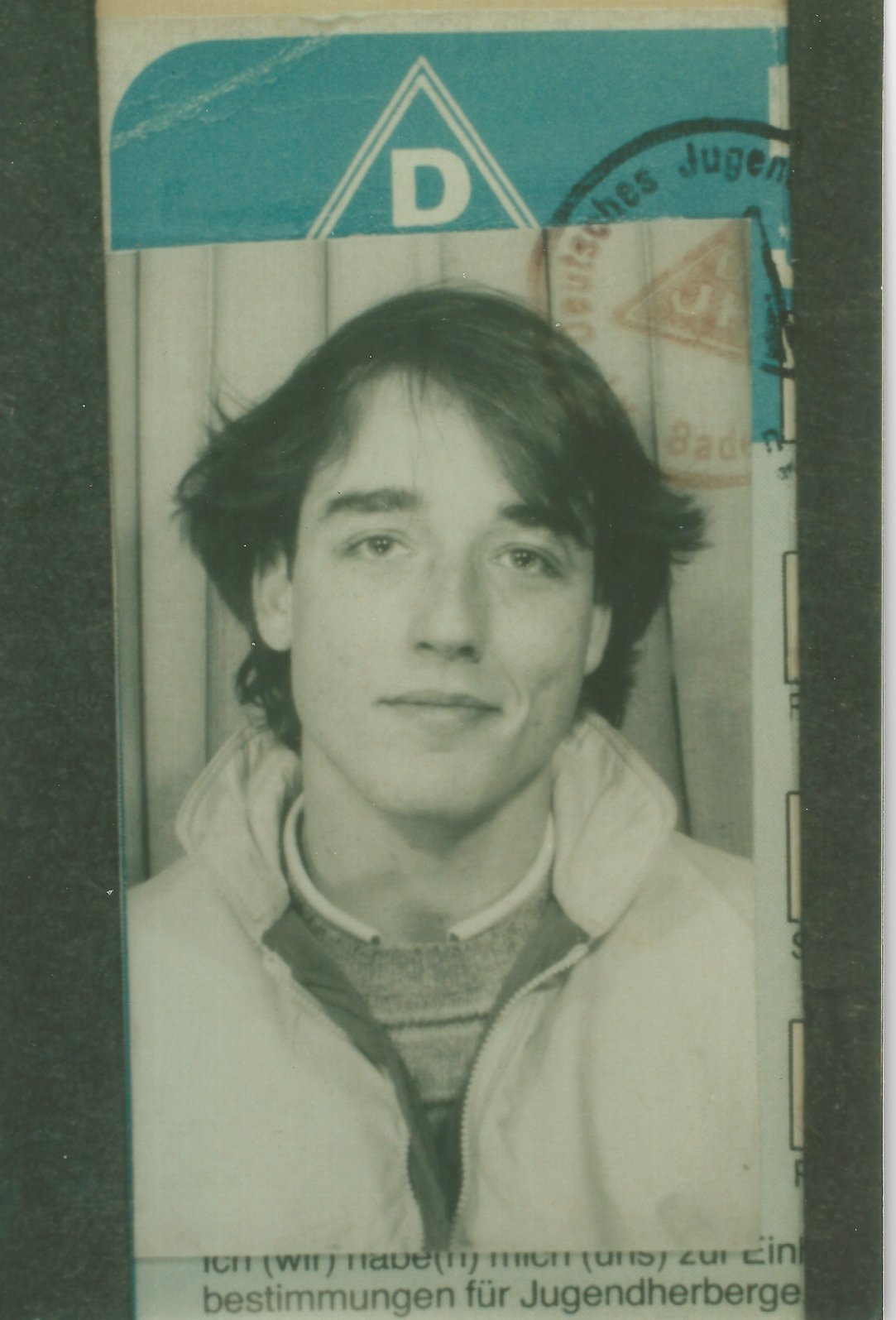

Ten years earlier, he had graduated from Yale, also in art history.

At Yale, Mark lived in Pierson College. He studied abroad in Heidelberg and had a boyfriend in his year, Donald Suggs ’83. Mark was born in Pittsburgh grew up in on the Eastern Shore of Maryland with three siblings in a conservative household where his father was a Methodist preacher. When he left New Haven, he moved back to Chesapeake Bay. He lived in Washington and took a job at the Library of Congress, then at the National Museum of American Art. With such passion for art and culture, it wasn’t long until his his sights set on New York.

In 1985, Mark got a job in the registrar’s office at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum and moved into an apartment with some friends in Astoria, Queens. Once in New York, he immediately took to the parties and romance of the metropolis.

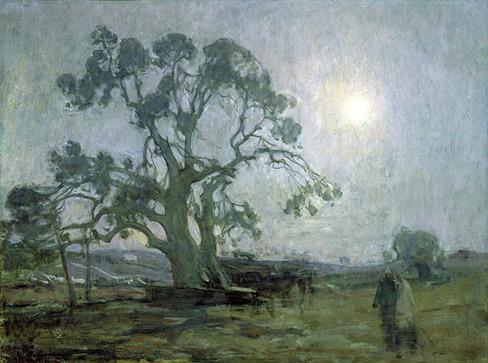

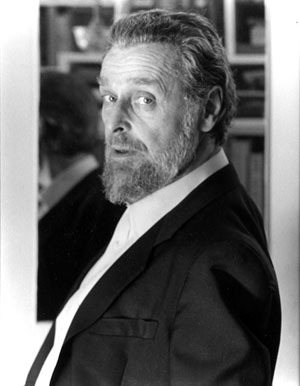

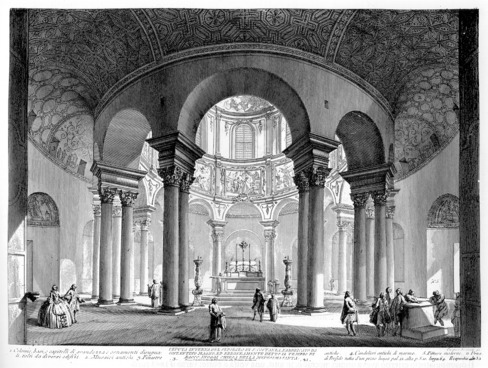

In the fall of 1987, he entered the Ph.D. program in Art History in Philadelphia at Penn, where studied a wide range of topics: from Piranesi to 19th Century Islamic Art. In 1990, was research assistant to Leo Steinberg. In the same year, he coordinated a Henry Ossawa Tanner retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

For Mark, the disease moved slow, and then fast. After receiving his diagnosis in 1989, friends recall he didn’t show significant signs of weakening health until the winter of ’92. His death in the next few months came as a shock to all, but no surprise.

III.

The Mark we knew was very much from Crisfield, a town on the far reaches of Maryland’s Eastern Shore where a four-lane highway halts at the Chesapeake Bay. Crisfield hosts the Miss Crustacean Beauty Contest and the annual Hard Crab Derby. “We bronze the winners,” Mark would say, eyebrows alight, “but we eat the losers.”

At 15, Mark showed up at a summer arts camp in western Maryland. He was quick, flirtatious, fun. (That winter, he tore through the National Gallery of Art, counting the arrows in the St. Sebastians.) The summer before he started Yale, his dad, a Methodist minister, was transferred to a church in our town, two hours up the Shore from Crisfield. Mark, uprooted and irrepressible, landed on our doorstep.

He charmed our mom with his manners, wicked humor, and a fluid way behind the wheel. Soon we were out with him at all hours, pacing the back roads by bike or in an aging Volvo. When he cycled, Mark wove back and forth across the hot pavement, serenading the corn and soy fields with Supertramp’s “Take the Long Way Home.”

By day, we lazed on docks along the river, Mark slathered with a mix of baby oil and iodine (“If the oil don’t fry you, the iodine’ll dye you.”). That first summer he read Buddenbrooks while he tanned, and The Arms of Krupp. Later it was Christa Wolf’s Cassandra.

At night, we drank on Tallulah Bankhead’s grave in an old churchyard south of town. Mark could never find her stone, so he’d start by calling to her as he skipped around the parking lot, his cigarette conversing with the fireflies. Later, walking back to the car through the damp dark, Mark might be fearless amid the hulking boxwoods and looming oaks — or he’d shiver with delighted panic and clutch whichever of us he had at hand.

We weren’t the only ones who’d ever left the Shore in search of art and ideas, but it could feel that way. Mark parachuted merrily from one world to the next, New Wave mix tape frequently in hand. At a crab feast, he posed with our mom in Surf Moscow swim trunks, Lenin emblazoned on the seat. He souped up his Astoria apartment with gold leaf. From Europe, he sent a postcard of the Hotel Angst (“Angst should be at least surrounded by terra cotta, bad Sodoma paintings and Versace linen pants. Nicht?”).

When we shivered, Mark might materialize to play Monopoly or rub a warmed afghan on our frozen toes. After a bad breakup he’d show up at any hour, his long frame quivering with hurt and wry laughter. He brought guys home to meet our mom. Maybe he was practicing; he came out to his mother just before she died.

Mark delighted in the names of tiny places in our corner of the world: Secretary, Painter, Unicorn. We buried him beside his mother, near Exmore and Bird’s Nest, an hour south of Crisfield, where Maryland gives way to a thin slip of Virginia. The road down the Shore stretched even beyond our memory of it, a light snow muting the pavement and the winter fields and creeks. Our mother drove, gripping the wheel hard the whole way.

From an apartment on Howe Street, my girlfriend and I watched the roof blow off a garage. The winds of Hurricane Gloria shook New Haven. I’d just finished my M.A. and moved back to New Haven after a summer spilt between Sofia, Bulgaria and New York, where I could not find a job. The phone rang. Mark’s voice crowed over the wires.

“I’m moving to New York,” he said.

“When?” I asked.

“Now,” he replied. He was on the road from D.C., calling from a pay phone. “I have an apartment in Queens, in Astoria. Come and be my roommate.” He’d also landed a job in the registrar’s office at the Cooper-Hewitt.

“Um,” I said, unable to make a quick decision and worried about him driving in the weather.

Less than a year later, I moved to Manhattan. After a few months in the meatpacking district, and many nights on Mark’s couch, I got my own apartment in Astoria. Weekday mornings, Mark met me at my car. I often found him at the curb, swilling coffee and dancing in place. I drove us over the 59th Street Bridge. We sang along with the radio, chatted, popped tapes in and out of the car’s balky cassette deck. Mark always waved, shouted “Good morning” to the officer directing traffic at the foot of the bridge. Evenings we often had dinner at his place, and sometimes we got gussied up and went out. Of course, Mark dressed me and fixed my cowlicky hair.

It was probably 1987; we attended a junior associates party at the Cooper-Hewitt. As an employee, Mark was invited to events at the museum, and he delighted in opportunities to show his friends around the galleries and back rooms. This party was held in the garden, under a huge tent, in the pouring rain. Mario Buatta, the interior designer known as the Prince of Chintz, had festooned every pole and wire with his signature fabric. Mark looked tall and dapper in his slim, gray suit. I wore an A-line black velvet cocktail dress that we’d picked up at Barney’s warehouse sale. We entered the tent, me on Mark’s arm, and paused, surveying the scene—bi-colored bubble dresses and champagne flutes, high heels sinking into the rain-softened turf, a table of elegant ladies immediately to our left. We sailed forth, toward the bar.

“What a handsome couple,” one of the elegant ladies exclaimed. Mark squeezed my arm. When we reached the bar, he leaned down and whispered, “That was Brooke Astor.”

We toasted each other, and settled into our own corner, with our own bottle of Veuve Clicquot. The rain intensified. Guests trickled away.

When my relationship broke up, Mark looked after me, including me in holiday plans and taking me along on vacations. On a number of occasions, we drove to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where his father lived and where Mark had grown up. Cruising around in my red Toyota, we admired white-painted houses, screened-in porches, and meticulously trimmed boxwood hedges. We made a pledge; if we were both single by the time we turned forty, we would marry each other, move to the Eastern Shore, create a home.

When Mark spotted a house he particularly liked, he flung his arms in the air and shouted “Tara!” This was a house we could live in. As of this writing, I am fifty-two and single. Whenever I spy an inviting cottage or enticing flat, traveling through the countryside or on a stroll in Manhattan, I hear him calling, “Tara! Tara!”

Tim Dlugos wrote this poem in New York on July 7, 1983. In draft, the poem was dedicated to Mark Butler. From A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos, edited by David Trinidad (Nightboat Books, 2011). Used by permission of the Estate of Tim Dlugos

I met Mark the summer after what had been our freshman year in college, his at Yale and mine at Penn. It was 1980. We worked together as counselors at a summer program for gifted high-schoolers. Most of the girls in the summer program were in love with Mark, as were many of the boys. They would tag along with him until he told them, in his perfect dead-pan voice: “go away.”

My memories of our escapades outside of work tend to blur together – I don’t remember which year it was we took off for the Eastern Shore, crashed at the James’ family home, drove to his favorite secret places, along the Chester river. I do remember being on the dock at Gratitude Landing in Rock Hall on the night of the royal wedding, seeing a pair of swans swim together in the inky black waters, and watching Mark point out that in Art, swans were a symbol of royalty. He always made the perfect connection.

Mark and I became fast friends after that–he was lively, intelligent, fun, charismatic. I was impressed by his openness about being gay. At Yale, Mark dated classmate Donald Suggs ’84 and I remember when he brought Donald to his conservative parents’ house for the holidays. I always thought that must have taken real guts.

Throughout college, when Penn played football games at Yale, I would visit Mark, avoiding the football crowds altogether. It was then he took me to one of the college’s first gay dances.

After college, when Mark moved to New York, I visited him there, too. I remember when he took me to the storage rooms at the Cooper-Hewitt Musuem where he worked. I have a Polaroid of him wearing a delicate feathered hat from the museum’s collection that had once been the Queen of England’s.

At that time he lived in Astoria, Queens with a coterie of close friends. He always wanted me to move to The City. We had fun times during those visits: cocktail parties with young museum professionals in Midtown, bar-hopping downtown (Boy Bar, Uncle Charlie’s, the Pyramid Club – this was the 80s). Astoria, however, was hardly gay-friendly – but Mark said he’d never been gay-bashed; at most, some kids had once taunted him in Central Park: “Pee-wee Herman! Pee-wee Herman!” But he was just trim. And dressed in a suit.

At the time of his diagnosis, Mark was in the Ph.D. program in art history at Penn, writing his dissertation on illuminated manuscripts. When I finally got the chance to fly to Philadelphia and see him, I remember we got a hotel room at the downtown Holiday Inn–and spent a weekend catching up, telling stories, watching figure-skating on TV.

Mark’s decline in health was pretty swift. When I left him in Philadelphia, I knew it would be the last time I’d see him. If he were alive today, I think he would be an important museum director. He had the intelligence, discipline, creative spark, courage, initiative, and charisma to go to the very top of his field. And he would have had legions of friends cheering him on.