I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

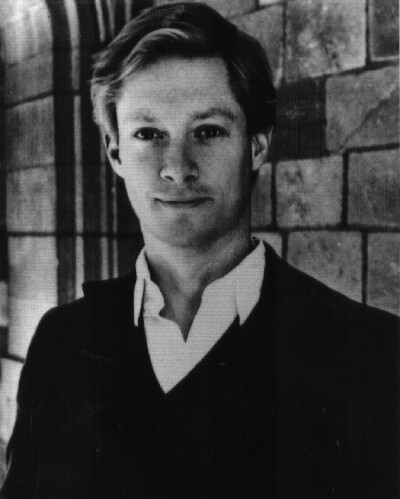

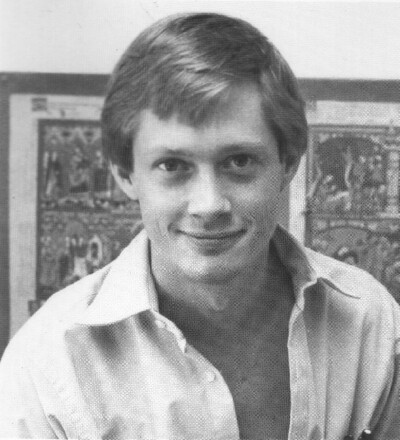

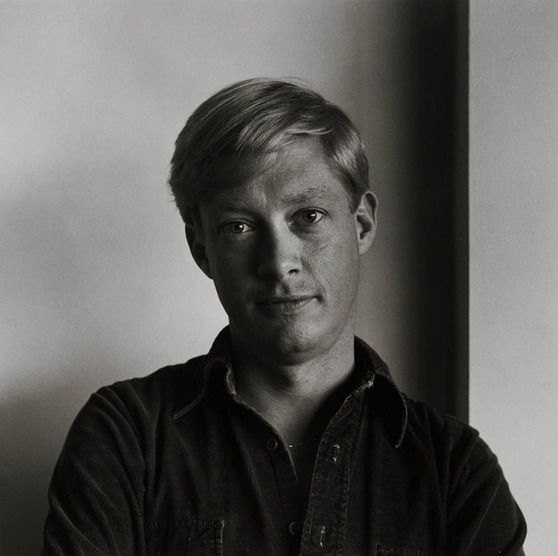

John Eastburn Boswell (known by friends as “Jeb”) was one of the world’s foremost scholars on the history of religion and homosexuality. Born in 1947 to a military family, Jeb spent his childhood in Boston, Mass. as an Episcopalian. By the time he finished his undergraduate degree at The College of William and Mary in 1969 in Virginia, Jeb had converted to Roman Catholicism, to which he remained a devoted follower for the rest of his life.

After college, Jeb pursued his doctorate in history at Harvard University in Cambridge. A talented scholar, Jeb utilized his knowledge of 17 languages in his studies, including Ancient Greek, Catalan, Latin, Church Slavonic, Old Icelandic, classical Armenian, Syriac, Persian and Arabic, among others. In addition to his intellectual interests, Jeb was known among peers for playing piano music in his room in the all-male graduate dormitory Conant Hall. He introduced his friends to the world of “Greater Gay Boston,” to which he had been familiarizing himself for years.

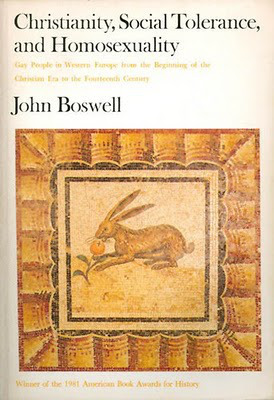

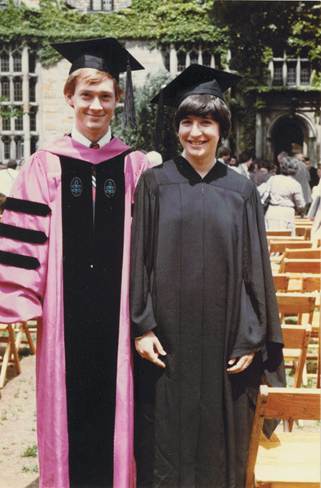

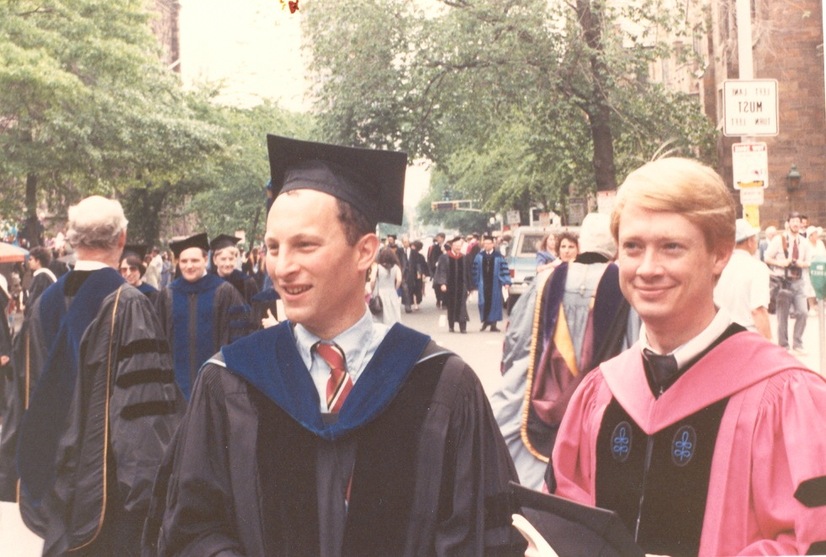

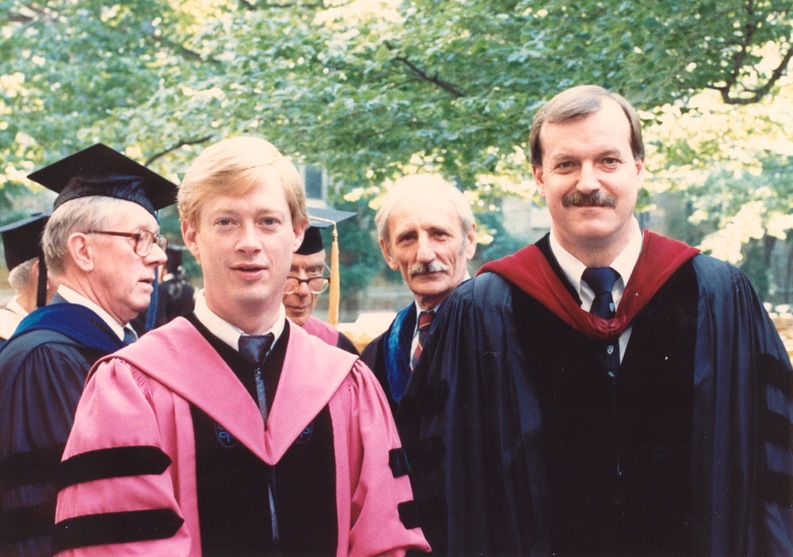

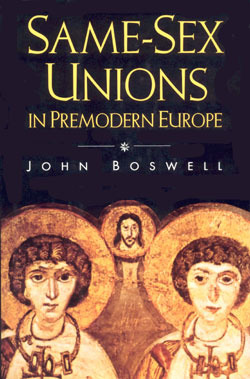

Jeb graduated from Harvard in 1975 and immediately moved to New Haven, taking up a teaching post at Yale. He was made full professor in 1982, and served as the chair of the history department from 1990 to 1992. In 1987 , he helped found the Lesbian and Gay Studies Center at Yale. While at Yale, Jeb published four books, including his 1980 work Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality which garnered much controversy and was described as “revolutionary.” He was also a much-beloved teacher, with many of his undergraduate classes ranking in the top ten for highest enrollment. He took time to mentor students individually, and in some cases, used his wide knowledge of lesser-known languages to translate sources for his students.

Jeb died of AIDS-related complications on Christmas Eve, 1994, surrounded by his partner Jerry Hart, sister Patricia Boswell, and friends Aaron Laushway and Joe Gordon. He was 47.

II.

III.

On Christmas Eve in 1992, we decided to walk to my church for the midnight service—savoring the bracingly cold air and the opportunity to sing carols in harmony as we so loved to do. Jeb was a tenor and I an alto, so one of us always had to make the enormous sacrifice to croak out the melody. Ever since that October, when Jeb had missed our parents’ 50th wedding reunion due to yet another in a long string of exotic illnesses I had been worried. Tonight, I would ask him the question whose answer I dreaded.

The service ended with the passing of a flame from candle to candle among the assembled worshipers. We started home, still alight with the beauty of the service. As we neared my home, I screwed up my courage and said, “I have been wanting to ask you but afraid to. Do you have AIDS?” Jeb stopped and without a word began to weep. I put my arms around him and cried on his shoulder, as we stood in the middle of the road on that cold early Christmas morning. Finally, I asked the most unanswerable of questions, “Why? Why would God do that to someone as loving as you?”

To answer, Jeb reached back across the decades to our childhoods, to C. S. Lewis’ mythical tales of the land of Narnia. Narnia was ruled by a beloved lion. When the first English children were introduced to the country, they heard tales of this lion—Aslan—and inquired about his nature, for he sounded quite ferocious. “Is he tame?” they inquired. “No, he’s not tame, but he’s good,” the beavers answered. And so, Jeb answered me now: “Remember, sweetie, He is not a tame lion.”

Jeb’s love of God was the driving force in his life and the driving passion behind his work. He did not set out to shake up the straight world but rather to include the gay world in the love of Christ… to acquaint all with the fearsome power of that love, the wildness, the “not tameness” of it. When asked just before his death about possible speakers for his funeral service, Jeb requested that either my mother or I deliver his eulogy. “But Jeb,” I argued, “you need someone who can talk about your life’s achievements.” “No,” he responded, “I need someone who can talk about my faith.”

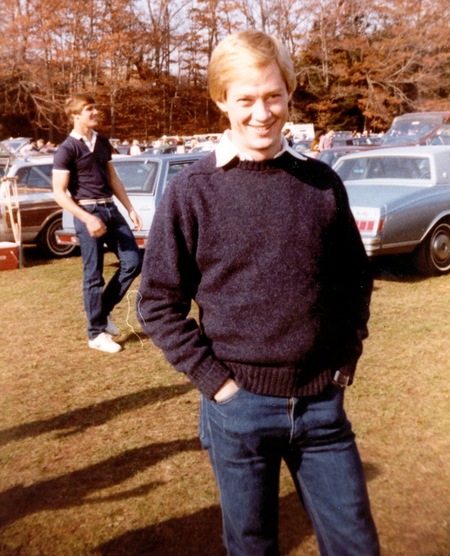

My very first memories of Jeb are entrenched in my mind. His blond hair, blue eyes and sparkling smile attended a personality that was filled with energy, intensity and gregariousness. He was passionate about ideas, obviously well-read and loquacious about his thoughts. I could have said opinionated; but that would be only partially true.

Jeb was opinionated, make little mistake, but he was conversant in just the right way. Disarmingly charming, he would listen to you with intent and care; but it was so true that he was formulating his response to the yet-to-be-known conclusion. He was so very smart. And, he was so very good.

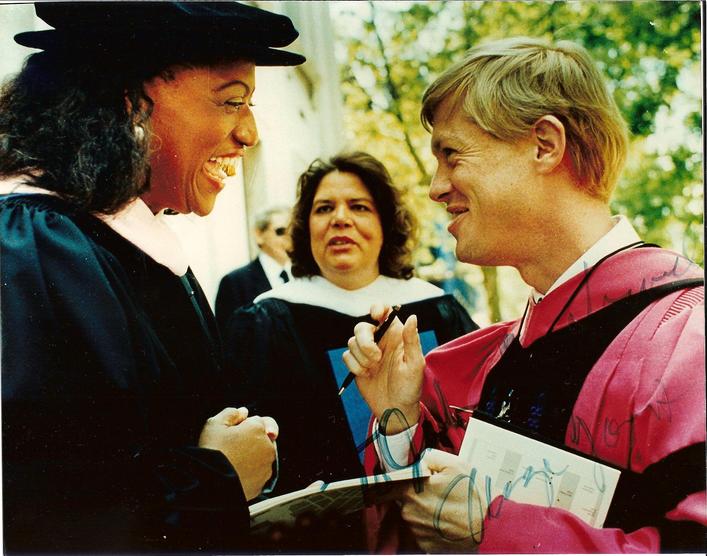

Jeb warmed the spaces around him. His heart was as large as his lanky fame and permeated the environment in which he lived. I was never his student, but I longed to learn from him, and did often enough. He disarmed one with his, at times, child-like charm, but always treating the other with nearly exquisite empathy. So, the pews at his funeral brimmed with all those whose lives he bettered, among them four Yale presidents.

I knew Jeb as a friend and colleague in my work with the Yale community in the late 1980s and early 1990s. I knew him as my parishioner, as well. He was a devout Roman Catholic. After his funeral, his mother told me that when she had learned of his desire to join the Catholic Church, she suggested he wait for a few years so he could make a more informed decision, hoping to hold off this rash move. His immediate response to her, “How long will you deprive me of the Sacrament?” Did I mention that he was disarming? He became a Catholic aged 16.

Jeb was an eminent historian. He spent an exemplary career trying to secure the rightful place of gay men and lesbian women in history, especially in the lives and rituals of their Roman Catholic predecessors. He worked arduously, ably aided by his dear friend, the equally brilliant Ralph Hexter, to finish his book on same-sex unions, which was published the year he entered eternal life. I still have my copy, signed by a wobbly and loving hand in the Yale infirmary.

It was in that infirmary where I sat on the bed next to Jeb’s body with his beloved partner, Jerry Hart, our precious friend, Joe Gordon, and Jeb’s treasured sister, Pat. It was Christmas Eve and Jeb had taken his last breath and we needed to regain ours.

His illness was awful on many levels; his death deprived us of our loving and brilliant Jeb and the world and Academy of a persistent and clairvoyant voice claiming recognition for homosexuals athwart the ages and our rights today.

But this was 1994, and not the Middle Ages, yet Jeb, God bless him, never conceded his HIV condition, at least not to me, and I listened to his sins. With Joe’s ever gentle persistence, I turned to a heart-broken Jerry asking him what would we now say?

Among Jeb’s topmost gifts was endowing others. His mentorship was legendary. His scholarship is meaningfully contributive. He advanced the rigorous study of homosexuality in history, literature, and religion. But, I wager, his legacy to us all is the good and proper use of our natural God–given gifts and persistent work to hone our other talents.

His heart taught us to love and lift up others, urging all to uphold others, urging all to recognize and respect the dignity of each and every human person, constantly, with compassion and charity.

He was a very good Catholic man, who now resides, I so strongly believe, in the beatitude of all virtue and bliss with Almighty God, perfect love.

But, back now to that Christmas Eve in the Yale Infirmary and the question about his passing at such a young age; well, then, what should we say?

Well, we would tell the truth, which may have evaded him and us, but no longer: Jeb died from AIDS-related complications.

If he could not say it – in his strength, his character, and his love – in his death, he enabled us to say so for him.

Lux et veritas.

Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine.

Et lux perpetua luceat ei.

Requiescat in pace.

Amen.

Aaron Laushway

8 September 2012

Birth of the Virgin Mary

Charlottesville, Virginia

Jeb and I had season tickets to the plays at the Long Wharf Theater. Since we had season tickets, we never worried in advance about what play we would be seeing on any given night. One year, on a cold, miserable night at the end of a long week, we found ourselves at the Long Wharf. We opened our programs and discovered that the play was a musical about racial strife in South Africa. We looked at each other and sighed.

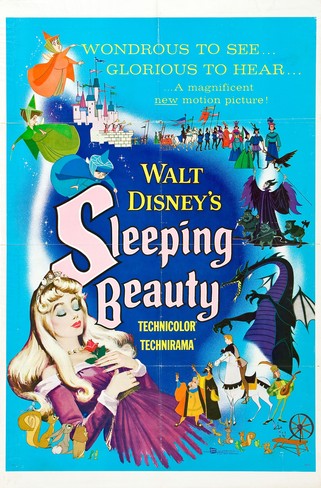

We didn’t need to point out to each other that, of course this was A Very Important Topic, and this was probably A Very Important Play, but it was not what we needed that evening. After a moment, I turned to Jeb and said, “You know, Sleeping Beauty is playing at the Cine 1-2.” Pause. “Oh, we couldn’t,” he replied. Pause. “Oh yes we can,” I said. Pause. The play had not yet started. We put down our programs, walked right out, and drove up I-95 to the movie theater. When we got there, we discovered that were the only two people in the theater. We had a wonderful time. We laughed, we sang along, we enjoyed vintage Disney, we admired the handsome prince, and it was a perfect evening’s entertainment. We heard later that the Long Wharf production was indeed significant, and friends were horrified that we had left, but I wouldn’t have traded that evening for anything.

One of my chief goals when I joined the Yale faculty in 1984 was to meet John Boswell. I had been told by several people that Jeb (as he was called by his friends) was the architect of much of Yale’s social and intellectual interaction for gay men. I hoped that I would be able to join his circle. I was able to meet Jeb when he made an appearance as a guest Professor for a gay studies course being taught by Greg Herek in the Psychology Department. My only recollection of that class is that Jeb was brilliant and that he used the euphemisms “pitcher” and “catcher” with great frequency. After class, I approached Jeb to introduce myself and, almost instantly, I asked a favor. I explained that my (not yet quite ex-) boyfriend was coming to visit New Haven. That boyfriend had admired Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Would Jeb be willing to have dinner with us? As I think back on that moment, I’m unclear why Jeb so readily said yes. We subsequently had dinner at Hunan Wok, where Jeb’s long-term partner, Jerry, also joined us. For much of the next ten years, I had the pleasure of visiting Jeb and Jerry’s home for what might fairly be characterized as their Friday night salon. It isn’t easy to isolate single memories from those many Friday nights. I remember hours of storytelling as well as some very intense debates. There were some flares of anger but mostly abundant good humor.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

Outside those Friday nights, one of my fondest memories is a tiny moment from an anniversary party for Jeb and Jerry that took place at Mory’s. I forget exactly when they got together, but this would have been something like their 20th or 25th anniversary. A group of about ten of us were celebrating in one of Mory’s upstairs rooms. It was a Monday night, so the Whiffenpoofs were in attendance. They chose to serenade us with “Anyone Can Whistle.” The lyric enumerates all the activities that the singer finds unchallenging including, “I can read Greek—easy.” The Whiff who sang those words looked at Jeb and laughed with recognition. I cherish this memory because the moment indicates how completely renowned, admired, and beloved Jeb was among Yale students. It was also so deeply true that Jeb could read Greek—easy. I miss the effortless excitement of his intellect and his enduring generosity.

On a hot afternoon in August 1970 I heard piano music coming from a room in Conant Hall, an all-male graduate dormitory at Harvard. I knocked on the door and the man responsible for the music appeared and introduced himself as Jeb Boswell. We soon became friends, and it wasn’t long before he welcomed me into the world of Greater Gay Boston. Naturally, I am grateful for my Harvard education in my chosen field of historical musicology, a subject for which Jeb shared my passionate interest. Nevertheless, the great legacy of my graduate school days was unquestionably my friendship with Jeb. In addition to our many private conversations which I cherished then and now, I also relished my proud role as the honorary Straight Man who was privy to the brilliant post-Stonewall conversations that emanated from Boswell’s salon.

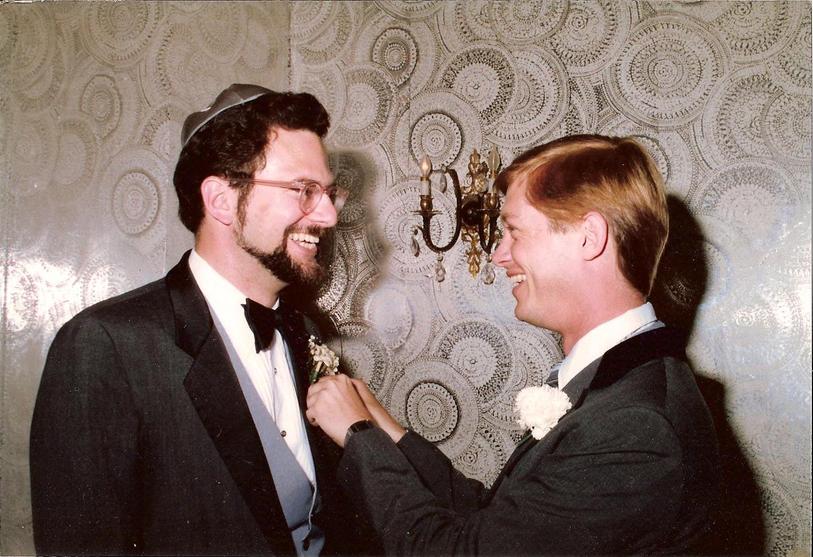

Over the years I met most of Jeb’s family and he met mine. My parents loved him, and one year he even led a Passover Seder in their home in California in my absence. He was the best man at my wedding and stole the show with a moving toast in which he expressed his optimism in the future of my marriage to Jacqueline. Six years later he was Godfather to our first daughter Jessamyn and seven years after that, although deceased, Godfather (in spirit) to our second, Eliza.

Jeb fought passionately and tirelessly for gay equality and acceptance. He would be thrilled to learn that for the past few years he could have married his longtime partner in his home state of Connecticut (he met Jerry not long after we first became friends) and that, as a result of the 2012 election, he could do the same in my home state of Washington. Shortly after this most recent vote I came across a sign on a lawn that would have made Jeb, a devout Catholic—perhaps paradoxically considering this institution’s take on his sexual identity—extremely happy. It simply said, “Approve R-74. My Church Supports Marriage Equality.”

Although once described in print by Gore Vidal as “ferociously scholary,” Jeb was more than the pioneering scholar who had mastered more than a dozen languages and rediscovered the Middle Ages. He may have been the most charismatic and brilliant human many of us have known, but he was also one of the kindest and most generous. In my case, depending on the occasion, he was my best friend, a brother, and a father to me, the person to whom I could turn to assuage the stresses of academic life or the emotional pain brought about by a broken heart. Jeb was the friend with whom I could discuss more of everything and anything on more levels than I could imagine possible before or since. Ironically, the difference in our sexual orientation removed rather than created barriers to love and understanding. In response to the foibles and relationship woes of his straight friends he sometimes joked that, “You straights are so mixed up.” But he cherished people for their individuality, foibles and all, and in his life as well as his work he made the world a more tolerant place for everyone.

After a quarter century, the first years with nearly daily contact and later almost yearly visits, I saw Jeb twice in 1994, his final year of life. When I traveled to see him that winter he had just gone into a coma, and I left Seattle, my family, and students, thinking I was going to be attending his funeral. By some miracle he snapped out of it by the time I arrived to receive friends and family from all over the country. During my week in New Haven I witnessed Jeb once again brilliantly and miraculously holding court from his hospital room at the Yale infirmary, reciting lines from My Cousin Vinny and singing Cause I’m a Blond from Earth Girls Are Easy. While I was there, his father, Colonel Boswell, saluted Jeb’s courage, the newly-installed President of Yale, Richard Levin, cried freely, a devoted graduate student visited daily, people regularly drifted in to thank Jeb for helping them through a crisis, and a young barber who came to the infirmary room to give Jeb a haircut moved us to tears when he refused payment.

We also had some time alone during which he revealed that his biggest worry was that he was leaving me and so many others “in the lurch.” I am deeply grateful I had the opportunity to thank him for what he taught me about the meaning of life, to tell him that I wanted to dedicate my next book to him in his memory, and to say goodbye. When we said our tearful farewells we agreed that it was one of the most joyous weeks either of us ever had. When I saw Jeb for the last time that August, eating was one of his rare pleasures, so I made him and his friends a turkey with all the trimmings. I was too numb to cry much when he died a few months later on Christmas Eve, but I made up for it three weeks later at the birth of Eliza, the first of many occasions when I learned that, although Jeb was gone, he would also remain an inextricable part of me and everyone who knew him.

I was fortunate enough to meet Jeb before he got so famous. We arrived at Yale at the same time, he as an assistant professor, I as a freshman. In the fall of my sophomore year I took a junior seminar with him. In future years it would have been impossible for anyone not a junior to get into one of those seminars—the demand was huge. But this was long before social media, and word just didn’t get around that quickly. There were only about 7 people in the class. The class was on “minority groups in the early Middle Ages,” but it also included women, even though, as he pointed out, women were not a minority. I look back now at the books on medieval women we read that semester, and they were hot off the presses; he was way ahead of the curve. Possibly it was that semester that set me on my career path as a professor of medieval gender history.

But what I remember most about the class wasn’t what we read, but Jeb himself, and the way he taught me to read. Even though I was educated at a good public high school and had taken a lot of US history my freshman year, I had never before encountered anything like the way he could look at something and get levels of meaning from it. One way I benefited from its being a small class, too, was his availability outside of class. I had references to some sources that were available only in Latin. He sat in Machine City and translated them for me. When I thanked him, he just looked at me and said “YOU need to learn Latin.” Next semester, there I was in intensive beginning Latin. At the end of the semester, I was hospitalized for something that turned out to be a false alarm. I wasn’t in much discomfort, but I couldn’t write my paper, so I wrote him a note and had a friend leave it in his mailbox. That afternoon, there was Jeb in my room in DUH. “Just coming to check up on you!” I was still somewhat scared of him, but it meant a huge amount.

Jeb was also, not the first gay person I knew, but the first gay person I was aware I knew (this was 1976, and I wasn’t especially sophisticated). I credit my growing friendship with him with the fact that when my best friend from high school came out to me that fall, I did not react like a total jerk or idiot.

After that semester, I was a confirmed groupie—one of his first. I took another class with him and wrote my senior essay with him. I went off to Oxford for a couple of years, and he and Jerry visited me there. I returned to Yale for graduate school and worked with him again. I am constantly grateful to have had a mentor who was also a good friend, supportive not only of my work but of my life generally. After I left Yale we had many long phone conversations, especially after I started working on the history of sexuality.

Even now I find myself wanting to talk to him about something, and am drawn up short when I remember I can’t. I periodically circle back to his work, recently having occasion to reread parts of Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. I think of him as I try to learn Hebrew, remembering how good he was with languages and how important they were in his scholarship. Jeb was a pioneer in two fields of study that really blossomed in the early twenty-first century, the historical study of sexuality and the study of Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations especially in Iberia. But I remember him mainly as a teacher, and hope I can give my students some of what he gave me.