I.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

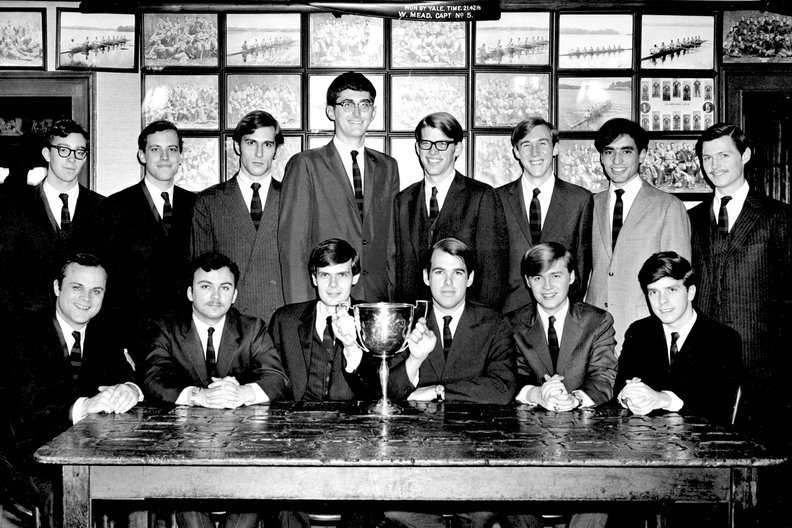

John Anton Tardino, Jr., was born in Merrick, New York, in 1946; He was the youngest of three children. At Yale, he majored in history with an independent concentration in American Studies and sang in the Yale Glee Club, Spizzwinks(?), the Silliman Chorus, the Dwight Hall Tutorial, and the Whiffenpoofs. He was also a member of Book and Snake, a secret society.

Through his many activities at Yale, John moved around the country and the world. In 1966, Spizzwinks(?) went to Venezuela and toured universities and hotels with the help of the U.S. government and Creole Oil. In 1967, he auditioned and was selected to act in a mobile theater program funded by Urban Corps, a federal program to give students summer jobs in New York City. When the Urban Corps director decided his idea was infeasible, Yale students took it over and ran the Mini-Mobile Theater themselves. John helped rally resources from municipal agencies and then built sets onto the project’s sixteen-foot flatbed truck. He became a manager, setting up stages and driving actors to the performances. John was selected in 1968 by the Yale-in-China Association to teach for two years at New Asia College in Hong Kong.

John graduated from the University of Buffalo Medical School in 1974. He entered family medicine, then a new type of medical specialty, and worked at New York City’s Family Care Center.

He was a member of the American Fern Society.

John Tardino died in the early-to-mid 1980s in New York City.

III.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

Hong Kong in the late 1960s felt passionless, bland, somehow exempted from the turmoil that the ‘60’s generated elsewhere, and John felt he’d been been set loose in it without a clear notion of why. We had both won fellowships to spend two years teaching English at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, with the understanding that we would have plenty of free time. But to do what? Across the border from Hong Kong lurked China, then in the throes of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, and the Vietnam war raged five-hundred miles to the south. But most Hong Kong residents had developed a kind of tunnel vision, unconcerned with the war (except when American warships stopped in Hong Kong for R&R), neither pro-China nor pro-Taiwan— about the only thing they were pro- was money.

We studied Chinese, saw lots of movies, played basketball with our students, and John did volunteer work for the colony’s best-known social worker, a woman named Elsie Elliott who was called “the conscience of Hong Kong.” Even so, he didn’t feel entirely engaged. The place was particularly hard on an aspiring artist, which John then was; the colony had little use for the artistic spirit, and John specialized in it. He’d been a Whiffenpoof at Yale, and now he tried sculpture, pottery, drawing. Our students were mostly timid and drab, suggesting to us that their educational system’s relentless emphasis on memorization had extinguished all spunk and curiosity. I suspect many of them didn’t know what to make of John. For starters, he was about as un-Chinese-looking as could be imagined: he was handsomely dark-skinned, with thick strands of black hair that sometimes slipped down over his eyes and an elegant, aquiline nose. He dressed flamboyantly, at least by their prim standards, and encouraged them to break out of their dreary patterns.

In one of the logs we were periodically required to submit to the program’s headquarters in New Haven, John wrote that when an English class he was teaching was going particularly badly—the students were “bored and unresponsive”—he and fellow teacher David Wilson held a party to try to loosen them up:

“The students arrived in small groups and everyone sat around uncomfortably for a while…. Girls on one side of the room, boys on the other… of course. Finally we had something to eat and then sang some folksongs and things became a little more relaxed. Then we decided to put on some records and dance. This was really the critical point because if this failed, the party would have been rather dull and nothing would have been accomplished. We wanted to get through to the students that we were good guys who really wanted to help them and get to know them…. Wilson and I asked a few of the most attractive and therefore less shy girls to dance and they accepted. They then asked others and found no other girls would dance, claiming they didn’t know how—and God knows they don’t know how— but that’s not the important thing about dancing. Dancing is having fun. It’s relaxing and expressing the emotions of the music in a very personal way. People don’t really have to know how to dance… just know how to feel the music.

Well, we taught several of them some simple steps and then got the boys to ask them to dance. At first the girls turned them down, saying they couldn’t dance, but when they saw us standing there with the boys we’d just taught, they cringed a little but got up and danced. This sort of shy and awkward process went on for awhile but soon both boys and girls began to enjoy the dancing. It was no longer a trial for them to get up and dance. The girls no longer looked away, hoping not to be asked, when a boy walked up to them…. Some even began imitating their American teachers, and one of my more flamboyant performances was a giggling success. A party that might have ended in disaster at ten o’clock had lasted until twelve, and only ended because students had class the next day…. By the end of the evening the students and teachers were friends. We had talked to them about many things, some personal, some to do with school. But they were no longer afraid to talk to us. They saw we were interested and they responded. All very simple and very wonderful.”

I didn’t attend that party, but I can easily imagine John there, finding a way to charm the regimentation out of his students. Every one of them is wearing a white, short-sleeved dress shirt, while John is full of color. Wrapped elegantly around his neck is a long scarf, which flutters behind him as he dances.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

John Tardino had a beautiful tenor voice, and he was a key soloist in both the Yale Spizzwinks(?) (1966-67) and Yale Whiffenpoofs (1967-1968). I served as pitchpipe of both groups, and would often start our performances with one of John’s solos. His voice was crystal clear, always on pitch, and with perfect timing, as can be heard in his solos on Delia and Slap That Bass; John also had a magnetic personality and a sparkle in his eye that charmed all the females in the audience. John had a magnetic personality and a sparkle in his eye that charmed all the females in the audience. We all hoped our dates would not be so distracted by him that they would drop us from further consideration. We were living at a time in history when many gay people simply kept their preferences private.

John had a great sense of humor, and his antics would often create a minor measure of havoc in our performances that the audience enjoyed watching but which I sometimes found frustrating. It was, after all, my job to get people to sing well. It is hard to accomplish that goal with John making snide remarks or telling jokes and getting those near him to laugh instead of sing! His sense of humor was often sufficiently powerful to distract half the group. When we sang well, John was usually a key part of the sound. When we sang poorly, John was often a key part of the problem. John was never boring.

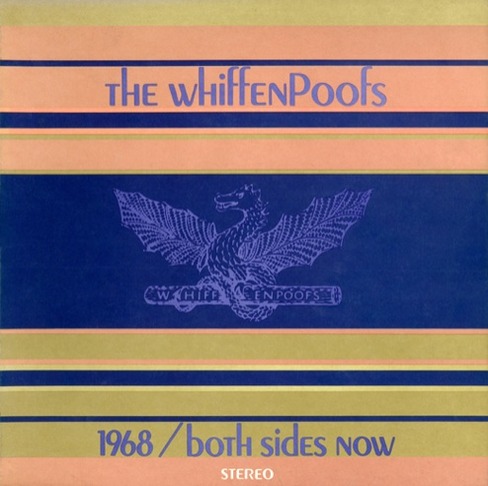

John was also a creative graphic designer. I remember visiting him in his dorm room while he was designing the cover for the 1968 Whiff album. He had a myriad of different colored slices of paper that he would arrange in various combinations, show them to me and ask “what do you think?” When I responded something along the lines of “much too subtle, add some brighter colors,” he quietly told me that further input from me was neither needed nor desired. He then added that I should “stick to the music.”

John was also an anti-war activist convinced, like most of our class that the Vietnam war was a morally corrupt endeavor, not to mention a really stupid idea. When I mentioned to the Whiffs that my draft number was 13, John immediately pulled me aside and recommended Canada. He did not want any of his friends to go into the military, and would actively argue for alternatives to service. I rarely missed an antiwar march because John would make sure I attended. At the same time, he would laugh as we marched, suggesting this was all a “complete waste of our time.” When President Brewster asked us to sing for Lady Bird Johnson, John refused to sing because he assumed any performance would be viewed as our endorsement of the war. Although I was able to get him into the room, he hid behind one of the dividers until one of us pulled him back into the room. He agreed to stand with the group, but not sing. Needless to say, my suggestion that he sing “Slap That Bass” was dead in the water.

John was a great singer, a man of principle, and a fun person to be around. He was a student of life with a unique perspective.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

I remember Tap Night 1967, when both John and I were tapped into the Whiffenpoofs. After drinking the traditional swig from each tapping Whiff’s gallon jug of alcoholic brew (which ensured almost immediate inebriation), we both took notice of an attractive girl dressed in a yellow, strapless gown who was actively engaged in singing every Whiff song we knew. We were puzzled and intrigued —although she seemed completely familiar with all the Whiff arrangements, we did not recognize her as one of the known Whiffenpoof girlfriends (and believe me, the Whiff girlfriends were known to every undergraduate wannabe Whiffenpoof…). We never figured it out that evening. The following morning John took off to Book and Snake’s tomb to nurse his hangover. He returned to our suite in Silliman that afternoon to announce: “I know who that girl was last evening that you found so intriguing.” And as he closely watched my face, he revealed that it was none other than one of the ’67 Whiffs, he of slender body and aquiline features, who had been cross-dressing!! This news put me into the acute tailspin of a male identity crisis, which, of course, amused John to no end! Naturally, I was too self-consumed to put two and two together and recognize that perhaps at that very moment John was also testing or toying with me, challenging the security of my sexual and gender identity. Maybe he was looking for a convenient opening to “come out of the closet.” For me, it was neither the first nor the last time I experienced heterosexual-homosexual conflict and all the taboos surrounding it while at Yale. I can only imagine what John went through in his journey to self-identity both at Yale and beyond.

John Anton Tardino was the youngest child of an authentic Italian family, born and raised in Merrick, NY. Much was expected of him, and much did he deliver. John was a romantic, a handsome 20th Century Renaissance man who caught the eye, imagination, and heart of many young women, and dated many, though no single one exclusively. His Whiff nickname, “Mentalre,” was amusing and a propos only because it was so far it from the truth! He was a scholar who exhibited a voracious appetite for anything new and novel, and applied this yearning for knowledge to his Independent major in American Studies and to recreational experimentation during the psychedelic 60s and 70s. John was also a natural and talented musician and singer — a creative, artistic, experimental soul who perfectly embodied Marshall McLuhan’s notion that “the medium is the message.”

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

I first met John in the Yale Freshman Glee Club and he and I became roommates in Silliman College from sophomore year through senior year. While we parted company when it came to experimenting with recreational drugs, we were close collaborators on all sorts of experimentation. Probably the best example of this occurred when he took Josef Albers’ course on color theory in the School of Art and Architecture. John was given an assignment to manipulate the three primary colors of light: red, blue, and green. John had the idea to take Piet Mondrian’s Study No. 9 and recreate it in infinite variations using light, as opposed to fixed pigment. Given our shared fascination with the arts, our collaboration on this assignment was natural — I, the more the technical “nerd,” John, the contemplative artist. We constructed a shallow wooden box whose dimensions were exactly that of the painting, and made compartments corresponding to the various sized rectangular components of the painting. Into each compartment were put red, blue, and green C7 blinking Christmas tree lights, which we then covered with a thick milky white translucent Lucite. The resultant Mondrian No. 9 lightbox was a huge success, in part because people watching it while listening to any kind of music could enjoy a psychoacoustic phenomenon in which the brain automatically associated the rhythm of the randomly changing color panels with the various rhythms of the music!! Not only was it very popular among those experimenting with marijuana, hashish, peyote, psilocybin, and LSD, but it also made a splash among visual and musical artists. John and I could not make them fast enough — requests flooded in from the likes of Professor Paul Rudolf, then Chairman of the School of Art and Architecture, to Michael Rockefeller, then Chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank (whose unique lightbox was crafted to the shapes of the Chase Manhattan Logo), to New York fashion designer, Alexander Julian. We, together and separately, made many as wedding presents for our friends.

John took everything seriously, and at times could be quite stubborn in his idealism. Very much influenced by Yale Chaplain Reverend William Sloan Coffin, John was an active, vocal opponent to the Vietnam War — so much so that when Yale President Kingman Brewster requested that the Whiffenpoofs sing for First Lady “Lady Bird” Johnson (whom he was hosting on her “Greening of America” tour), John refused to participate on the grounds that her husband, President Lyndon Baines Johnson, was prosecuting the war in Vietnam.

The last time I saw John was when I was visiting New York to attend a medical conference. By this time, he had established his family medicine practice in Manhattan. Sadly, it was not too long thereafter that I learned the most enduring heartbreak: that my exceptionally talented and accomplished friend John Anton Tardino had died in the first wave of the AIDS epidemic. Though well aware of AIDS, the naïve and unsuspecting side of me was totally caught off guard. To this day, I truly regret not having known so that I might, at the very least, have shared just a little bit of his burden, provided him support and consolation. But it was a time when there was such social stigma attached to both being identified as gay and to having AIDS that it was all a closely guarded secret and many, John included, suffered in painful silence.