I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

José Angel Vigo was born in 1950 in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. Of humble origins, Vigo demonstrated an early talent for writing. While he was in elementary school, his family emigrated to New York, where as a teenager, he helped support his family by working in a jewelry shop in Manhattan’s Diamond District. He won a scholarship to Cornell University, but dropped out after one semester. He later attended Hunter College, from which he graduated summa cum laude in 1978 with a degree in Language and Culture Studies. He continued his studies in social, cultural and linguistic anthropology, receiving his masters degree in 1980 from Yale University, where he stayed on as a doctoral candidate.

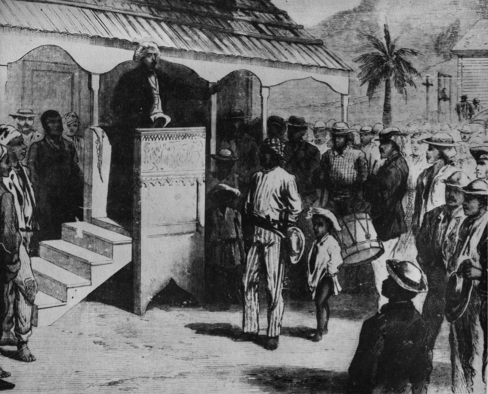

From 1982 through 1983, José conducted fieldwork in Samaná, Dominican Republic, researching the Creole language and traveling frequently between the Dominican Republic and his hometown in Puerto Rico. His dissertation, Language Maintenance and Ethnicity: A Sociolinguistic Study of Samaná, Dominican Republic was meant to examine the processes of language shift among the descendants of a 19th-century colony of American freed slaves. Due to his illness and financial hardship, it was never completed.

Although he was offered a position in the English department of the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, the region’s electoral tensions and José’s strained finances hastened his return to the United States. In the mid 1980s, Vigo taught African-American studies, anthropology, and Puerto Rican history at Yale, Wesleyan, and Rutgers Universities, and worked briefly for the city government of New York. He died of an AIDS-related illness in February 1987. His unfinished doctoral research and personal papers are housed in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.

III.

I write this remembrance of José A. Vigo on Good Friday, the anniversary of the oral portion of his preliminary doctoral examinations at the Department of Anthropology of Yale University, in the early 1980s. Why hold the oral exam on Good Friday, the height of insensitivity toward a Catholic person – or Christian person of any denomination? José said: “That was the only day they could get together…Talk about crucifixion!”

This illustrates the consideration they had for him at that department. I do not know who was on his committee, but their actions spoke loudly. Not only did they hold his oral exam on Good Friday, but he did not receive any grants or support for his doctoral research and had to take out loans. Yet he was not only a bright and dedicated anthropologist, he was also a meritorious minority student in many senses: racially, culturally, and – most significantly – economically, which was the most notable handicap compared to the other students. He said that when he walked across the Yale campus, he felt eyes were upon him, as if people were saying, “There goes our minority!” I told him, “You are less a minority as an Afro-Puerto Rican than you are as a New Yorker!” Because he certainly was both at the same time: an Afro-Puerto Rican and very much a New Yorker.

José first introduced himself to me in a letter in 1982 or 1983, when he wrote to say that he had been trying to locate me for a couple of years. He said he was a linguistic anthropologist and mentioned that he had studied the Haitian Créole language at the renowned Créole Institute of Professor Albert Valdman at Indiana University in Bloomington, and that he wanted to do his doctoral research in the Dominican Republic. He was fluent in both English and Spanish, had studied Créole, and was seeking a project in linguistic anthropology. As a linguistics scholar with similar interests, I was able to recommend the perfect research topic for him: the traditional trilingualism of Samaná in the Dominican Republic. Créole speakers in Samaná today (who are also fluent in Spanish as well as an archaic form of English) are descended from Haitians who settled there in the early nineteenth century; I was interested in determining whether the Créole they speak is an archaic form of the language more closely related to French, and how it compares with contemporary Haitian Créole.

José accepted this suggestion and he spent about a year in the town of Samaná to investigate this trilingualism, with a focus on Créole. The last time I saw him there was the first of November, probably in 1985. I wanted to attend a traditional cantica, or prayer service sung a cappella in French on every November first, or All Saints Day. Eloisa of Savaneta, the sponsor of this annual vow to honor the dead, was a fishmonger who would go down the mountain on foot to Villa Clara, on the Samaná Bay, to buy fish from the fishermen, and carry it up in a batea on her head to sell it up at Savaneta.

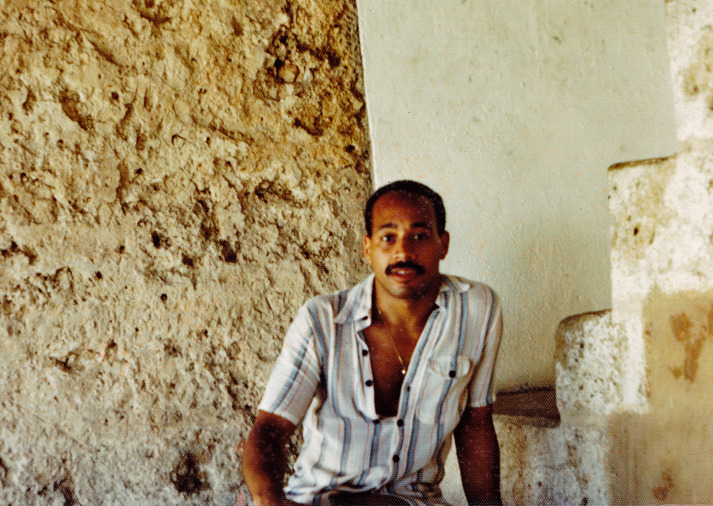

So José and I got together in town in the morning and we rode a pickup truck – the only form of public transportation – from town on the bay side to my rural property on the Atlantic coast, eight miles away. There he helped me fix something or other at the house, which was an old, wooden shack and in constant need of repairs. He was generous with his time and a person of solidarity. When I thanked him for his help, he replied, “Aren’t we colleagues?” Then we walked to the beach of Playa El Valle, two minutes away, where he took a picture of me at the big rock at the mouth of the San Juan River.

In the afternoon, we set off to Savaneta; there was no vehicle, so we went on foot. We must have walked about four hours. When we got to the house in Savaneta, it was dark. The neighbors said Eloisa had died and the cantica was no longer celebrated. So we walked back to town, arriving about midnight. This illustrates why his research was urgent: the old traditions were being abandoned forever. And so it has continued, such that the oral traditions (indeed, the trilingualism itself) which I first encountered in Samaná in 1972, and which José subsequently studied, are no more.

After José’s research, he returned to New York and had to find a job. He got a research position for the city government of – I believe – Brooklyn. They commented how fast he could research a problem or topic compared with their previous personnel; of course, as a doctoral candidate, that was no surprise. He also got an adjunct position at Rutgers University, the public university of New Jersey. He rode the New Jersey Transit line down to teach those classes. Why he did not get a dissertation-writing fellowship or some assistantship or adjunct position at Yale, I do not know. Because he had to work more than full time to support himself and his mother and pay down his loans, he never did have time to finish writing his dissertation. I myself relocated to the United States in January, 1985, working at Brown and Harvard Universities until 1987. During this period on the East coast, I saw José several times in New York. Once he arranged an invited lecture for me at Rutgers, and I accompanied him down to New Brunswick. I also met a favorite woman friend of his, an artistic photographer about ten years older than he, who lived and worked in Greenwich Village, I believe.

I believe the last time I saw José was in early December of 1986. I had gone down to New York and learned he was ailing. I traveled by subway to where he was living, I believe in Brooklyn. He looked like Ghandi: thin and brown. He was in the company of kind male friends. He wanted to tell me what his illness was but did not know how to approach it, since it was an illness associated at that time exclusively with male homosexuality. We had never discussed his sexual orientation; our conversation was always on a professional level. Finally, he finally thrust a printed article about HIV in my hands; after I read it, he said that this was what he had.

Acronyms such as “HIV” and “AIDS,” and the terms they stood for were not so commonly known then—especially “HIV,” which in fact I learned about at that very moment. But I understood what he was saying, and I also understood that it was terminal. This was several years before that marvelous “cocktail” of anti-viral medications was developed that has made HIV manageable rather than a death sentence. For José it was a death sentence. So he was trying to tell me in the same breath that he was both homosexual and going to die soon.

I asked him if his mother knew he was ill. He answered that his mother did not even know he was gay. I said, “Tell her; she probably already has guessed. It is urgent that she know everything.” I also said that on his good days he should get his papers in order and find a home for them. I could see that he would not be able to finish his doctoral dissertation. But if he had his papers in order, others could pick up the ball where he had dropped it. Later I learned that his papers had been deposited at the Schomberg Center in New York City, a center of African-American Studies founded by a Puerto Rican. Perfect.

During his illness, I communicated with his friend the photographer, who also thought he looked like Ghandi. She was the one who informed me when José died, in February of that year, 1987, and described his memorial. I promised her that I would dedicate a book to him; she said that she would do the same. Indeed she did dedicate a book of photographs to his memory and it was published; so did I, but my book is still yet to be published. Then, in about 1998, perhaps, I received a postcard from a New-York gallery about a memorial exhibit, if I recall correctly, of her photographic works; she, too, had died.

Many thanks to the people who are gathering remembrances of José A. Vigo. Younger people may not be aware of the desperation, twenty-five years ago, caused by a disease whose victims were not only condemned to die but marked with the social stigma of homosexuality. The “Christian” discourse of the time even implied that, because of their supposed deviance, they in fact deserved the disease as their penance. It is thanks to the efforts of the same sort of people, who are compiling these remembrances today, that this attitude has been silenced. And, thanks to medical researchers, HIV is now a manageable disease. Would that the medical “cocktails” have been available for my friend and colleague, José Vigo! The world would be a better place were he still here.

I met José when I was a linguist teaching at Hunter College and the doctoral program in linguistics at the City University of New York Graduate Center in the 1980s. We shared an interest in Black and Creole language varieties. I was working on a book entitled Pidgins and Creoles and José, who had studied at both institutions, had received a scholarship to do a dissertation at Yale on the early nineteenth century variety of English that had been taken by free black emigrants to the Samaná Peninsula of the Dominican Republic. I acknowledged my indebtedness to Vigo in my book, but as things turned out his dissertation was never completed.

It´s relevant that José was a very dark-skinned Puerto Rican who grew up in Brooklyn. His father had died an alcoholic and his sister had died a drug addict, and he was everything to his mother Mercedes, who had gone back to Mayagüez to live. I was getting ready to go on sabbatical to the University of London in 1986-87 when he came over to visit me and my partner to tell us that he was leaving Yale to take a job with New York City because he needed the health insurance.

My partner, who was also working on a book, stayed on in London for a few more months when I came back to New York City in August, 1987. I called José to see how he was doing and he said he had been sick. He called me back a few days later to tell me that he was going to check into a hospital. I insisted on coming with him to help him carry his suitcase. I think the hospital must have been understaffed over the Memorial Day weekend, because he got very sick and no one seemed to notice. I visited him and he improved slowly and eventually he was released. He lived alone in an apartment in Brooklyn and there were volunteers from the Gay Men´s Health Crisis Center that came by to take care of him. Actually, I was just one of many people who started coming by to take care of him, and I began to realize how many friends he had and what different circles they came from: straight, gay, black, white, Latino, Anglo, male, female, scholarly, street-wise. It was because José was all of these things himself and he never let himself be pigeon-holed as any single one of them. Which didn´t mean that we could all get along, especially as he got sicker.

He started needing more and more care, and I suggested that he call his mother Mercedes to come from Puerto Rico. He said he couldn’t tell her over the telephone that he had AIDS because he had never told her that he was gay. So I gave him the airfare for her to come to New York so he could tell her in person.

One night at about 3 a.m. I got a call from a social worker at a hospital who told me that José had been taken into emergency and that he was very sick. Mercedes was with him but she didn’t seem to understand enough English to realize that he had AIDS. She was staying with him in his very small apartment and of course she needed to know that for her own protection. Finally I got a Puerto Rican Lesbian friend of José who was a dentist to explain things to Mercedes. It was okay because she was a woman and a doctor and she could say it all in Spanish. Later, after José had died, Mercedes said that she had known for a long time that José was gay but he never seemed to want to talk about it.

The funeral was in a dangerous part of Brooklyn where very few white people ever went. Mercedes belonged to a Pentecostal Protestant church and their preacher led the service. Some of José’s scholarly white friends went into culture shock because of the music and shouting, but I´m sure it was right for Mercedes and that´s what mattered. There was also a very white English lady who was the chair of Yale´s anthropology department but she spoke not as a professor but as a mother and said the same thing that other people from Yale had told me. Yale failed its minority students because it didn´t know how to socialize them into becoming academics. It wasn´t because people at Yale were overtly racist; it was just that they didn´t—couldn´t—reach out to their minority students to integrate them into what was going on academically so that they could compete. I wonder if this woman could have realized this if she had been a white American. Anyway Mercedes hugged her.

A few years ago I was invited to give a series of lectures at the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras, and a colleague of mine from Mayagüez drove me there to visit Mercedes. She had a neat little apartment but no family but she has her Pentecostal church community and she seemed glad to see me.

My Last Best Friend

I turn seventy soon—an age in which one may rightfully claim to have had a “history.” My own past has been sweetened by the presence of a half-dozen best friends. I found my first best friend in fourth grade. My only after-school fight erupted in seventh grade where, despite ringside goading, my opponent refused to hit me in the face: we, after all, were best friends. In high school my best friend and I were both for the war in Vietnam; but after graduation, as a student at the University of California at Berkeley, I was quickly brought into the anti-war camp. I met my fourth best friend in my junior year there. He travelled to Mississippi and Louisiana in the summer between our junior and senior years to register voters. Out of college, my next best friend and I imagined ourselves political radicals fighting for the oppressed. I was Malcolm X; he was Che Guevara. Given the events of those last fateful years, and then his assassination, I still find reasons to identify with Brother Malcolm. My best friend, however, became a successful Wall Street lawyer bringing home the big bucks. This, of course, forced a crisis of conscience that he settled by breaking with me who had once been audience to his young man’s radical dreams. He, like two of my other best friends, is straight; they are also grandfathers. Of the others, my first best friend, who never married, lives alone and likes to bowl. Two of my best friends are gay, and all my half-dozen best friends are alive today except one. His name was José Vigo.

José was thirty-five or so when he died—something like half as long as I’ve now been alive. We met one autumn afternoon aboard Manhattan’s 14th Street cross-town bus. A couple of years younger than myself, he was as brown as me but with handsome Latino features and the ubiquitous moustache that Puerto Rican boys seem to grow by the time they take their First Holy Communion at age seven. While still in elementary school, he emigrated from Puerto Rico to Brooklyn with his parents and his younger sister, Miriam. He was introspective, brilliant and charismatic (though he liked to wait, to judge the scene, before stepping forth). At eighteen, he was admitted to Cornell University. (I think he won a scholarship.) He lasted one semester. It was all the snow, he complained. Maybe, but certainly he also missed the Big Apple where, unlike sleepy Ithaca, a fresh cavalcade could be daily observed moving down familiar streets. As for our time together, with José and me for the most part it coincided with that cultural blip known as “disco fever”—when the red apple-of-pleasure hung over thousands of dance floors lit by revolving mirrored balls, the fruit within delectable reach, its skin unblemished, its juice sweet. None of us could have guessed.

I joined José and his crowd on weekends but otherwise I was busy writing my dissertation at Columbia University while, at the same time, commuting twice weekly to New Haven where I was enrolled in Yale’s Masters Program in Environmental Design. And four days a week, I was serving as a fulltime tenured counselor at Queens College. Nevertheless, best friends we became. The fact that we were never lovers helped when we decided to spend a week in Puerto Rico. He liked showing me his island.

Then in 1980 things changed. I was granted sabbatical leave from Queens College and with my dissertation and masters thesis both earlier accepted, I left for Oxford and a post-doctoral fellowship. By then José had applied for admission to Yale, was accepted, and had begun classes. I recall the back-and-forth of letters—the international letter-and-envelope all of one blue sheet. When I returned to the U.S. nine months later, I chose to settle in Northern California and José and I continued to exchange letters; sometimes we talked by phone. A couple of years passed. Then I got the letter in which he explained that he was in the hospital and diagnosed, he wrote, as suffering from that mysterious disease coming much into the news. I flew back and stayed with him a week. When I returned to California, we talked by phone over the course of the next several months, but I was never to see him again.

José Vigo, with his many gifts, was shadowed by tragedy. His father was abusive and as a teenager, José tried killing himself by swallowing ant poison. Later, when the father abandoned the family, José’s job in Manhattan’s diamond district helped to ensure that the needs of his mother and Miriam, still living in Brooklyn, were met—but this was not always easy. Then one night, partying in the Bronx, Miriam overdosed. José got the call and raced to her side and was with her when she died. José then took the subway home to his mother and explained that now it was just the two of them.

José never told his mother that he was gay and when he got the AIDS diagnosis, he kept this to himself as well. She surely guessed the first but was not prepared for the second. It was still in the early days of the epidemic and José, living on the Lower East Side, had been able to keep much of his doings private. Only when he was in the hospital for the last time, his mouth a nest of sores, did he ask her to visit. He felt the need to apologize, he told me later; but otherwise he did not share any more of their conversation. I knew that this was the most difficult thing he’d ever had to do. He was dead within three days.

I did not become the academic I was expected to be, nor the writer I hoped to be. And I never found another best friend: I never looked.

Eighteen years ago I was ordained as a Buddhist monk and today live in a trailer in a Redwood forest in Northern California. I often think of José and wonder how long was he in attendance at the university. Had he requested a medical leave or did he just drop out? I know for sure two related things: He’d be pleased to be a part of the AIDS Memorial Project because, while a student at Yale, José Vigo was happy.