I.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

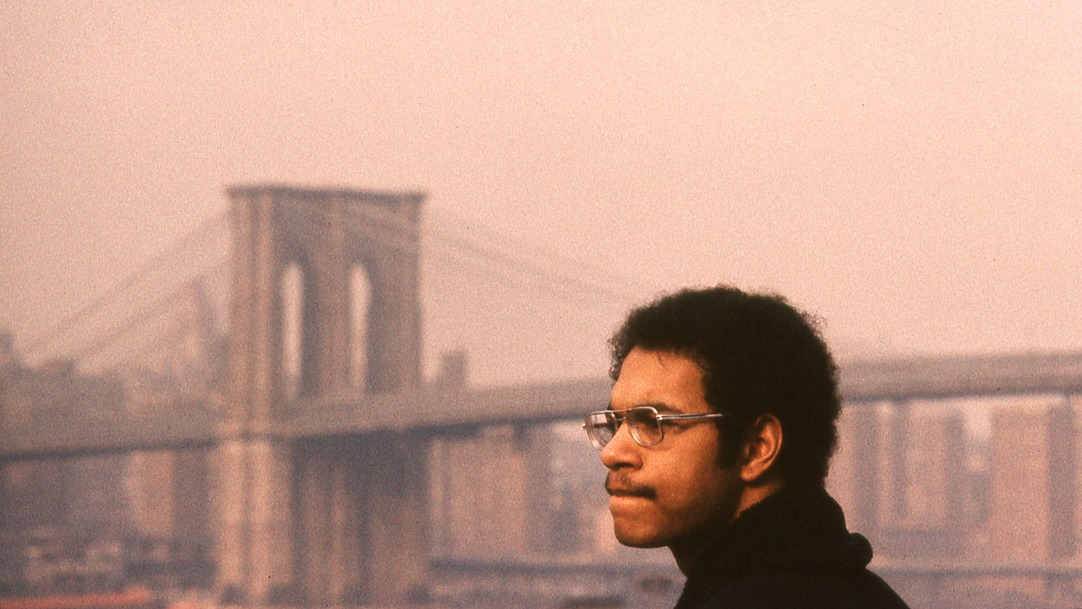

Warren P. Smith was vice president counsel in the law department of the Home Life Insurance Company. Born in Chicago on April 15, 1952, Warren grew up in a suburb of Minneapolis with three brothers, a Caucasian mother, and an African-American stepfather. He attended Hopkins Senior High, a large, predominantly white public school.

He majored in English at Yale and wrote for the Yale Daily News. In August 1972, he published a story in the Yale Lit intricate vignette about an unhappy Chicago woman who follows her husband to New York on a winter business trip. On a snowy evening she leaves her hotel, heads to Central Park in search of Robert Indiana’s LOVE sculpture, and encounters a man in an ermine coat. As the story ends, passersby discover her murdered in the park and wonder why she had come there on a winter night: “Those staring at Mrs. Patterson were forgetting that the night before the moon was full and snow was falling. The night before, Mrs. Patterson was forgetting that the moon is uninhabitable, snow is always cold, and that an ermine is just a weasel in the winter.”

Warren graduated in January 1974 and then traveled to Ebersberg, outside Munich, for a three-month fellowship from the Goethe Institut to study German. Upon his return, he had potential employers in a number of fields hoping to hire him. “In a room filled with about forty Ivy League grads to be, I was the only black,” Smith wrote of an information session at Northwestern National Bank. “The bankers came up to me before the program started, after the program was over, and after the meal at the Minneapolis Club . . . . Let’s face it, I am not the brightest thing to hit Minneapolis, but a black Yalie is rarer than AB negative blood, and if these big companies don’t hire some schwartzes, they are going to get fined.”

Smith was, in fact, extremely bright. After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1977, he was quickly recruited by Debevoise, Plimpton, Lyons & Gates (now Debevoise & Plimpton), one of the most selective law firms in the country. From there, he moved to Willkie Farr & Gallagher, the Equitable Life Assurance Society, and, finally, the Home Life Insurance Company.

He died in Union City, New Jersey on July 18, 1987. He was 35.

III.

I was a freshman at Columbia. We were organizing a rock concert on the South Lawn, and it was my job to help clean up after it was over. This kid came walking up to me—why he chose me out of all the people he saw I have no idea—and introduced himself. He said he was from Yale, and that he needed a place to crash.

Happily I erred on the side of incaution: “You can crash in my room,” I said. We had a great, all-night conversation, and left on friendly terms, and periodically through that year he would come down to New York. It should be said right away that neither of us identified ourselves to the other as gay. I had my girlfriend, and he had his girlfriend.

One of the things I’m glad to have lived through was a time when identifying yourself as gay was such a peril that you did so very carefully, in a calculated and strategic way. As painful as that experience was, the reward of finding someone whom you already liked who was also gay was tremendous. It was like fireworks. Two people on an island in the middle of the ocean.

I was out on the West Coast that summer between freshman and sophomore years, and Warren said, “Why don’t you stop by Minneapolis on your way back to Chicago?” Which is actually an absurd detour if you’re coming from San Francisco, but I said, “Sure, I’d love to see Minneapolis.”

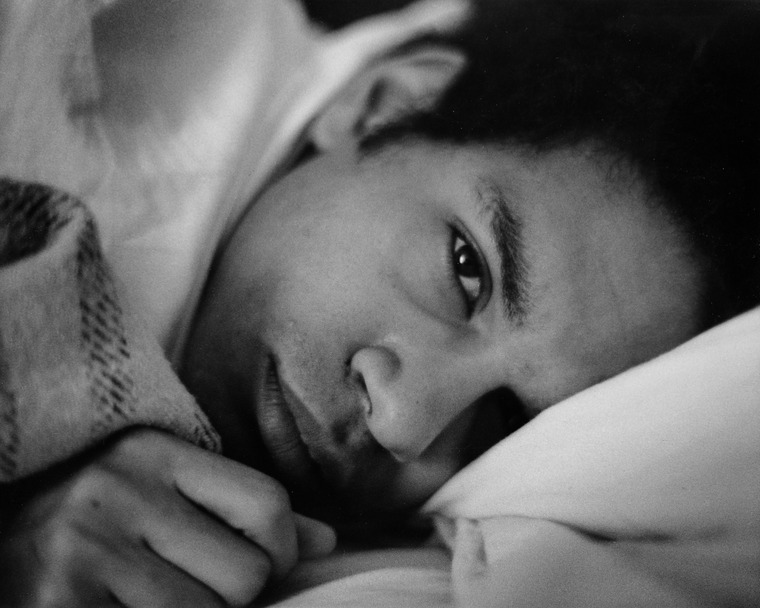

We were staying at Warren’s house. His parents were not there; they were up in Crow Wing County. And the first night he stayed in the bedroom, where he had a picture of his girlfriend, and I stayed on the living room sofa. And the second night, it was very hot, and he said, “Look, the bedroom has air-conditioning, and the living room doesn’t, why don’t you stay in the bedroom.” “OK,” said I.

We got into bed and looked at one another across the space of the pillow. And it was, “Are you thinking what I’m thinking?” And, “I think I am.” And there was no stopping us at that point.

We had a tempestuous, fairly long relationship.

We were apart for the first semester of sophomore year, and then I transferred to Yale. Though I was assigned to Pierson, I basically went to live with Warren in Trumbull College.

The next summer, 1972, a bad, tumultuous, passionate, romantic, hate-you, love-you summer, I took it upon myself one night to write a scorchingly graphic letter. And before that letter reached him at 9600-A 17th Avenue North, Warren’s mother, Rita, opened it. So her introduction to his being gay was…it didn’t go down very well.

He was very close to his mother. His mom was white, his dad was black. One half of his line was German. That’s why he was at the Goethe Institut—not usually the chosen destination of young African-American scholars. He had no relation to his biological father, and with his adopted father he had a distant but fairly cordial relationship.

He was Pooch. Not a name of my invention. As a kid he had been a very jowly baby, so he was nicknamed Pooch, and he once made the mistake of telling me that. And that was the end of that. So he was always Pooch.

I remember once, when he’d come to New York, we were walking along Christopher Street. We were both leading a largely closeted life to the outside world, and I remember it suddenly dawning on me, and saying, “Pooch, if someone sees us here, they’ll think we’re gay.” And he looked at me like, as we would say now, “Uhhhh, yeah.”

We both liked the Jackson Five. That was not something that two semi-grown men had any business liking. But we both liked the Jackson Five. We went to see them in concert in Minneapolis. We saw Joni Mitchell in concert in Minneapolis. We saw Bette Midler in concert at the New Haven Coliseum.

He graduated after the first semester of his senior year and went off to Munich for a fellowship there. I went to Paris on spring break, and Warren came in from Munich. We got to Chartres, and we got to Sainte-Chapelle, but then we just had sex in the hotel room around the clock.

On that trip, we had agreed by letter that we were going to rendezvous in Paris on a certain date and a certain place and time—in the Place du Parvis Notre-Dame, on a Tuesday at noon. I’m airborne to Paris, aboard Air Canada, and the pilot says, “Folks, they’re really socked in at Orly, we’re not going to be able to land there, so we’re going to go to Brussels. And then we’ll put you on a Sabena flight into Le Bourget.

“Oh, God,” I thought. I’d given myself a couple of hours, but I hadn’t given myself time to go to Belgium instead. No cell phones—none of that. I got to the Place Notre-Dame three or four hours late. No Warren, of course. Then I got to the hotel. “Oh yes, Monsieur, this Mister Smith, yes, he was here, but you were not. He has left.” I was AWOL from my family. They didn’t know where I was. I think I told them I was seeing some friends in Boston or something. I didn’t tell them I was going to cross the Atlantic to go to Europe. And now I’m here, and he’s gone . . . What was I going to do? I guess I’d turn back, or spend a day or two here and then go home, or something . . .

I had to stop by the American Express office. I was coming up the Métro steps. And he was coming down.

That’s how we found one another.

I had just happened to say, “Alright, fuck it, I’m going to American Express.” And he had just been to American Express, on his way to Gare de l’Est to go back to Germany. At that moment.

He’s the only person I share that with. He’s the only one who knows what the color of the sky was that day, and what the temperature was. What it was like: he’s looking down, and I’m looking up. “There you are.” And now, it’s just me. The chance to bring that to life is a very special.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

Warren’s life in New York as a corporate lawyer was, I think, an especially compartmentalized one. He was recruited by Debevoise & Plimpton, as white-shoe a firm as you can work for. And at the same time he was an insatiable hedonist. He loved the nightlife. In that way I expect he led exactly the sort of bifurcated existence that was so common in those days. Absolutely straitlaced corporate lawyer by day, and satyr by night.

No longer lovers, in New York, we were more like fond, battle-wearied friends. We would have lunch together, or dinner together… and then, I forget what year, but he called to let me know that he had AIDS.

I wrote his obit for the Times.

I should say that Rita was there for him in the closing months of his life. And I should also say that, when I was writing the obit, I asked her, “May I specify in the obit that he died of AIDS?” She wasn’t at all sure about that, and with good reason: in 1987, most obits did not specify that. People died “after a short illness.” Or, “the family would not discuss the cause of death.” And without any persuasion on my part, except for my saying, “Rita, for someone to know that the vice president of the Home Life Insurance Company has died of AIDS…” And she said, “Yes. You can say that.”

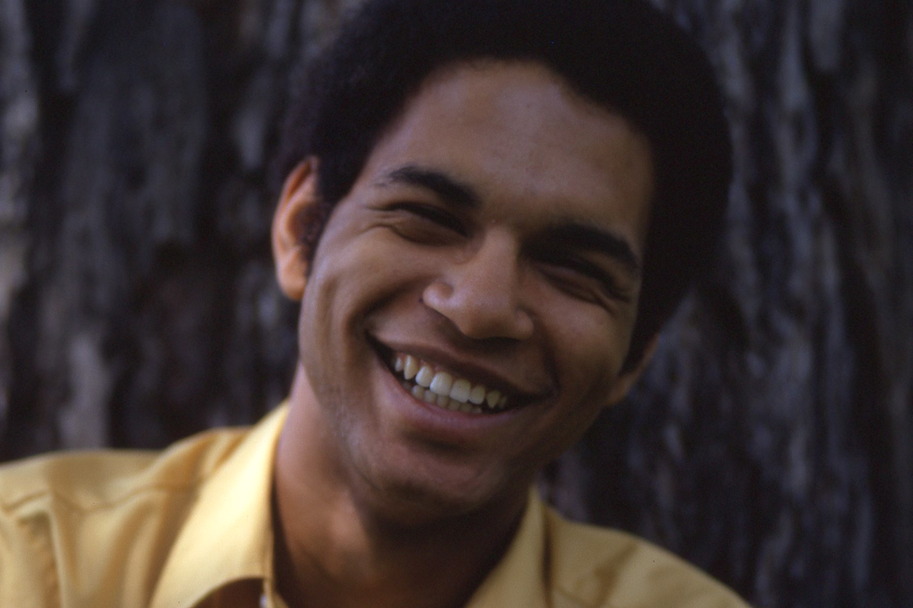

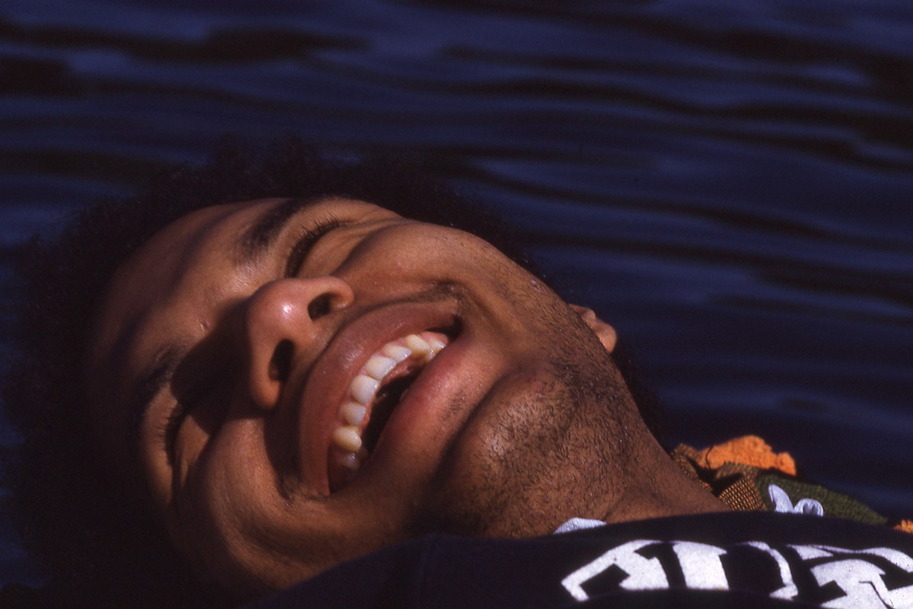

Warren and I met in the winter of 1977 on the dance floor of 1270, a gay bar in Boston, one of only a couple at the time, and the one with the best disco music. I remember the bar would start the music at 9:00 pm, so my friends and I—we were professional modern dancers—would arrive early to take over the dance floor for the first hour. We loved having the place to ourselves—getting our “ya-yas” out, letting out all the stops, spinning and flying through the space until the boys began to arrive an hour or so later.

Warren’s smooth way of catching the upbeats with his hips caught my eye early one evening, and as we danced together through several songs, his dazzling smile and his delight in the joy of dancing caught my heart. We dated continuously through the next six months while he finished up his law degree at Harvard, studied for the bar, and began practicing law. I was also busy, performing with Concert Dance Company and teaching adult and children’s dance classes; but we began to reserve the weekends for us. Although we spent hours out dancing, and more hours having great sex and falling asleep snuggled together, what I remember best is Sunday mornings, waking up slowly to the light streaming in through the double windows of his Beacon Hill studio, listening to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, drinking fresh-squeezed orange juice and fresh-pressed coffee, eating freshly bought bagels from the corner bakery, and discussing articles we read in the Boston Globe.

As a black guy with a Harvard Law degree, he was in high demand. When he received an offer at a big law firm in New York City, it was no surprise. He wanted to take it, and he wanted to take me with him.

I had no contacts in the modern dance scene in New York, though, and leaving Boston would mean leaving all the tenuous security I had spent four years cobbling together from various performing and teaching gigs. My tiny income felt big to me, but the money Warren was offered could clearly support both of us in a style I could never afford on my own. Although my heart was ready to follow him anywhere, my head was still attached to reality. So I drew up an agreement (on a yellow legal pad!) that stipulated that Warren would support me for a year while I went to auditions and classes and built a network for myself in New York. He didn’t hesitate to sign.

Of course there was nothing really legal about that document, and we both knew it, but the act of signing it together felt like a bold political statement about what we felt were our rights to love who we wanted. And it felt to us at least as binding as the lease on the apartment Warren found for us on 75th and Broadway.

So I moved with him, and we explored our new NYC life together for the next 6 months, he adjusting to long workdays at the firm, and I running all over the city from class to rehearsal to audition. On the weekends, we’d both go out dancing.

It was on a vacation to Key West the following winter (which he must have paid for) that we realized we both wanted to explore other relationships. And when we got back to New York, I simply moved my stuff into the second bedroom in our apartment.

Way beyond our agreement, he continued to pay our rent for at least another year, while we both went out night several nights a week, and brought dates back to the apartment, our beds separated only by a thin wall.

Eventually he met and started seriously dating another guy. When they decided to move in together, they found a place in the West Village where they could be close to the dance clubs, and he could be closer to his work. I moved to a cheap place in a risky area of Brooklyn.

No longer in each other’s daily lives, we quickly lost touch, although I often wondered what happened to him. Warren was my first live-in boyfriend, and I learned a lot from him about savoring the best our culture has developed. I also learned the value of following through with agreements.