I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

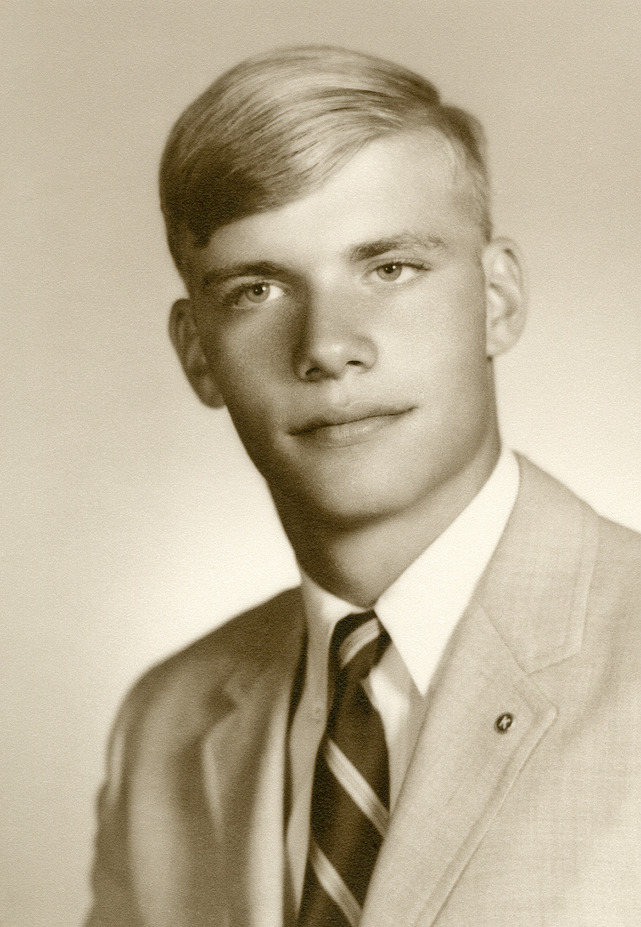

Michael D. Palm was a financier, an innovator of reinsurance, and a major philanthropist to LGBT organizations and the arts. Michael grew up in Reading, Pennsylvania, where his father was a policeman and city councilman. He attended Yale on a full scholarship and became captain of the volleyball team. After graduating in 1973 with a degree in English, he pursued a PhD at Harvard with plans to become a teacher.

After completing a master’s degree, Michael taught at an English language school in Tehran, where he met Steven Gluckstern, one of the school’s principals. The pair became business partners and started an educational consulting firm in Athens before returning to the US. Michael continued his studies at Harvard, but before finishing his doctorate, he decided to take a position with the Bank of Boston, advising on lending in Africa.

In 1986, Michael joined Gluckstern at Berkshire Hathaway, where Gluckstern worked with Warren Buffett. In 1988, after Buffett turned down their plan to start a reinsurance business at Berkshire, they started their own company, Center Re, which provided insurance to insurers. Reinsurance is now an industry standard. Centre Re’s primary investor bought the company a few years later, and Michael remained as vice chairman.

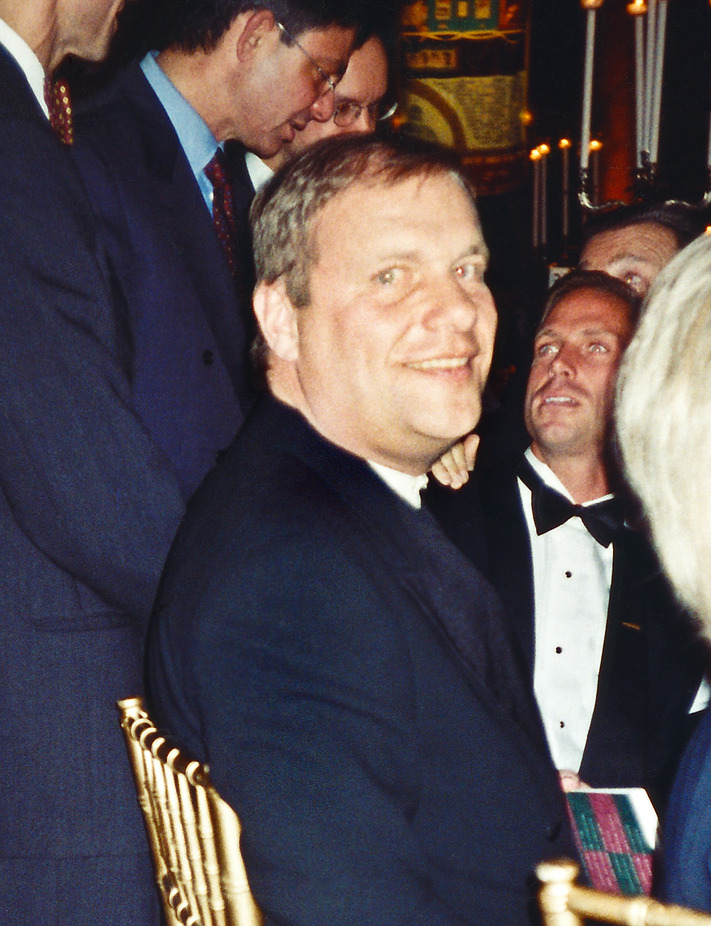

Michael retired in 1993, devoting himself fully to philanthropy. He served on the Board of Directors of Human Rights Campaign, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. He founded the Michael D. Palm Foundation, which has contributed over $10 million in gifts to LGBT service organizations and the arts. In 1996, the foundation awarded a $2.5 million capital gift to GMHC to establish the organization’s headquarters in New York. Michael also supported AIDS Walk, Treatment Action Group, Empire State Pride, and HIV/AIDS research at Cornell.

A lifelong musician, Michael took lessons from pianist Earl Wild and owned several pianos, two of which he stored in his home across from Lincoln Center. He anonymously supported emerging artists and arts institutions, including the Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and Classical Action, a performing arts collective benefiting HIV/AIDS research.

He died of AIDS-related heart complications at his home in Telluride, Colorado, at age 47.

III.

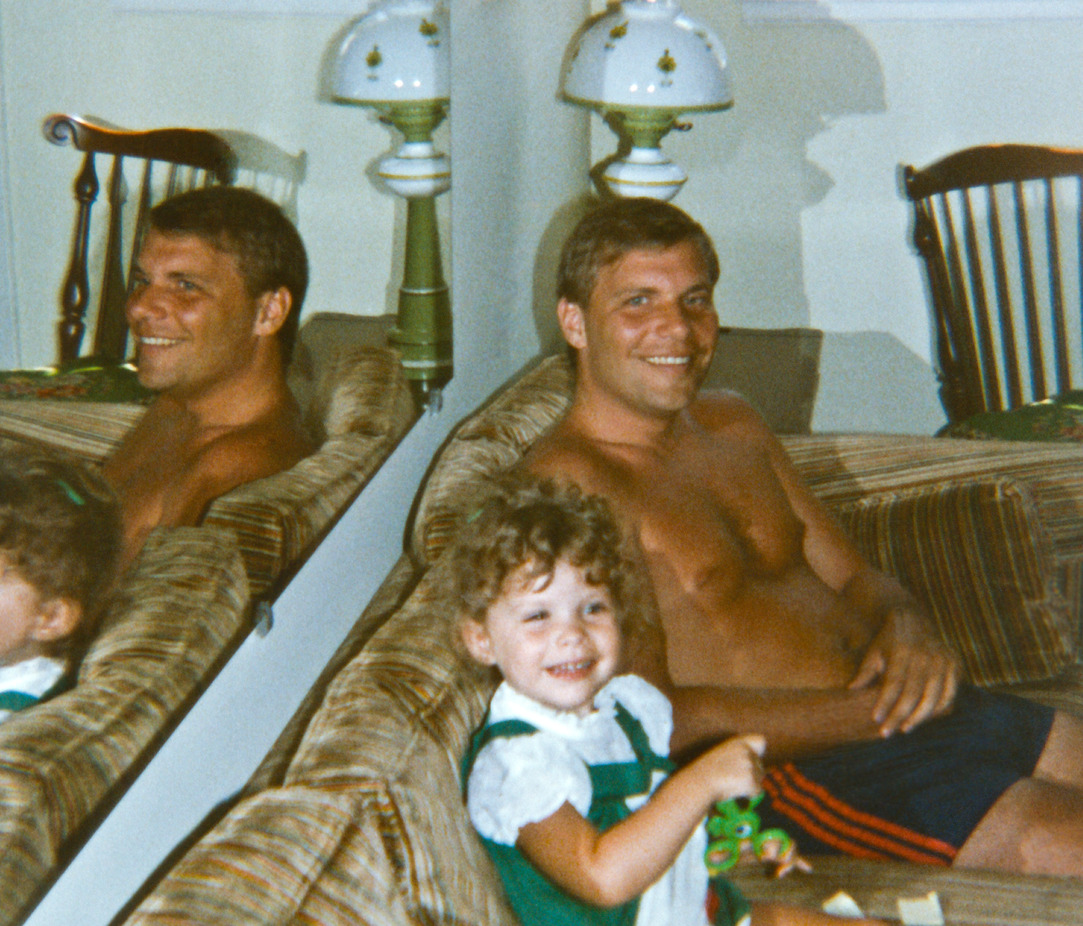

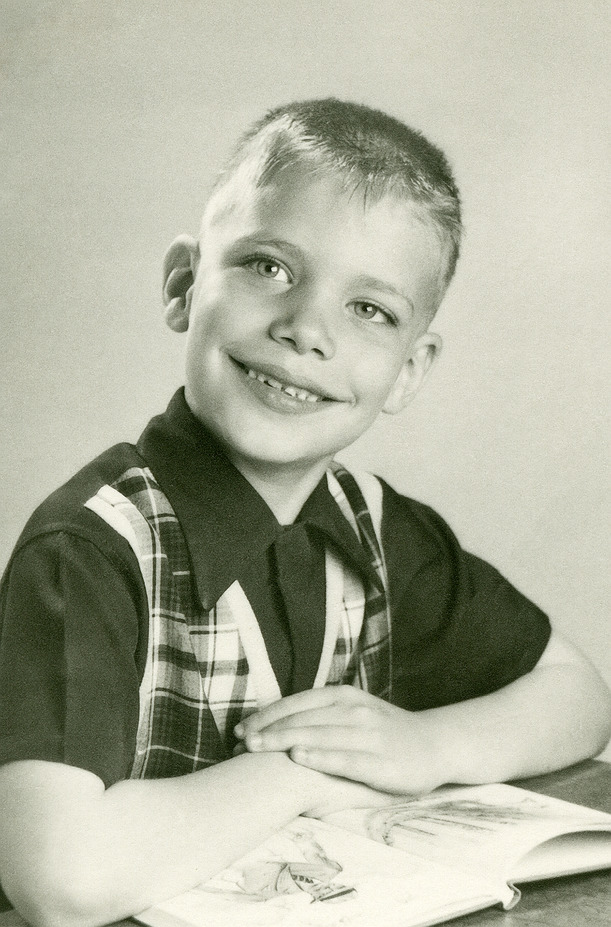

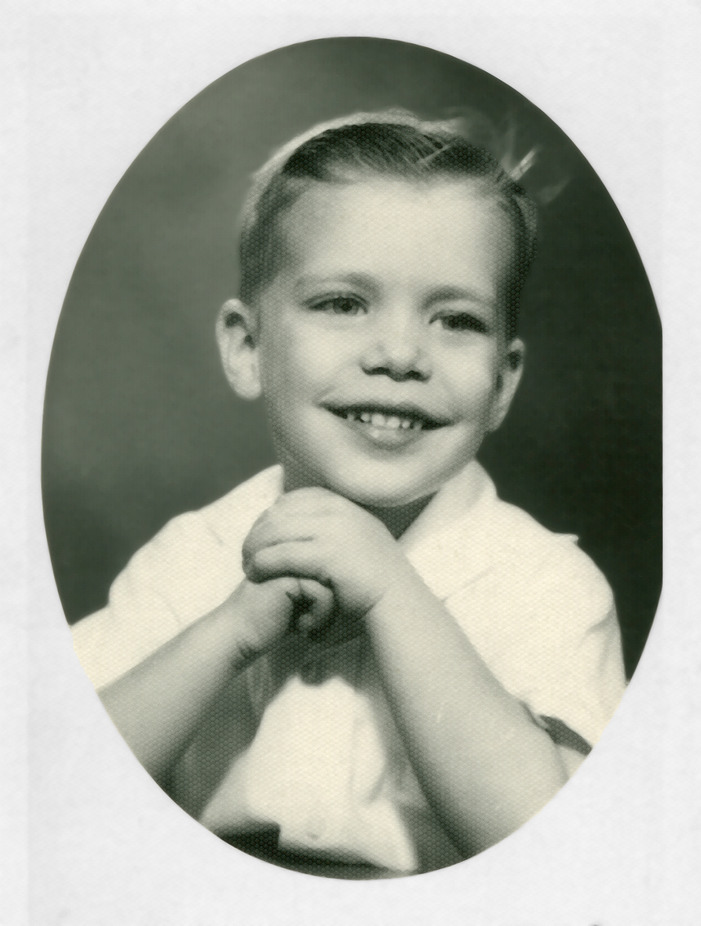

Michael was my big brother. Those of you who grew up being a little brother or sister to someone like Michael can appreciate this: Michael was smarter than I was…he was far more musically talented than I was…he was more athletic. He got into a lot more mischief than I did but got caught far less often. Eventually, he became much wealthier than I am. He made me crazy!

But he was also my mentor, my protector, my sidekick in silliness, in sarcasm, and in secrets shared only by brothers and sisters. He was my best friend. And, because we were only thirteen months apart in age, we had many mutual friends growing up and regularly “hung out.”

Then life moved on and, for many years, every time we would see each other, our visits included my two children, my mom, and my aunt. We would either all arrive at Michael’s house, or descend upon him on his holiday trips home. About three years before his death, I remember well a phone conversation with Michael. He said, “It occurs to me that in all of our adult lives, we’ve never spent time alone together. Melissa, you travel in tribes!” That was enough motivation to decide that, from that point on, each month I would go to the city by myself for a long weekend.

It was during those years that we spoke about his being HIV-positive and the effect it had on his life. Michael lost so many of his friends to AIDS. I remember his saying that the death of friends was no longer an event; it was a way of life.

By the mid-nineties, Michael and others who were HIV-positive were spared because of the introduction of protease inhibitors. But I don’t think many people realize the psychological effects that came with the “lifting” of a death sentence. As Michael explained, he and many of those he knew had prepared themselves to die. Many of his friends had left their jobs. Some sold their homes. Now what? He said first came the euphoria of thinking that you will live to be 80, and, eventually, came the settled reality that, no, death won’t be imminent, but it will come. And, there was this existential struggle—those who were spared realized that if those they loved had survived just a few months more to receive the initial medical treatment, they, too, might have survived. Why them and not the others?

In the last ten years of his life, when, incredibly, Michael found himself quite wealthy because of becoming part of the corporate world (something he considered heresy while at Yale!) he was extraordinarily generous—to our family, to his friends, and to so many people and organizations he knew needed help. He gave and he gave and he gave. He gave his time and talents. He gave his money. He gave away well over half of his fortune, more than ten million dollars. Michael hated recognition and, unless he knew his name would leverage more support from others, he insisted on anonymity.

After his death, though, I and the other trustees of the Michael D. Palm Foundation were delighted to give support in his name. Classical Action’s Michael Palm Series; the Palm Center for Public Policy at UCLA; and the Michael Palm Basic Science, Vaccines and Prevention Project at Treatment Action Group are testaments to Michael’s passion for fighting for human rights and battling AIDS. Through the generosity of Michael’s dear friends, Steven and Judy Gluckstern, the Michael Palm Theater in Telluride, Colorado honors Michael’s love and support of the arts.

It is on Sunshine Mesa in Telluride that Michael’s ashes are spread. As his little sister, who never got the last word while we were growing up, I like to imagine that those ashes are swirling every time someone walks by “The Palm” theater and pauses at the plaque with his bronzed image.

When I was six years old, I began sashaying and belting improvised gospel tunes. My first grade teacher asked my mother if there had been a change at home. “Well,” my mother confided, “her Uncle Mike took us to see the Broadway musical Black and Blue.”

So began the arc of influence Uncle Mike had over my young life. Every Christmas Eve, Uncle Mike would visit Reading, Pennsylvania for one night, and, like a laid-back, cosmopolitan Santa, he would doze in my grandmother’s chair as I unwrapped his gifts, which included things like fuchsia feather boas. When my family visited him in New York City, he’d take us to the Philharmonic, or we’d sit and listen to him play the piano. He’d buy me outrageous clothing at Anna Sui and treat us all to dinner at upscale Italian restaurants.

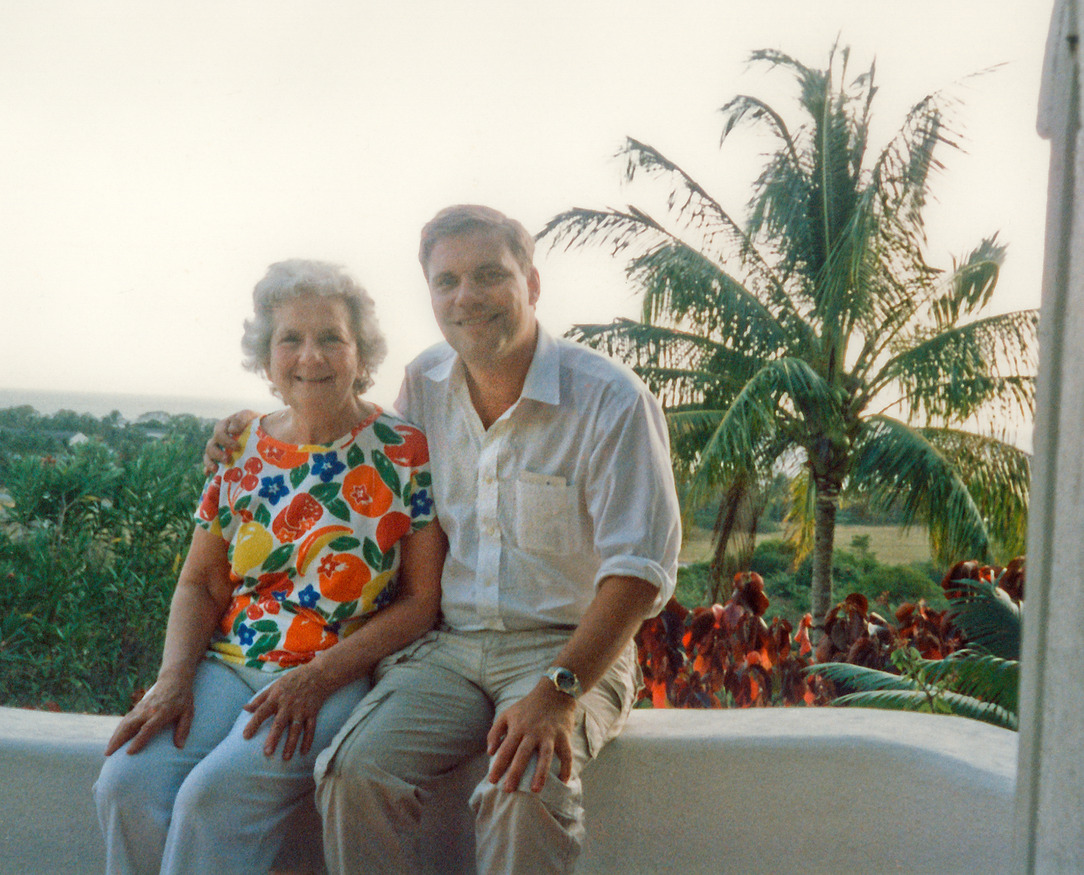

In the summertime, his company jet would set its course for Reading, where our family waited with beach bags. Once aboard, we’d spend the next several hours catching up with Uncle Mike, playing games, and watching the tiny airplane on the radar screen getting closer to my uncle’s homes in Barbados, Bermuda, or St. Croix. Occasionally, I would be allowed to sit in the jump seat of the cockpit during landing. Needless to say, every little child should have an Uncle Mike.

Uncle Mike’s warmth deepened as I grew older. When I was a high school freshman, he made a special non-Christmas Eve trip—the only one I can remember—to see my lead role in the school musical. As the stage curtain opened on an auditorium of faces, I wondered if my efforts at channeling Marilyn Monroe from Some Like It Hot were adequate. The next day, my mom told me that when the curtain rose and I began singing, Uncle Mike asked, “Where did she learn to do that? She is imitating Marilyn perfectly.” My confidence soared.

That summer, I was a “hot box girl” in a production of Guys and Dolls. My mother had been unable to attend the show at the last minute, and when I saw her, I knew something was terribly wrong. She sat me down on our couch, held me, and told me Uncle Mike had died from AIDS-related complications. The look in my eyes must have contained another question, because she continued, “He was also gay, honey.” I learned that Uncle Mike’s exhaustion during his previous Christmas Eve visits was really caused by his fatigue from medication cocktails. My brother and I were never explicitly told what was going on, so as not to sicken my grandmother with worry. My mom carried this tremendous secret for many years.

There was a memorial service at Lincoln Center, where the pianist Earl Wild—my uncle’s dear friend—performed in his honor. The following winter, I was seated in his gorgeous New York City apartment near Lincoln Center with an intimate group of his friends, hearing the sopranist Cecilia Bartoli sing to a rapt audience. Classical Action had planned the concert before my uncle died, and everyone agreed it would be healing and inspiring to hold it posthumously. It was that night in his apartment that I realized what an extraordinary man he was.

Michael and I first met in Tehran in 1976. I had just been recruited to be principal of an English-speaking elementary school, and Michael had been recruited to head the high school’s English department. We arrived in Iran on the same day, but as it turned out, neither of our apartments was ready. After five intensive days together in the headmaster’s house along with my wife Judy, Michael and I had instantly become best friends, and there was something quite magical about how our friendship developed. Michael was incredibly smart, and he had a wonderfully wry sense of humor. Michael’s private time was always very much his own, even when we lived together in the same house. Music and reading fueled and nourished him.

Michael and I were 26 when we started “scheming” in business. A lot of American companies were coming to Iran, for example, to build copper mines in the desert or oil refineries on the southern coast. With a third partner, Chuck Byrd, Michael and I began to explore the idea of how to help these companies educate their employees’ kids and create schools in remote parts of the country. We founded an educational consulting firm called Gluckstern, Byrd, and Palm. Eventually Michael, Judy, and I moved to Athens while Chuck stayed in Tehran.

In Athens, Michael and I turned out to have a lot of downtime. We made it a daily practice to play a game of Scrabble. Embarrassingly, in the over three-hundred times we played, I never once won. Eventually Michael and I decided to make a game of getting the highest combined score—competition morphed into collaboration. Sometimes these games would go on all day as we drank ouzo, a Greek licorice liquor, and strategized to come up with elegant letter combinations to get the highest score, sometimes requiring a nap afterwards. Some would say that was the start of our business partnership. Judy would come home from work, and she would smile at us, knowing what we had been up to.

Michael later joined the Bank of Boston, where he was involved in lending in Africa. He had earned “international credentials” as our business had taken us across the globe. Knowing Michael, he probably convinced the Bank he was personal advisor to the Shah! Michael had the uncanny ability to appear as he wanted people to see him, a chameleon of sorts, and could play any role he wanted to. He was not necessarily “interested” in business, but he understood it to be the means to a philanthropic end.

The process of raising money for Centre Re took us almost a year. We were two guys with less than a year and a half of experience between us, trying to raise $250 million dollars (which was a staggering amount of money in 1987) and Warren Buffett had already passed on the idea. We knocked on a lot of doors, and a lot of people said, “You’ll never get it done.” But Michael and I figured out quickly what roles to play, and importantly, how to make each of us better. While I would be firing out five ideas a minute (many of them half-baked and ill-formed) for a client in a meeting, Michael would sit with his eyes closed, seeming to fall asleep . . . At just the right moment, he would open his eyes and give a very rational, thought-out perspective and identify the best idea. He was comfortable and happy working in the background, but his mind was always operating at high gear. We were the epitome of 1+1 equaling 5.

In 1977, I moved to Athens with Michael and Steven so they could continue building their educational consulting business. For the first few months, Michael slept on our dining room floor. We later bought a little Volkswagen, and on the weekends we’d drive out to Piraeus to dine on the harbor. When we would pick up Michael for dinner, he would often be doing some “light reading,” something like The 10 Greatest Chess Moves. There was an elegance to Michael’s thought process—not a lot of wasted motion.

Steven and Michael had lost all their Iranian business in the late seventies when the Shah fell. Michael had no MBA, but he got himself a job at the Bank of Boston, heading their African lending bureau. Michael would leave us incredulous with his stories about his travels in Africa, which often hinged on the importance of learning how to say in every language, “Where I come from, this is not illegal.”

When Michael moved to New York in the early nineties, he and Steven started renovating a warehouse on Thompson Street—the plan was to have Michael move into one-and-a-half floors, and Steven and I would have the other floor and half. In the process, construction workers hit a water main and the basement flooded. Michael sent Steven a bill for scuba divers he had hired to turn off the water leak. Michael made sure an enormous elevator was included—one of the largest elevators in New York proportional to the size of the building—in order to comfortably move his pianos.

During construction, Michael had started to get really sick. It became obvious that he wasn’t going to be able to move to Thompson Street. He was spending more and more time with Classical Action and at Carnegie Hall, and he moved to the Alfred across from Lincoln Center and began to host concerts. His pianos had to be transported on top of the elevators.

Michael gave away much of his money to institutions—most of it anonymously—but he also supported friends and street artists. We found out after his death that he had paid for many of his friends’ medications—friends who had no insurance and couldn’t afford protease inhibitors. When we realized this, after his death, Steven and I continued to fund some of the medication. Michael did a lot very quietly.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

Michael and I met when I was in Berkeley College and he in Silliman; I had just started playing volleyball as a junior. He was the volleyball captain and guru—our coach on the field. Since we were a club and not a varsity sport, we had much more freedom in how we managed ourselves. We ended up getting Yale’s discarded fifties-era basketball uniforms and jazzed them up with bright, multicolor striped knee socks. We were not encumbered by convention!

Senior year, Michael and I moved into a house on Howard Avenue with three other roommates. It was like family, and we all learned to cook for a crowd. He had a hand-me-down Mercedes from his father, and I had a 1965 Dodge Dart to drive our friends around. We had a piano in that house, and I realized he was a fantastic pianist. We spent many hours with our friend, Antoinette Van Zabner, who was a graduate student in the School of Music and also became really close with Michael. They had raucous discussions about music. Michael was into anything from classical to heavy metal.

I never saw Michael date anyone, and I never knew Michael as gay. I suppose this speaks to the naiveté of the seventies: We were 21 and worried about civil rights, Nixon, and Vietnam. We pooled together “Greyhound funds” to send those who had the least favorable numbers in the draft lottery to the far corners of upstate New York or to Montreal. If there was a gay association on campus, it was certainly not publicized as it is now.

We were in close touch following graduation and spent part of that summer at Cinnamon Bay on St. John in the Virgin Islands. We camped for $11 a night, ate Cheerios, went to the beach every day, and tried not to get sun poisoning. I went off to medical school in the fall, and Michael went to Harvard graduate school in comparative literature at a time when the world seemed to be falling apart.

I was one of the lifetime beneficiaries of Michael’s generosity—he spoiled his group of friends and family, flying us from house to house on the company jet. On the other end of being sweet, though, Michael had a mischievous tongue. For example, once we sat down to dinner at a restaurant. When the waiter apologized for not having the 1972 Pétrus wine in stock, Michael turned his eyes to the ceiling and exclaimed, “Ah, what do the miners of South Africa know of suffering compared to this?” It was mortifying! People who didn’t know him would be floored, and we would just shake our heads, chuckling. That was the exactly the reaction he was looking for.

We went to Italy on vacation and Michael was a wonderful guide—he had a sharp eye for art. At the Cornaro Chapel in Rome, we saw the Bernini sculpture of St. Teresa in Ecstasy; Michael tried to imagine what sexual act was causing her ecstasy. We visited San Pietro in Vincoli, where the chains that bound St. Peter are housed. At the sight of the chains, Michael and our friend Jerry fell to their knees, crawling towards the altar and proclaiming their devotion. Behind us was a group of Polish pilgrims, who, upon seeing Michael and Jerry, followed suit and also started walking on their knees towards the chains. Meanwhile, Michael and Jerry walked out the side door, laughing. At another church, we got kicked out by the clerics after Michael and Jerry propped themselves up on the tomb of a Pope for a photo. At another church, they threatened to steal a whole plate of communion wafers and top them with Cheez Whiz to sell for religious fundraising. A lightning bolt could have struck us down at any time.

Michael didn’t want to be classified: not as a gay, not as a financier, and not as a saint. He didn’t believe in taking any of his roles too seriously. I was aware he loved his colleagues, but he never explained his business to me. He would roll his eyes and say, “All this reinsurance is too intensely boring for you.” Work was work, and he chose how to spend his time outside of it.