I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

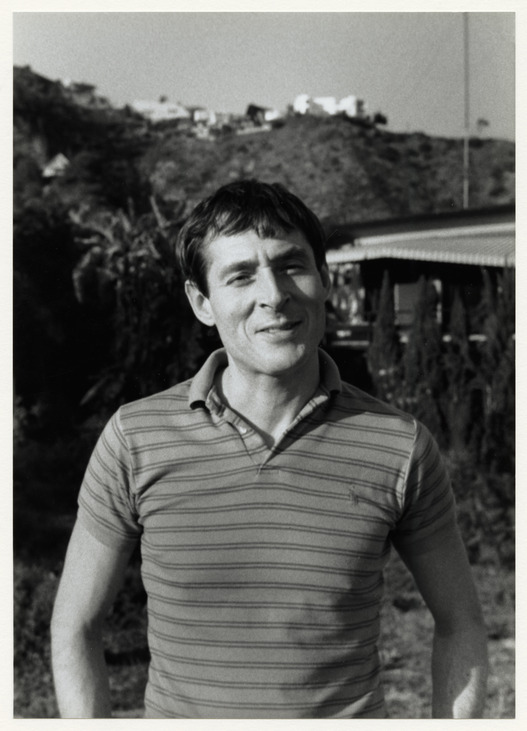

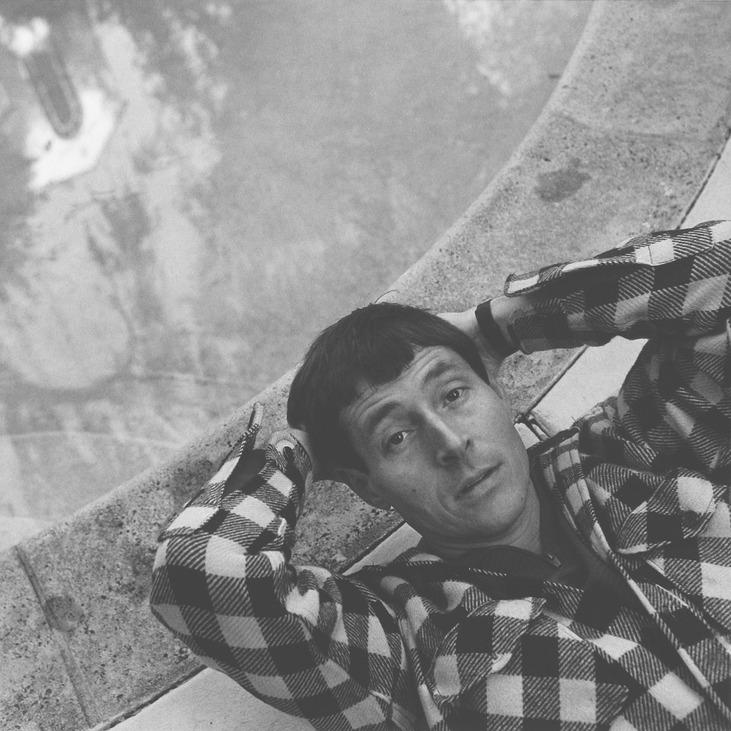

Paul Monette was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1945. A respected author and poet, Paul wrote thirteen books, or “glib and silly little novels” as he called them, before he died in 1995 at the age of 49.

Paul attended Philips Academy in Massachusetts before arriving at Yale in 1963. He was a member of Jonathan Edwards College, served as the editor of a number of Yale literary publications and, in his senior year, was the Class Poet and a member of Elihu, a senior secret society. Throughout his time at Yale, Paul remained conflicted about his sexuality, and told no one—not even his secret society friends—about his attraction to men.

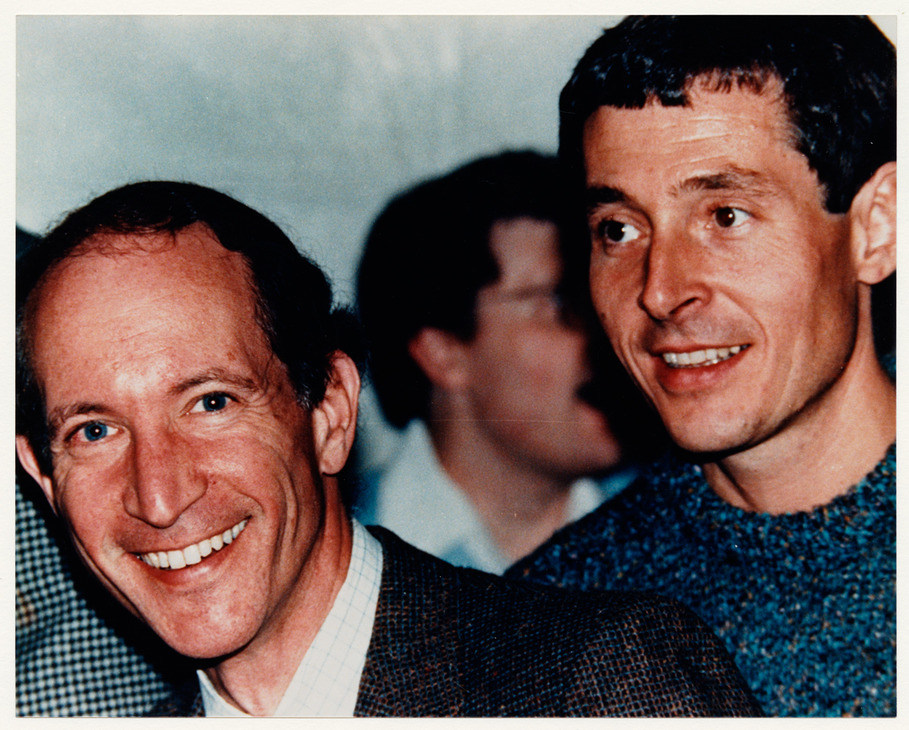

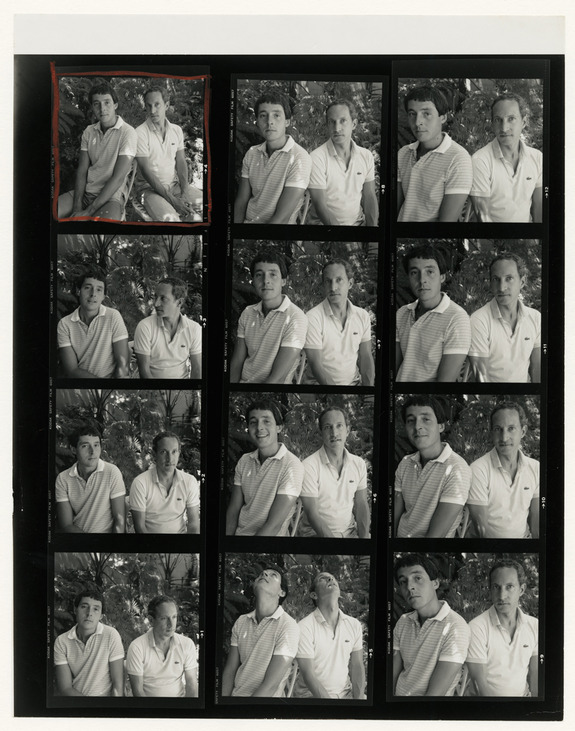

It was not until 1974 when Paul met lawyer Roger Horwitz that he began to accept his sexuality. After several years teaching literature at Milton Academy and Pine Manor College, Paul and Roger moved to West Hollywood where Paul started to explore his gay journey through writing novels, many of which featured gay protagonists.

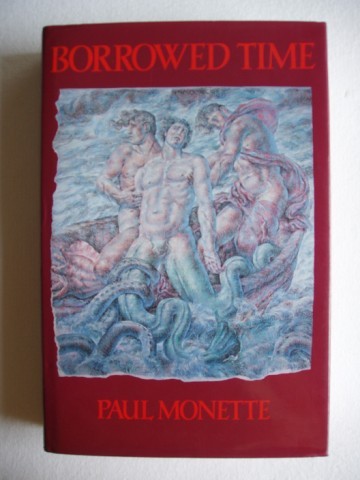

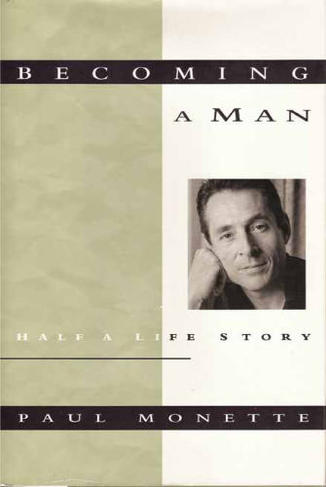

The pair lived together in Los Angeles for 10 years until Roger died of AIDS-related complications in 1985, an event that had a lasting impact on Paul’s life. He chronicled Roger’s final years in his acclaimed memoir Borrowed Time and in the following years penned a number of novels about the effects of the AIDS epidemic on the lives of gay men. His most praised book, Becoming a Man: Half a Life Story won the 1992 National Book Award and details Paul’s life until he met Roger. In the book, he wrote: “I can’t conceive the hidden life anymore, don’t think of it as life. When you finally come out, there’s a pain that stops, and you know it will never hurt like that again, no matter how much you lose or how bad you die.”

Paul lived another ten years after Roger’s death, spending the last five in Los Angeles with his husband Winston Wilde and their two dogs, Puck and Buddy.

III.

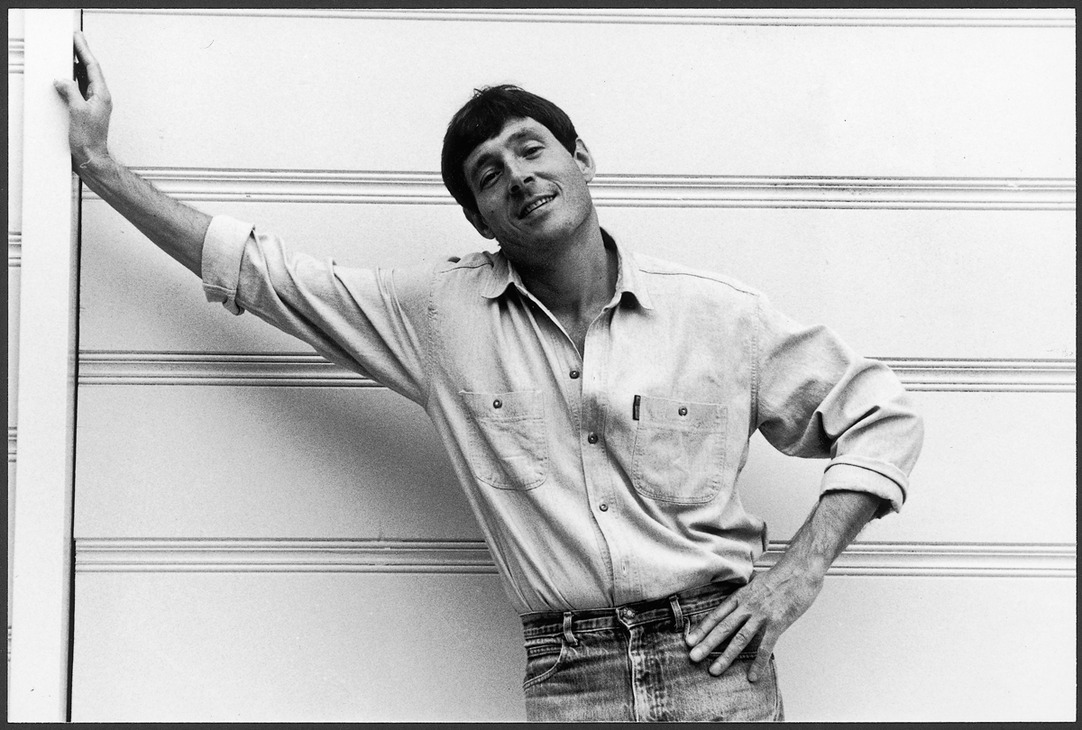

It’s not always easy to say what exactly you miss about a person. Maybe he was the best lover, or cook, or friend. Perhaps it was how he told a joke, or smiled, or could keep a secret. What I miss most about Paul was his intelligence—the gentle but determined way he lit up any room he entered.

Paul didn’t take prisoners like some famous writers do, nor did he suffer fools gladly. He was a dynamic public speaker, but Paul also listened to people patiently and well. It was this profound capacity for caring about what others said, thought, and felt, that was his greatest gift.

It was a singular pleasure to know Paul during his final years. We were both members of a gay and lesbian writing group in Los Angeles, and I can still recall the delicious sense of anticipation we all felt when Paul began to read another few pages from a new work in progress. One day he and I sat down together for a lengthy interview about his inner life; what made him tick as a man and as an author. While not particularly religious, he was in fact a deeply spiritual person. He was in obeisance to the pagan gods of love and beauty, and of the sun. Like the ancient Greeks, he believed God was in the wind.

“It’s been my experience that gay and lesbian people who have fought through their self-hatred and their self-recrimination have a capacity for empathy that is glorious,” Paul once said. Added to that is our capacity “to find a laughter in things that is like praising God. There is a kind of flagrant joy about us that goes very deep and is not available to most people.”

I could not help but think about these words the morning I stood by his gravesite watching the first shovels of earth thrown in. Tears of loss and remembrance were welling up fast, but then I thought I heard a familiar sound. Anyone who ever heard Paul’s gleeful laugh would never forget it. Some people go through life thinking it is a dreadful curse or something that can be abused. Paul loved life and embraced it in as many ways he could. His laughter was always in celebration of that.

“So look, kid,” the voice behind the laugh seemed to say. “Lighten up a bit, would you? You’ve got things to do, so get to it.”

Paul is no longer.

I don’t get to talk to him on the phone. See him at his house. Meet him and Winston for dinner at Hamburger Hamlet. I don’t hear publishing gossip from him. I don’t hear his galloping sentences, prodigious collections of thoughts tumbled together, each breath bringing a new idea connected to the last or to the one before that, and all tied up neatly at the end of one huge run-on sentence. Or somewhere over the course of the evening.

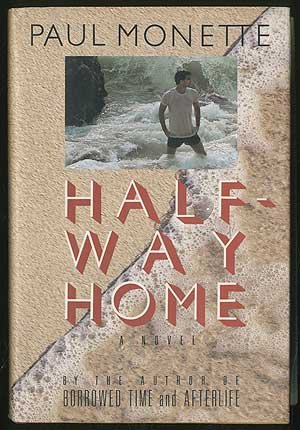

I watched Paul fight for his life. When I first met him, he was writing Halfway Home. He talked about dying; he lived on the battlefield. He was HIV-positive then, counting his days, wondering if he’d live to finish the book—a worry he had expressed in the first paragraph of Afterlife, and again to friends with each subsequent work. Perhaps there were other things he despaired of leaving undone, but I only heard his concern in context of his work: Would he get to finish? Obsessed, possessed, he hurled out his words, challenges to the enemy but also to us. Pay attention. He wrote tethered to his IV, pushing the pole that had been Roger’s from one room to another to write. Halfway Home, Becoming a Man, Last Watch of the Night. Mounds of pills. Gallons, eventually, of infusions over the years.

I worried as he sped through Becoming a Man, afraid he would die when it was done. His life story, the half before Roger. And he’d gotten Winston into it, so maybe he’d finally said everything.

No. He was still fighting. Distracted by the hoopla surrounding honorary doctorates and awards, he started a short piece about his dog Puck. Ostensibly about Puck and Buddy, Winston’s dog, learning to live together, but really about Stephen, and about how we all learn to live with loss. The strength of love.

He wrote that and the other essays in chunks. Gulps more likely, knowing Paul. Submerged in doctor’s appointments and allergic reactions to drugs and just the day-to-day battle with the plague, he’d come up for air—or writing, perhaps the same thing for Paul.

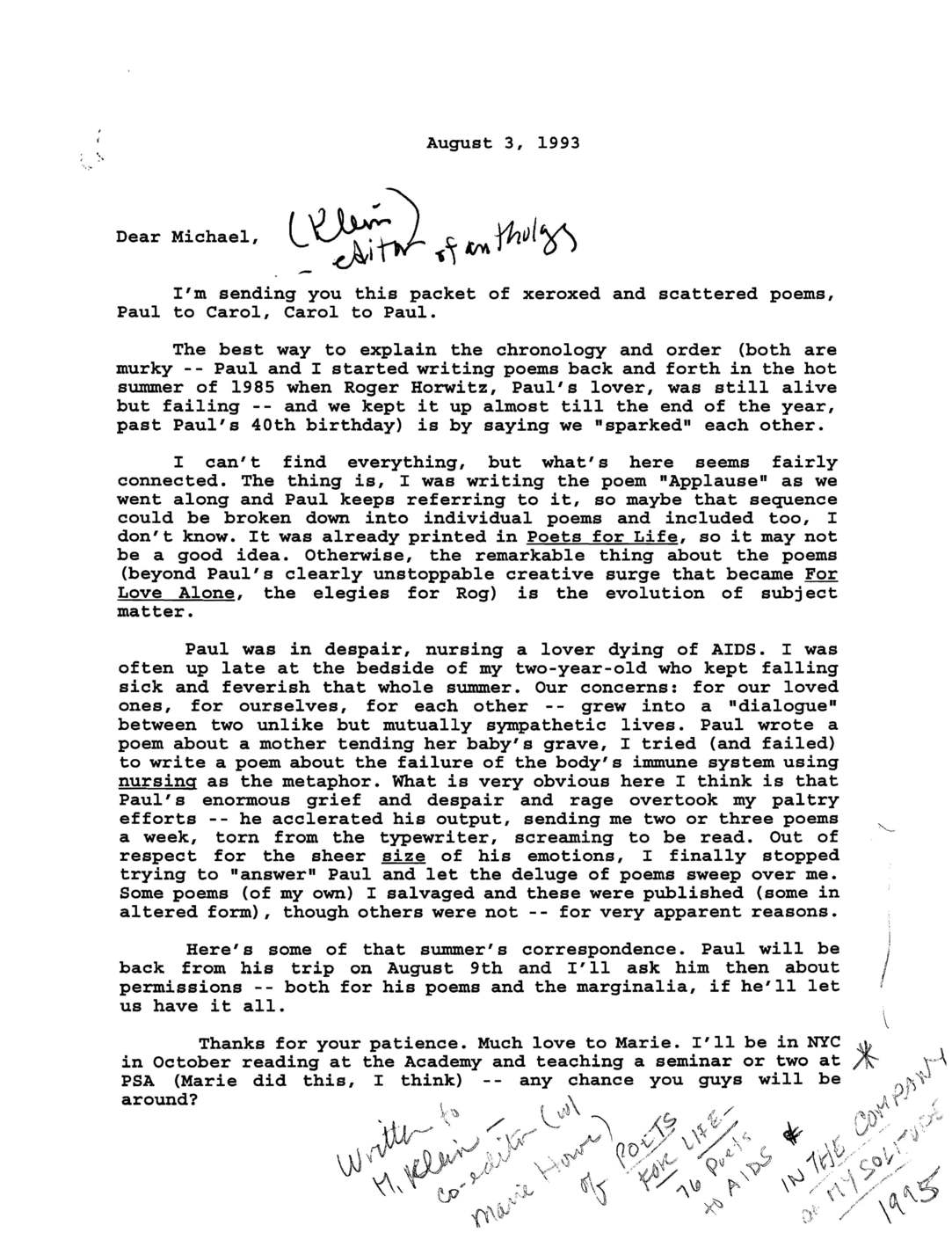

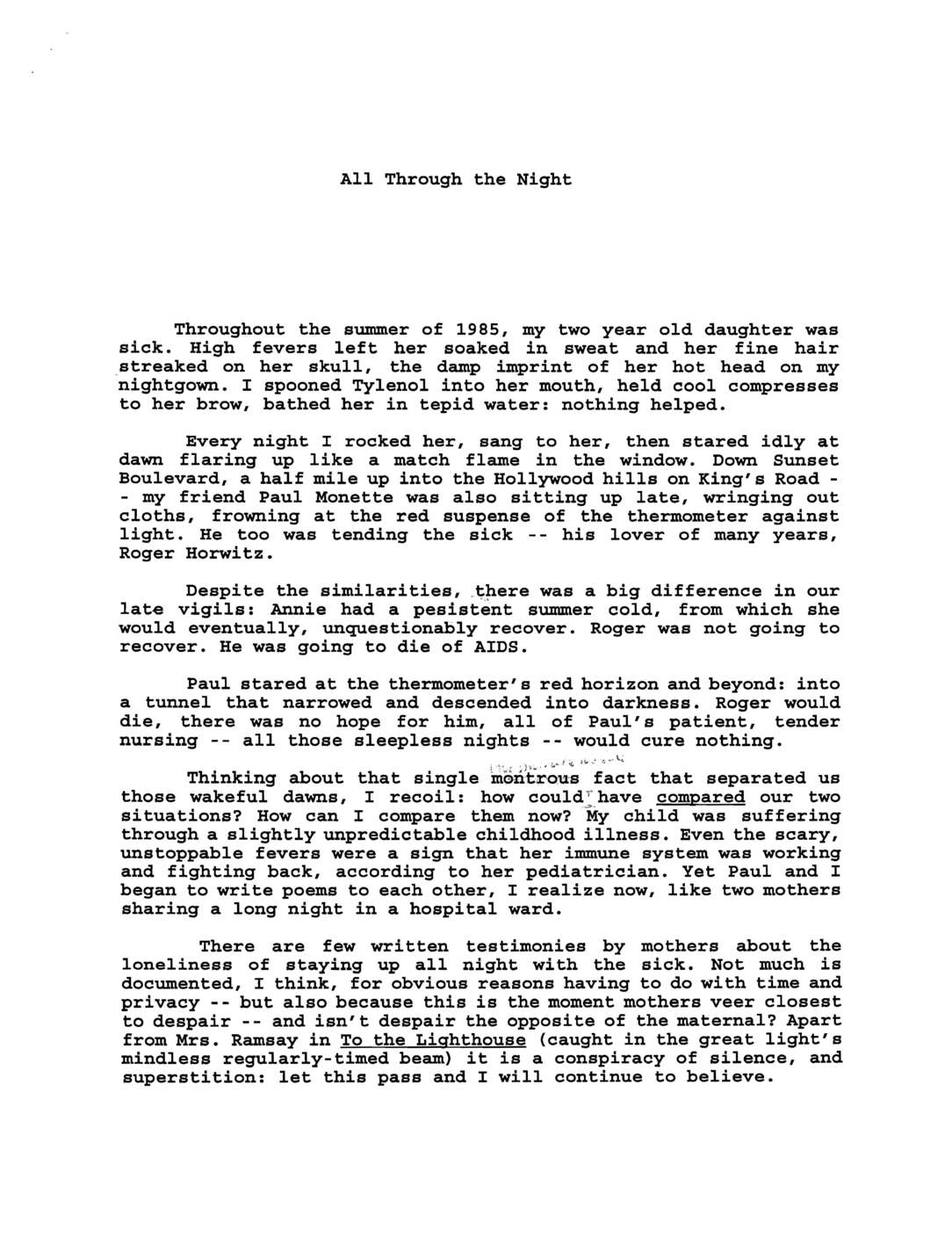

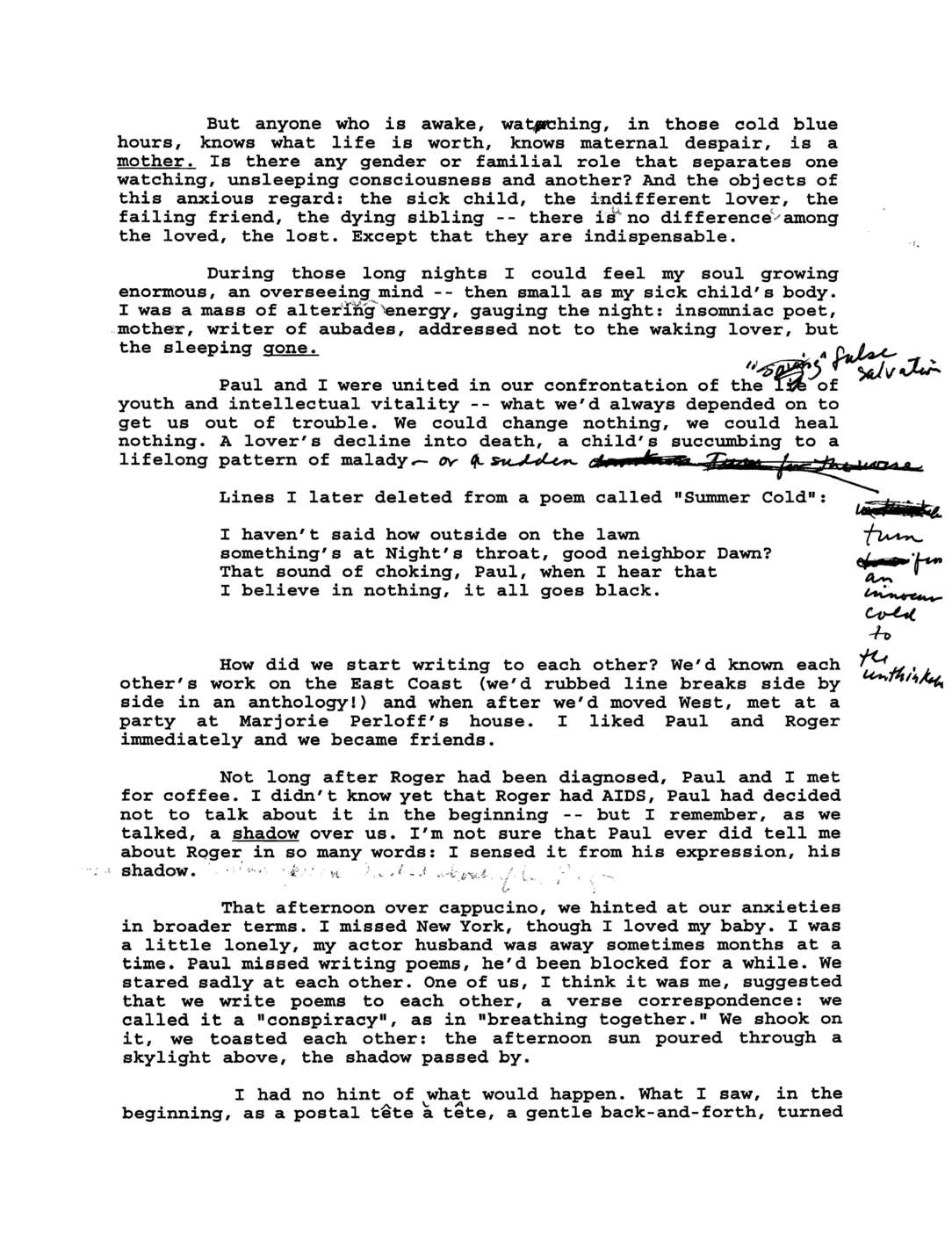

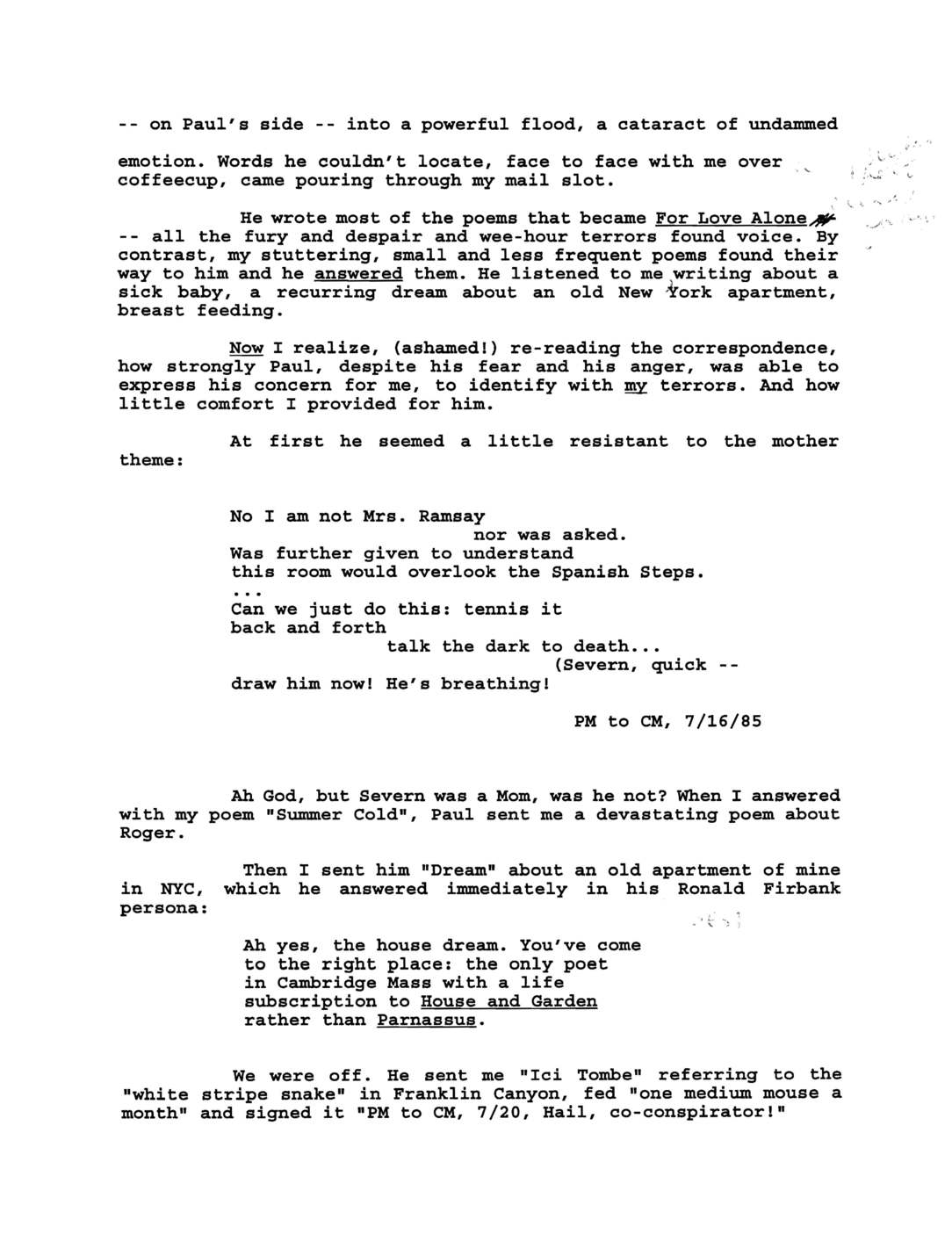

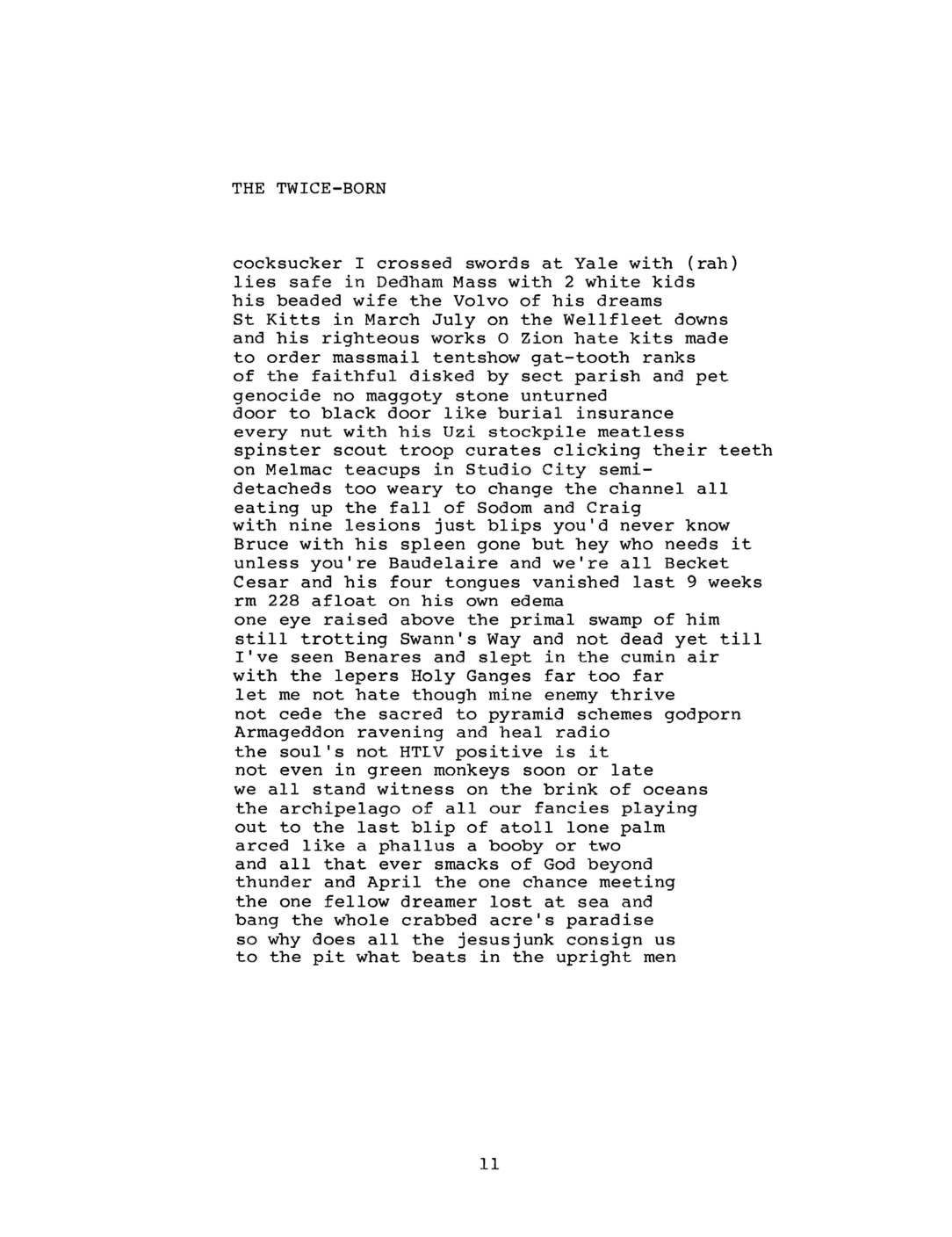

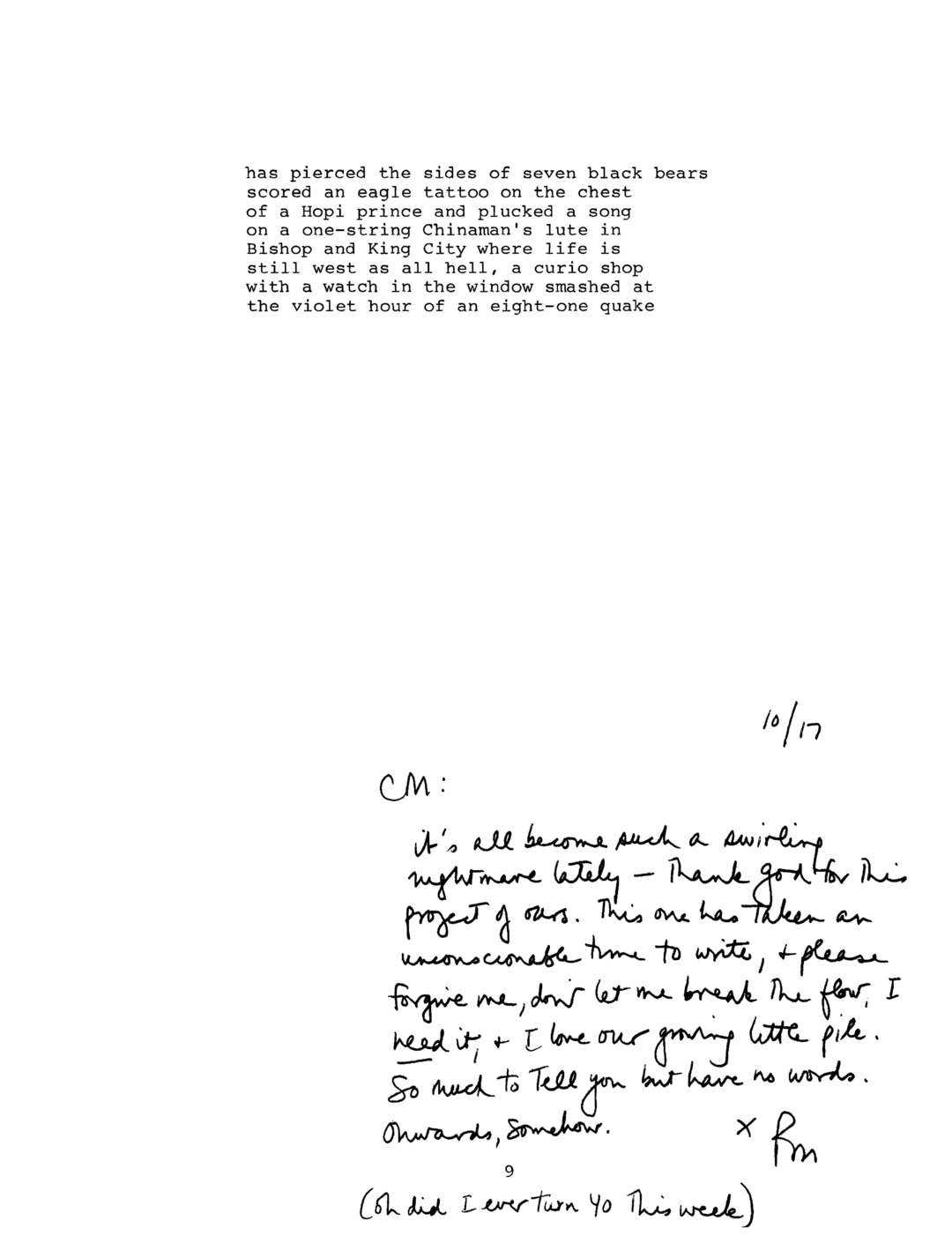

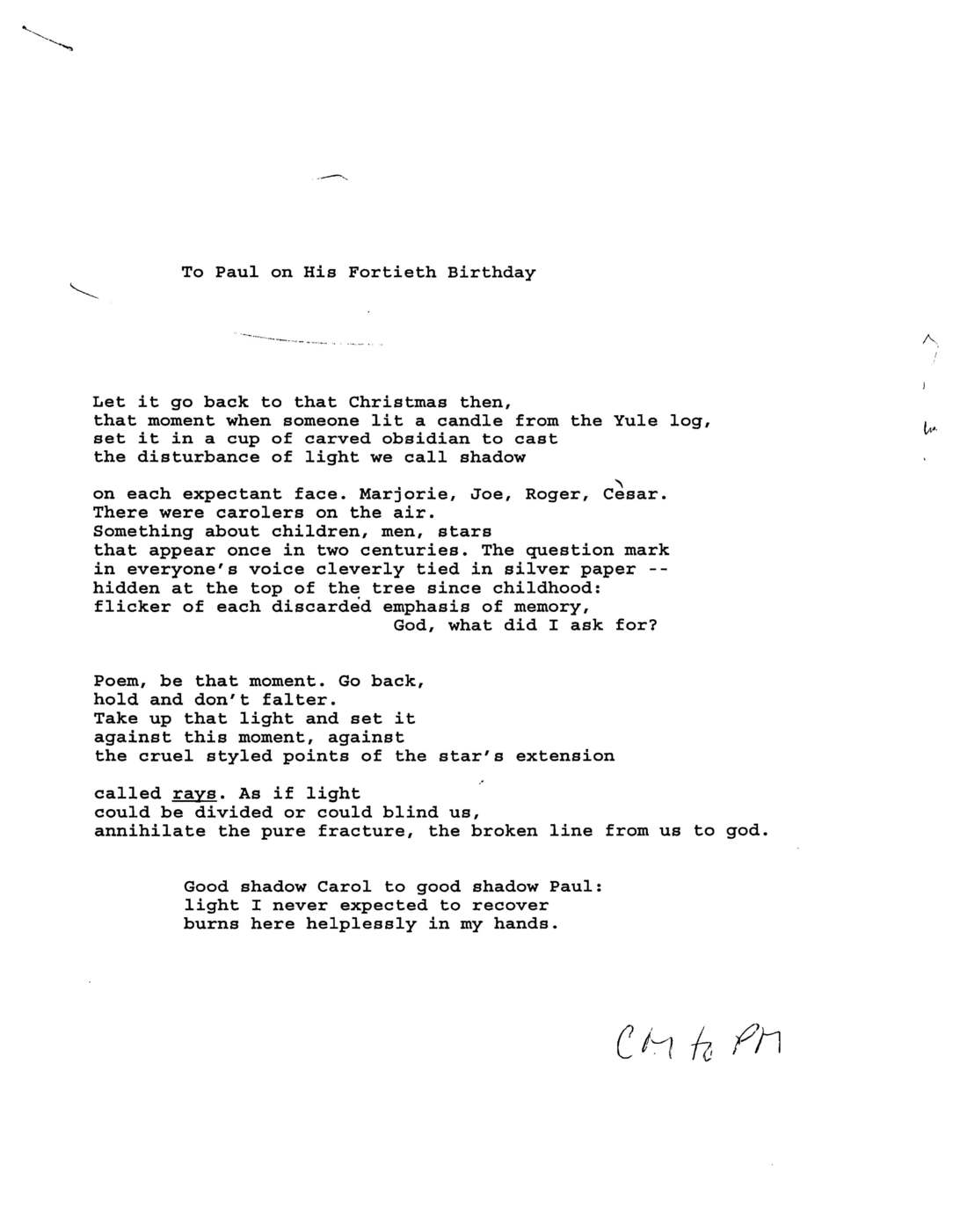

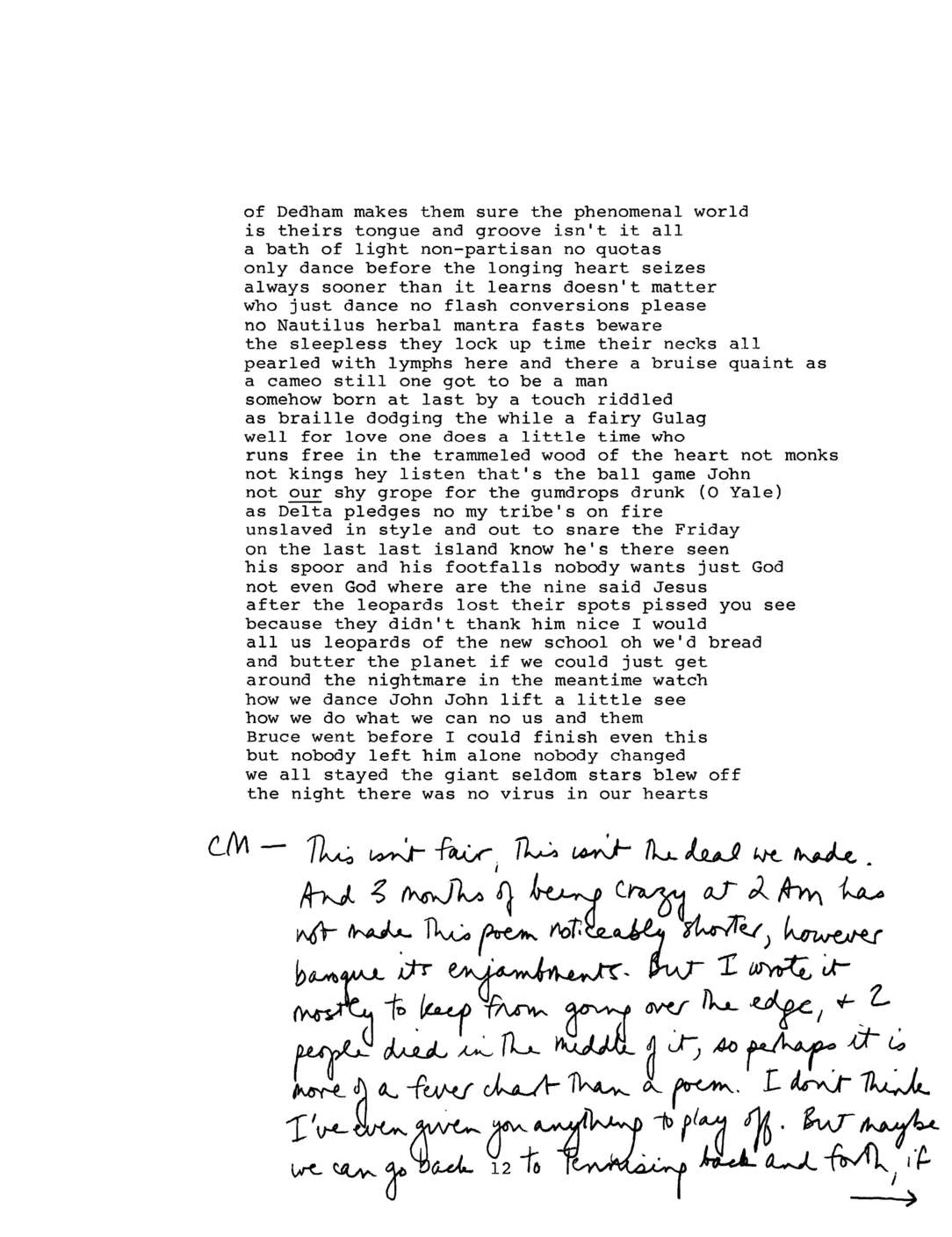

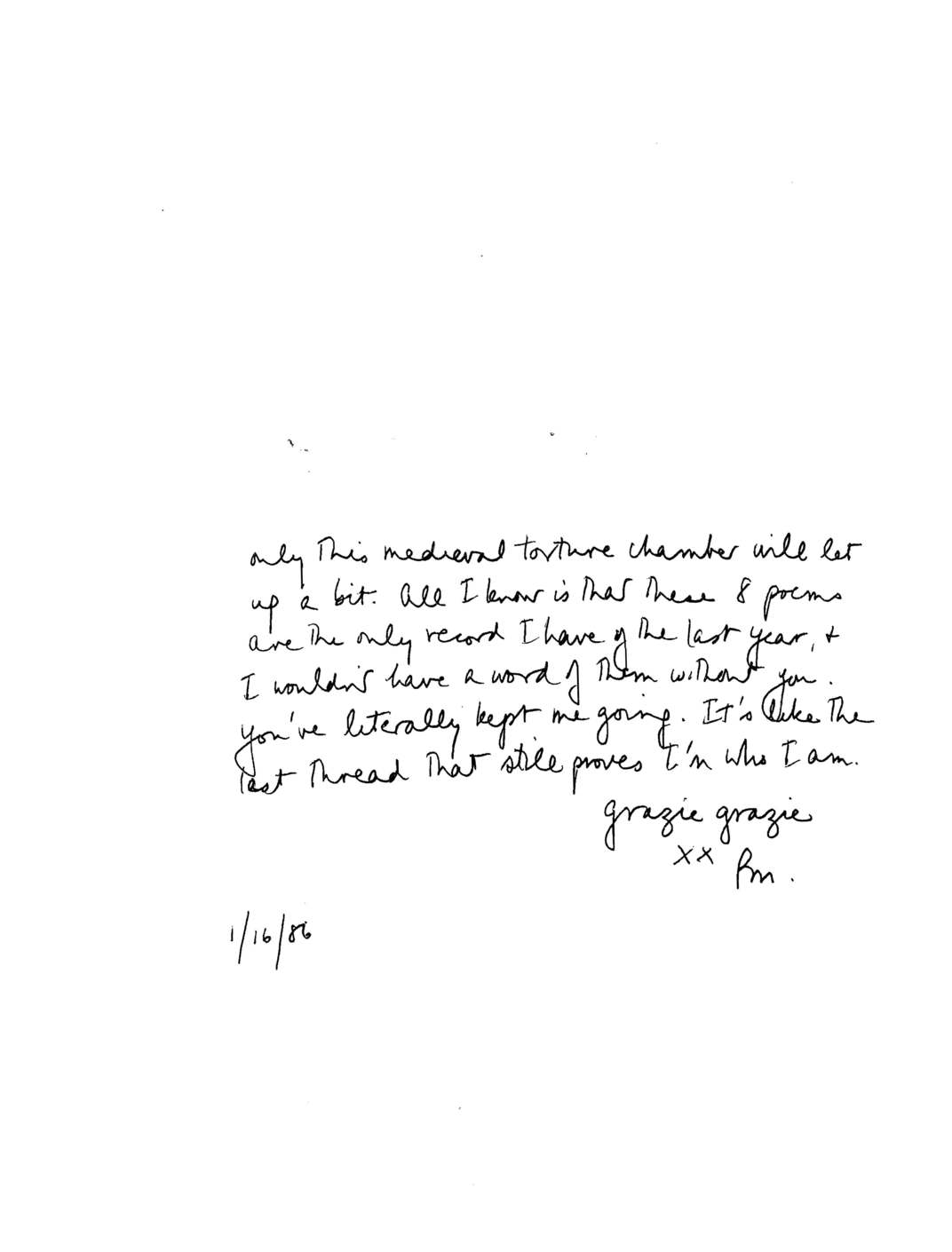

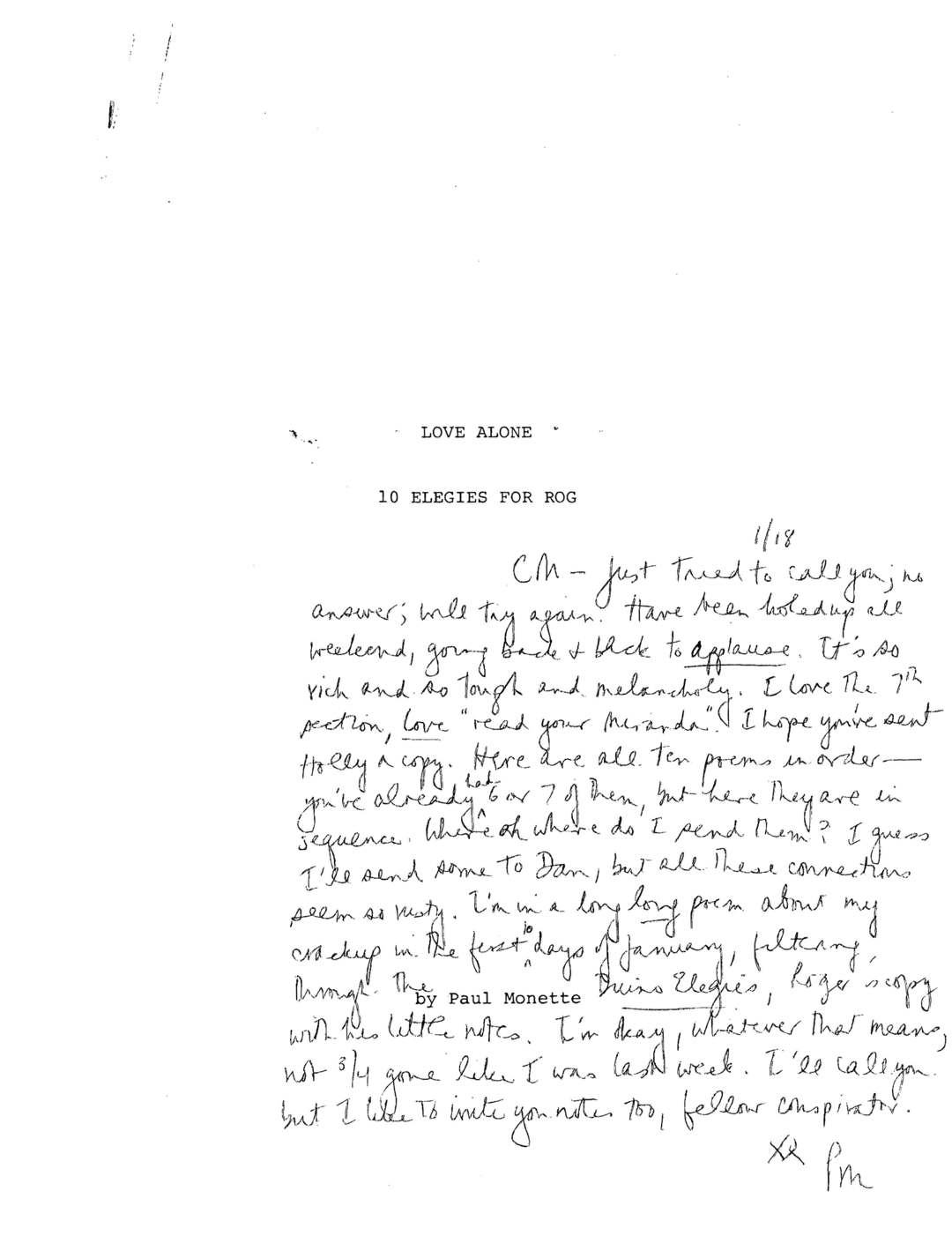

Paul and his friend Carol Muske-Dukes exchanged poems during difficult periods of their lives. The poems and their correspondance is featured in the slideshow below, along with Carol’s reflection on these exchanges.

Paul Monette knew he had a privileged education. In the ninth grade, he left public school to become a day student at the prestigious Phillips Academy in his hometown, Andover, Massachusetts. The stigma of being the local boy on scholarship tormented Paul. As he wrote in Becoming a Man: “The school reeked of privilege and separateness. In the years to come, I would learn the code of the ruling class, how a man with the proper credential went to Andover but didn’t come from there. For a local boy to pass through its iron portals…meant that ever afterwards he would lose his citizenship in the village.” There was no denying that Paul came from there, but he was wanted to go places, and he was determined to succeed.

Prep school for the young Paul was inextricably connected with his emerging manhood, in which he found himself to be failing: “I grew more invisible every day. I buried myself in books.” As miserable as he was at Phillips Academy, though, its prestige allowed Paul to aspire to the Ivy League for college.

He was admitted to Yale, into Jonathan Edwards College. While Paul sometimes disparaged his time at Yale, he did learn a great deal. In particular, he studied poetry with two of the literary giants of the twentieth century, Cleanth Brooks and John Hollander. Paul wrote that he “discovered with growing confidence a capacity to walk through the walls of a poem. The hardest stuff made sense to me. . . I liked being adrift in symbols, beauty for beauty’s sake. When Hollander said the subject of the poem was the poem, I was dazzled. Perhaps after all one could live in the temple of art, feeding on air like an orchid.”

Literature was a consolation for Paul as an undergraduate. As he put it, “Poetry served as a sort of intellectual wallpaper to brighten up the closet.” The alienation that he felt—from himself, from his body, from others—defined Paul up until his late twenties. He didn’t blame Yale, exactly, but he certainly felt as though his experience there hampered him sexually even as it expanded him intellectually.

In the summer before his senior year, Paul won a scholarship to work on Tennyson in England. In London, he met a man and, at last, had a full-fledged adult sex encounter for the first time in his life. Clearly, that liaison brought out all kinds of conflicts in Paul, but it also began the emergence of the gay man in him.

His autobiography at Elihu was another kind of coming out. He didn’t confess his homosexuality, but he did discuss another “secret”— his younger brother Bob, who was severely disabled because of spina bifida. In 2001, I interviewed Jorge Dominguez, an Elihu member who was present for Paul’s Thursday night autobiography. Jorge recalls: “What I remember is the extraordinary emphasis on his family. These were very complex family dynamics, filled with pain. But the stories of his family took up nearly all of the time, so much so that the strongest impression that I remember retaining from that time is that he talked very little about himself. The autobiography was very elegantly constructed. There really was a narrative; there were pauses and flourishes. There was almost sort of a theatrical dimension. Paul was a theatrical person. In the theatrical aspect of the presentation, it was very well thought out, but I didn’t pick up any hints about his sexuality.” Performance was what Paul’s entire education—his whole life up until that point—was about, at least until he began the agonizing, liberating coming out process in earnest about seven years after graduating from Yale.

In Borrowed Time, perhaps the best book we have from inside the AIDS crisis, Paul describes the relationship between Roger Horwitz and himself as “the only Harvard/Yale marriage on our block.” A decade or so after graduating, Paul had made peace with his education. He acknowledged, in the documentary The Brink of Summer’s End, that he’d had “a very decadent education. I was hurting so much inside that I barely took it in . . . . I really didn’t grow very much from the age of 13 to the age of 21. I got all A’s, but I barely understood what that education was for.”

He came to understand it though, as he came to understand himself more fully. His erudition and wit are evident in everything he did. Paul had the talent of a poet and the benefit of a great education, one that enabled him to write some of the best books of the past twenty-five years.

I cannot tell you how much I admire Paul Monette. He was one of very few artists who didn’t run away from facing AIDS. He wrote his and our history of this awful plague in just about every conceivable form—poetry, fiction, memoir, autobiography, television, screenplay—and every word he wrote is heartbreakingly moving. I salute his courage and I salute his grand and noble talent and I salute his magnificent achievement and I thank him for his inspiring admonition to us all: “Work, for the night is coming.”