I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

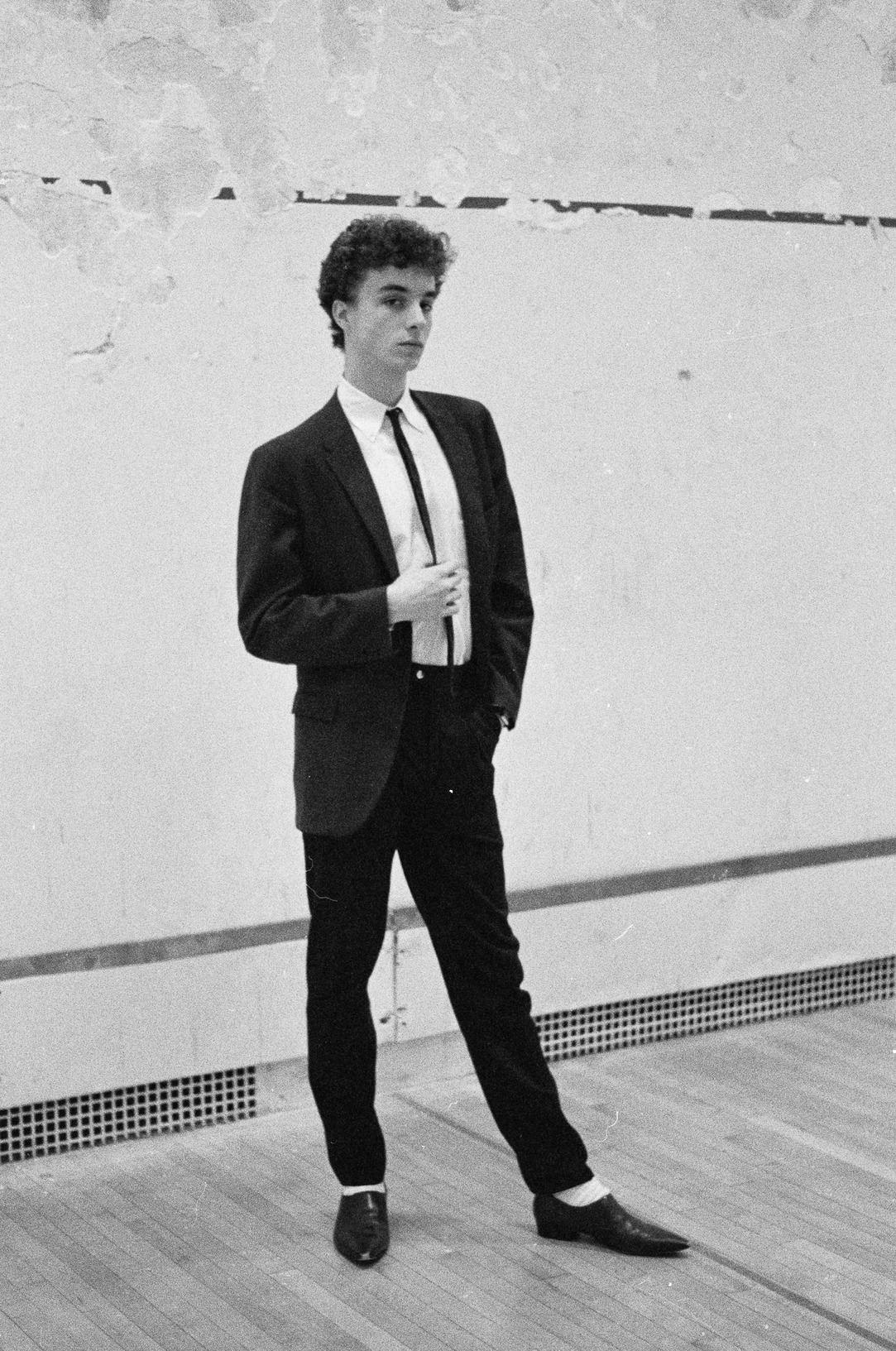

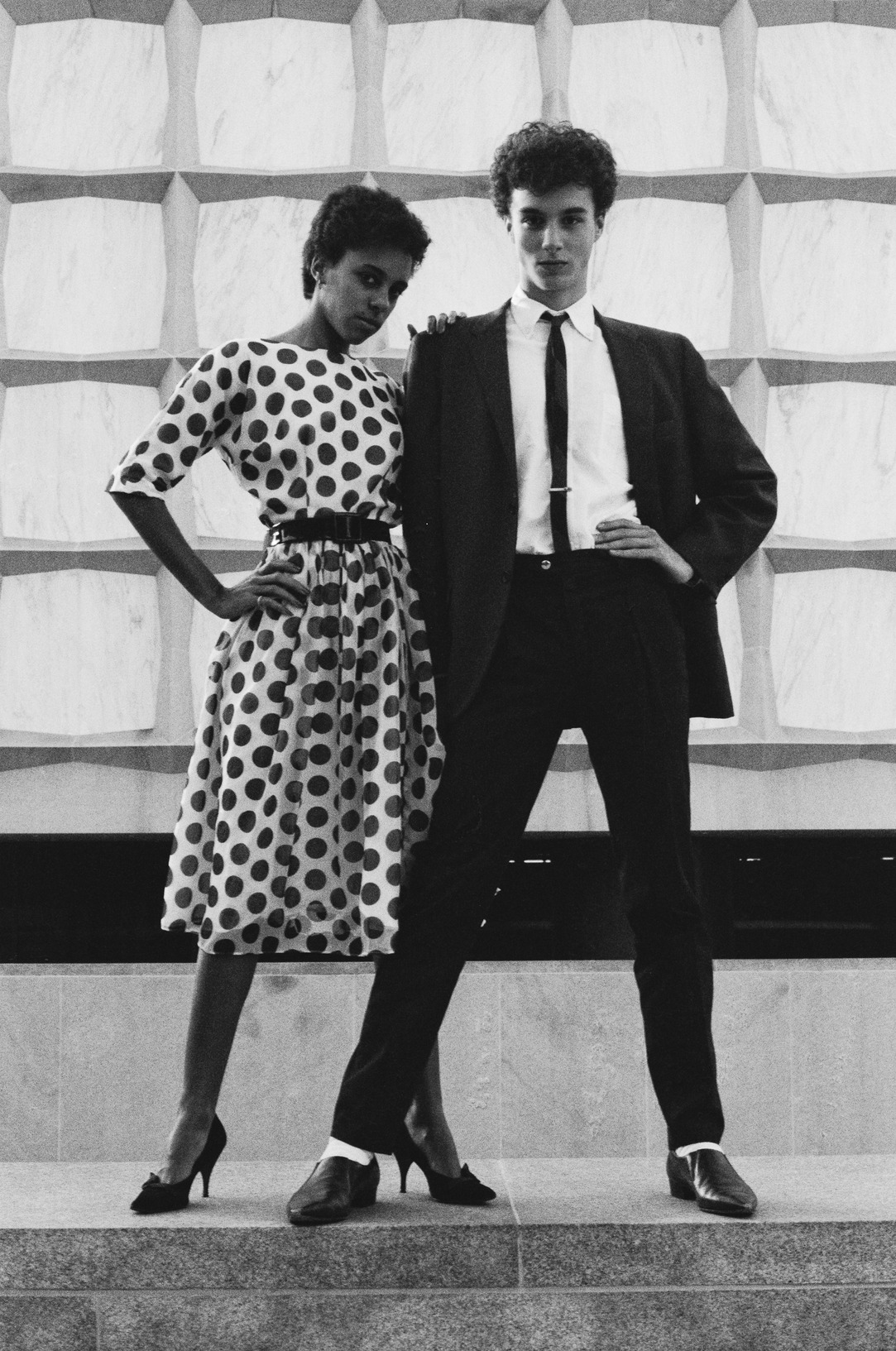

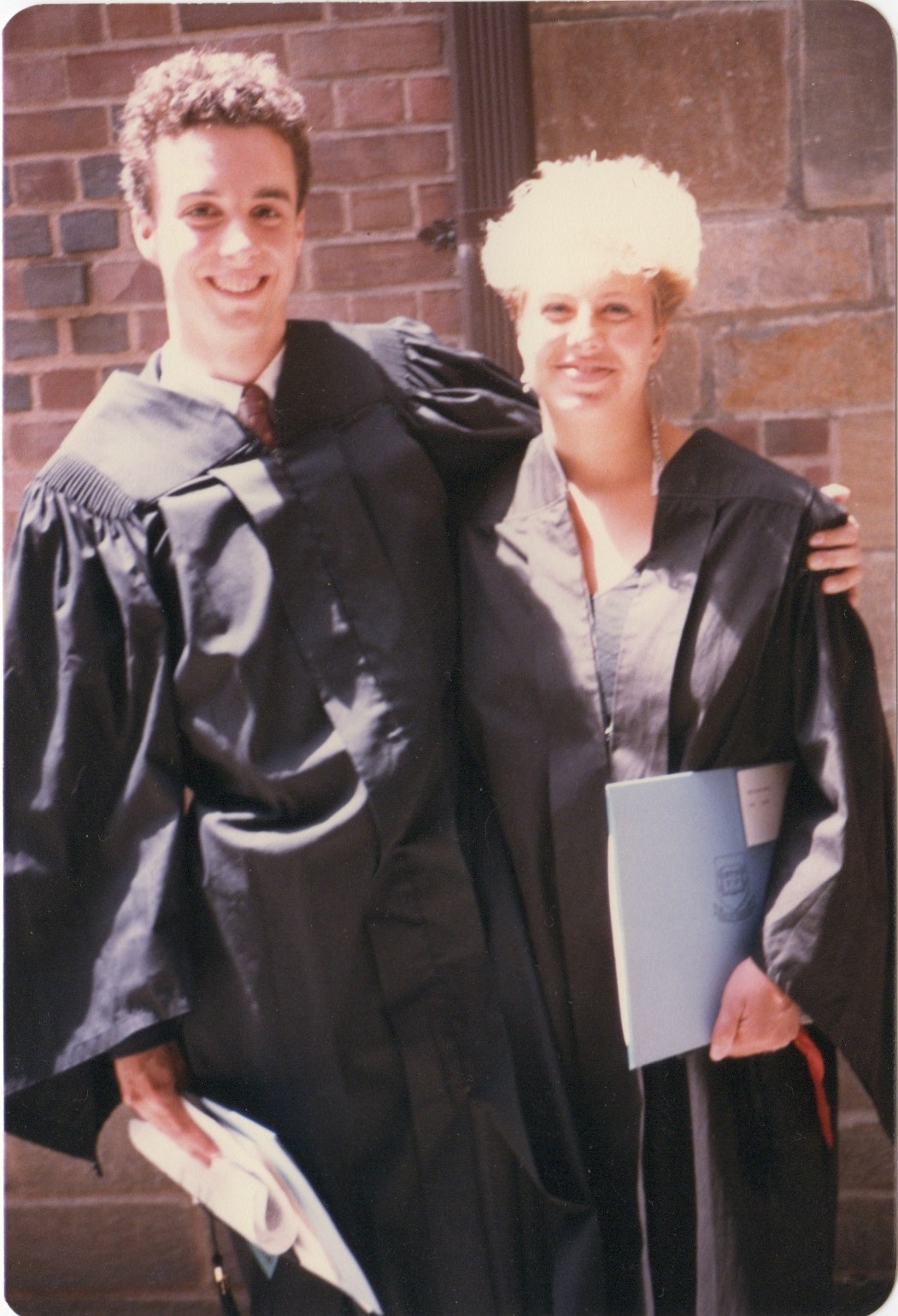

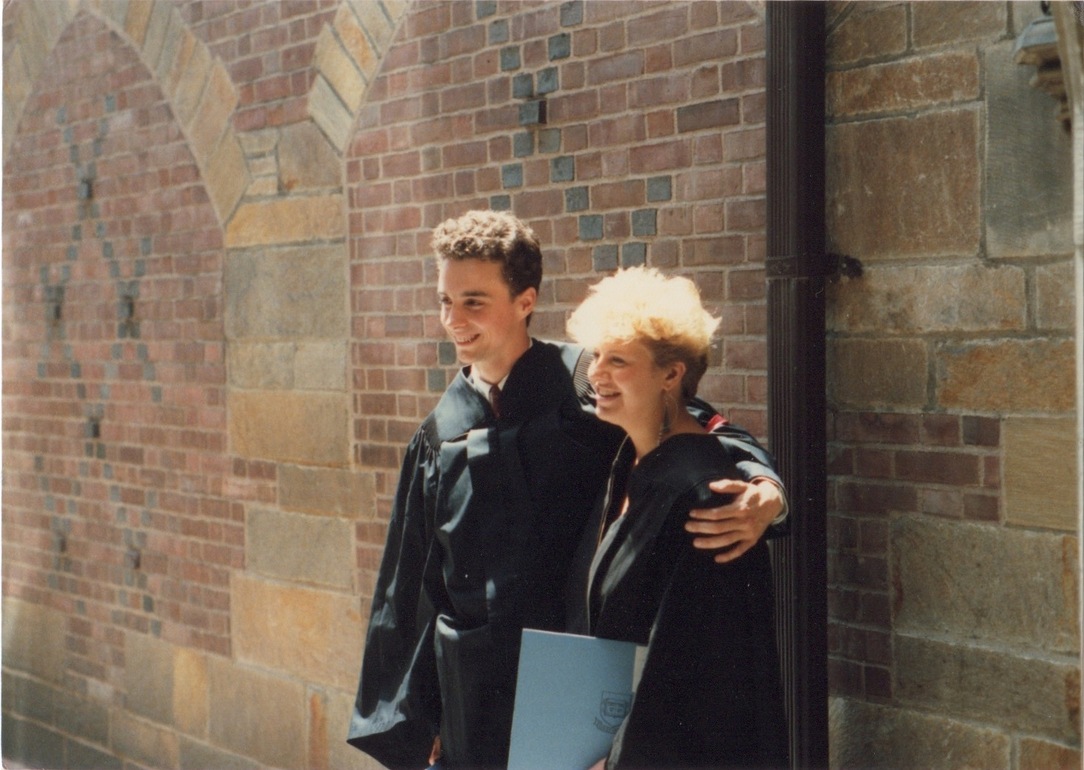

Hugh Auchincloss Steers was an artist born in Washington, D.C. in 1963. Born the grandson of Hugh D. Auchincloss, son of Nina Gore Auchincloss, and the brother of filmmaker Burr Steers, Hugh spent his teenage years attending the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, CT. He then joined the Yale College Class of 1985 as a member of Jonathan Edwards College.

Hugh studied painting at Yale and quickly became an active part of the campus community. In 1983, he studied painting abroad in France and Italy with the Parsons School of Art and Design. His art education continued at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, from which he graduated in 1991;

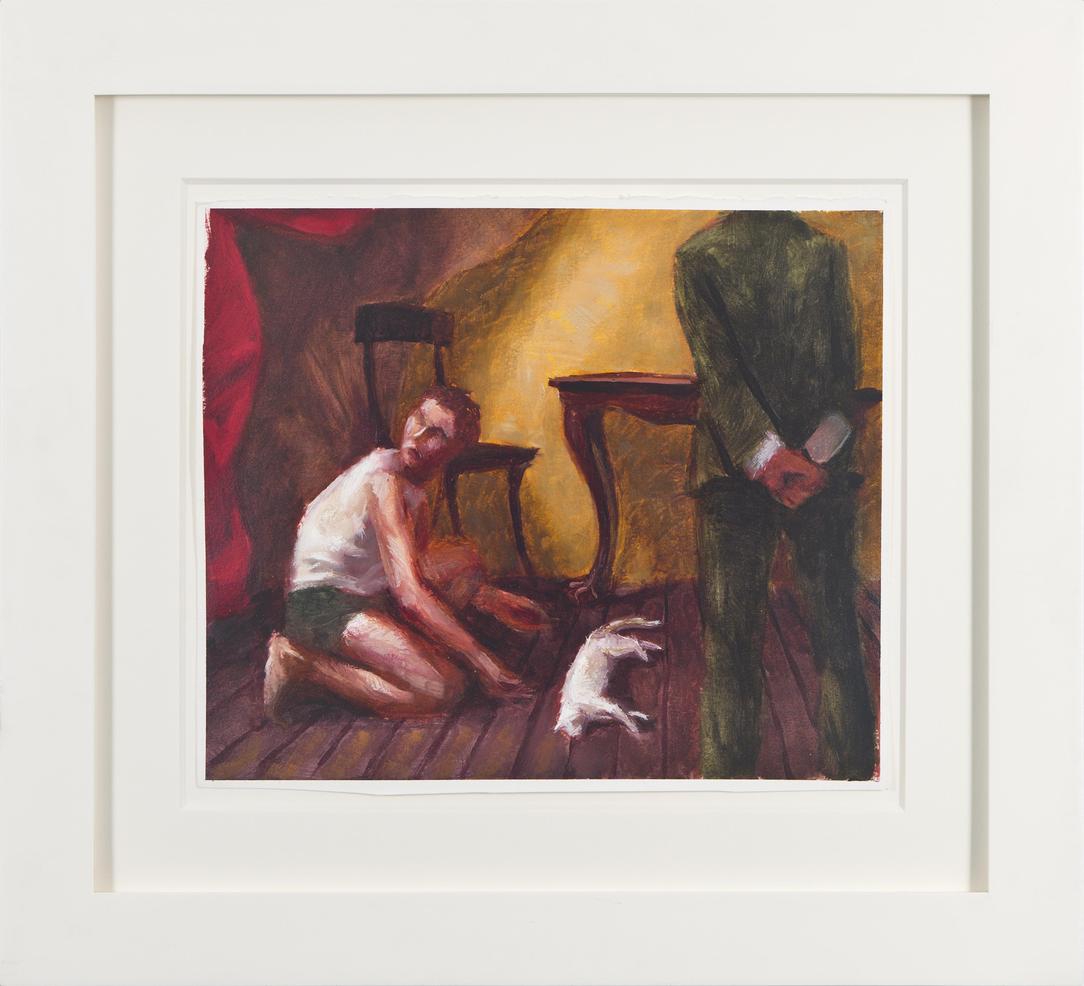

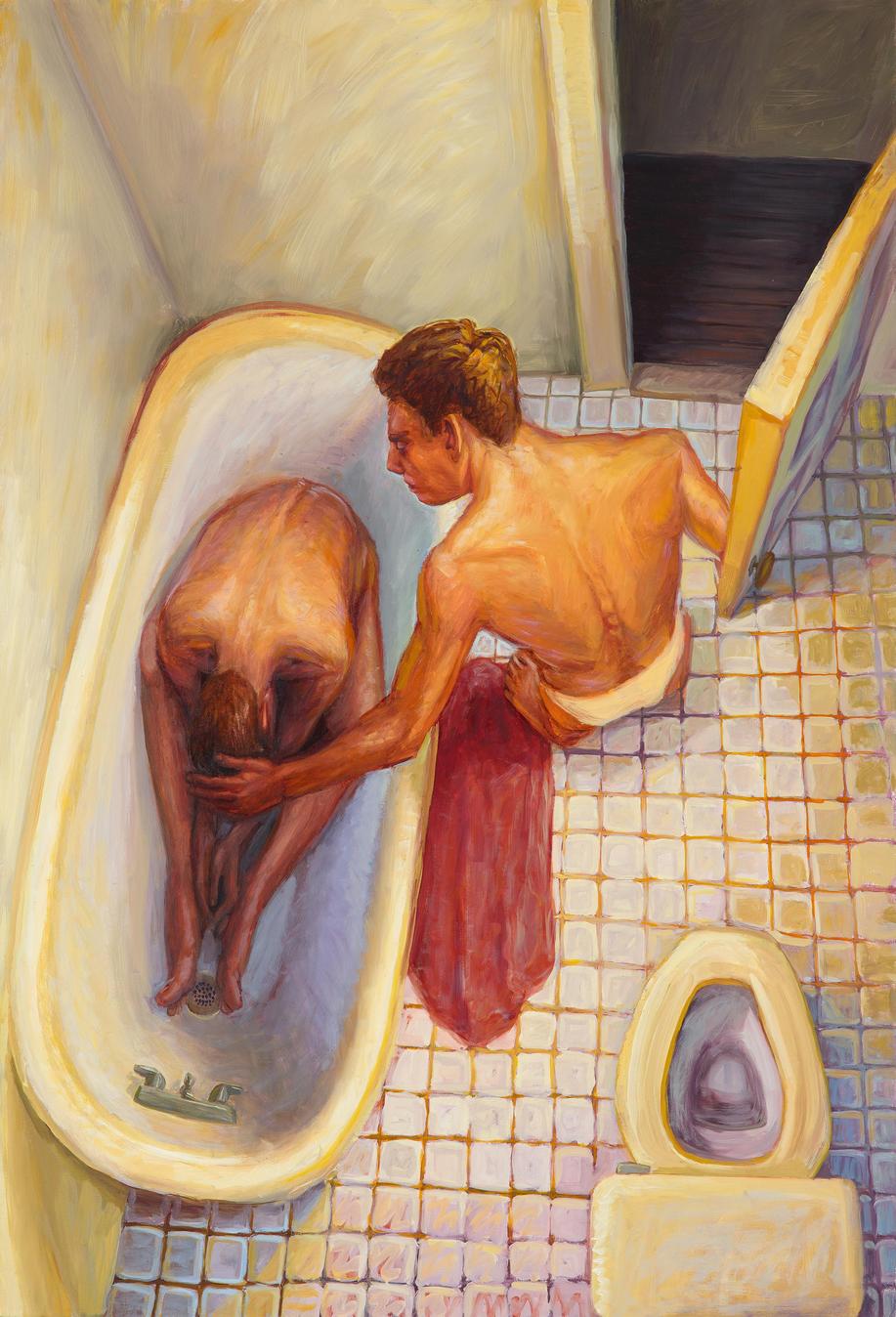

Only three years out of college, Hugh was already making a name for himself in the art world. By April 1988, he was exhibiting his work at the Drawing Center and Midtown Galleries in New York City. He had his first solo exhibition in 1989 and went on to exhibit his work in over 30 shows across the United States and Italy. Hugh came to be known for his austere allegorical works that, especially in his later pieces, reflected the queer community’s battle with AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.

Hugh died of AIDS on March 1, 1995. He was 32.

III.

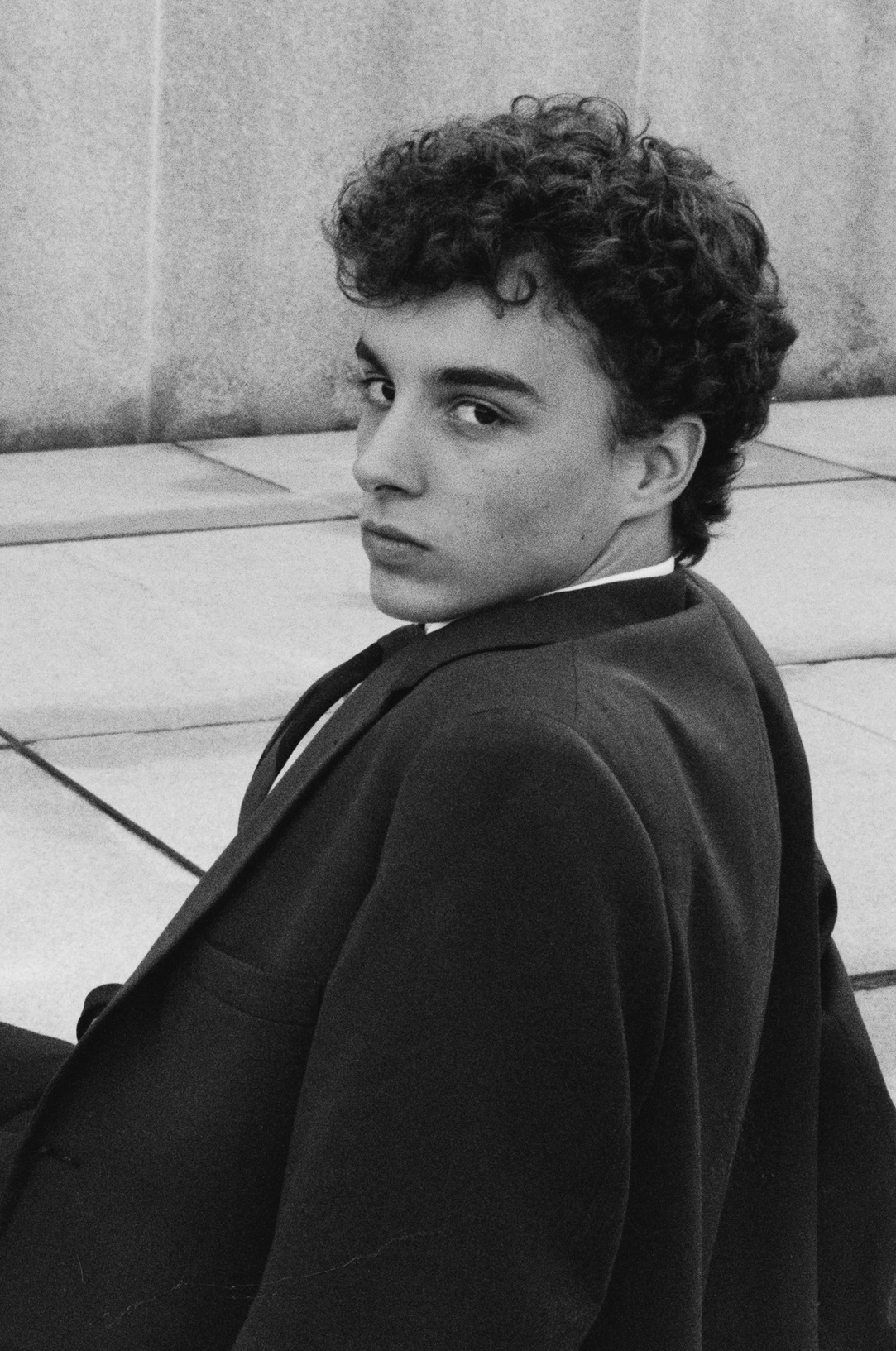

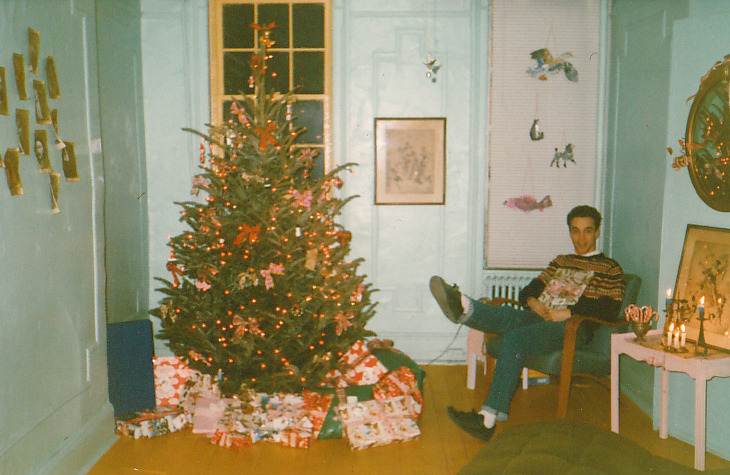

I met Hugh Steers when we were lower mids at Hotchkiss, an academically rigorous and insufferably preppy boarding school in the remote wooded hills of northwestern Connecticut. It was impossible not to be aware of his presence. His artwork, which lined the school corridors, was unlike anything I’d ever seen: anatomic studies of figures in repose; detailed sketches of hands grasping for something beyond reach. There was also Hugh’s physical presence: taller, thinner, and more stately than the typical adolescent, with an aquiline nose, curly long eyelashes, and a raucous laugh that reverberated over the dining hall din.

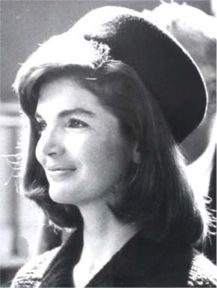

To a nerdy, sheltered kid like me, Hugh’s worldliness and verbal acumen were intimidating. It wasn’t until my second year at Hotchkiss that we became friends, drawn together by our presence in the same honors level classes and by our shared failure to fit in to the school’s social mainstream. As a clumsy, bespectacled introvert, I would have had a rough go of it in any high school, never mind a gilded place like Hotchkiss, where being of Jewish and Mediterranean Muslim extraction made one painfully peculiar. Hugh’s background was entirely different and much more in keeping with the school’s patrician façade: his father, Newt Steers, was a Hotchkiss alum and a liberal Republican congressman from suburban Maryland (a species that sadly went extinct sometime in the early 1990’s). His mother was, from my plebeian perspective, about as close to being royal as an American could get: granddaughter of a U.S. senator, step-sister of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, half-sister of Gore Vidal, with the maiden name of Auchincloss.

But Hugh would never fit into the cookie cutter scene at Hotchkiss, because he was quite obviously gay. He didn’t talk about it, but it was obvious: his love of women’s clothes; his enthusiastic dinnertime discussion of the latest Town and Country fashion spread; his excitement about landing a summer job at Henri Bendel. This was less than a decade after homosexuality had been struck from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, news of which had been slow in reaching Hotchkiss. It took courage for Hugh to be so openly unlike any of the other boys at the school.

But his openness had its limits. Only one classmate, Hugh’s best friend Karen, knew about his penchant for drag. “You alone truly knew me,” he wrote to her in the senior yearbook. “Aren’t you horrified? Appalled? Wouldn’t you really rather have a Buick?”

When Hugh mentioned his family, one couldn’t help but feel a bit sad. I remember him talking about how he and his brothers were corralled into smiling for staged photos, to make it appear that his father the politician had a happy family. One time, when I was complaining about the impending arrival of my somewhat domineering father, who was driving three hours to help me with something or other, Hugh shut off my adolescent drivel. “You know, Erin, you complain about him, but you are lucky to have someone who cares about you so much that they would take the time to do this.”

While we were friendly at Yale, we quickly moved into different circles. Most of my friends were bookish and not particularly glamorous (nerds like me—yeah!—hope I’m not offending any of you, whom I adore). Hugh, on the other hand, gravitated toward a more glittery and artsy group. Yale in the 80’s was a great place for a gorgeous gay guy like Hugh, and he seemed to thrive.

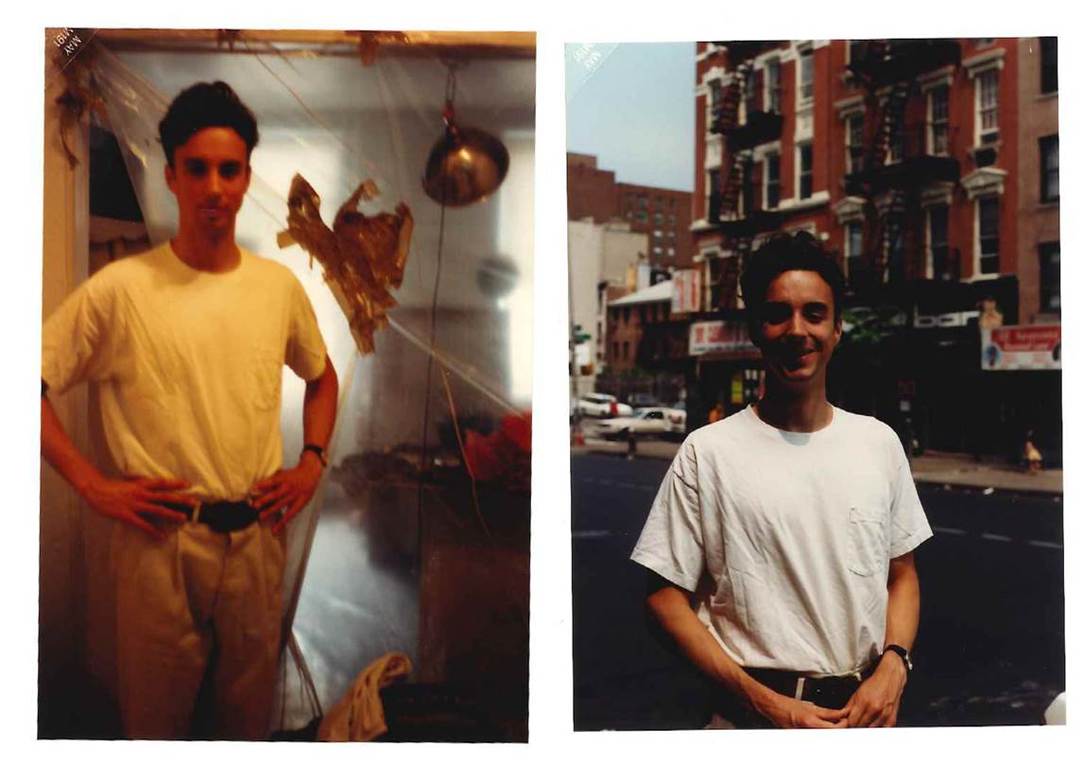

Sadly, it also turned out to be a treacherous time. I remember first hearing about AIDS as a Yale senior, when Rock Hudson became ill. I learned of Hugh’s illness a few years later, after a friend told me she had read a letter he had written to Vanity Fair blasting the Pope for statements he had made about gays. In the letter, Hugh mentioned that he had just been in the hospital for AIDS-related lymphoma. He and I met up later that year in Alphabet City, where he was living in a small apartment and working as an artist. He was the same old Hugh, sharing stories of his mom’s travails through law school, and exuding pride about the efforts of his younger brother, Burr, who had been working on behalf of women’s health clinics. But we also talked about his failing antiretroviral regimen, and the molluscum contagiosum that was creeping across his beautiful face.

Hugh died shortly before doctors started prescribing combination highly active antiretroviral therapy, a change that transformed HIV from a death sentence to a chronic disease. He had always been meticulous about his health, exercising and taking a pharmacopeia of vitamins; if he had just survived a couple more years into the combination HAART era, I suspect he’d be alive today. While his paintings are a valuable reminder of a terrible time, I can’t help but weep inside for what we lost, and wonder what he would have continued to create.

I was always late. For our coffee and dinner dates, our long walks and talks in Central Park, for visits to his studio and the many club hops that shaped our nights. I can see him sitting on a stoop or standing on a street corner expectantly looking out for me – sometimes worried, never mad – and the delight springing to his face when he spotted me. No one since has ever been quite as happy to see me as Hugh was every time we met. This memory visits me often, the image of him waiting for me.

Long before his diagnosis, Hugh took time seriously and couldn’t bear to waste any of it. I remember after our graduation ceremony while most of us were milling about dazed and confused, Hugh was packed and dressed to board the train for New York where he was to start his job at the Dia Art Foundation the next morning. No boozy farewells for him, his eyes were on the prize: to become an artist of the first order. There was also the reality of supporting himself, having little access to the storied wealth he descended from. His family came with heavy baggage, though none of it bearing any of that old money. Hugh was on his own. He saw the steps ahead of him so clearly: to perfect the painting techniques necessary to build a singular and enduring body of work, then to go out and hustle it. For Hugh this meant a monkish discipline, and even more impressive, a refusal to abandon figurative painting at a time when few were buying or even considering representational art.

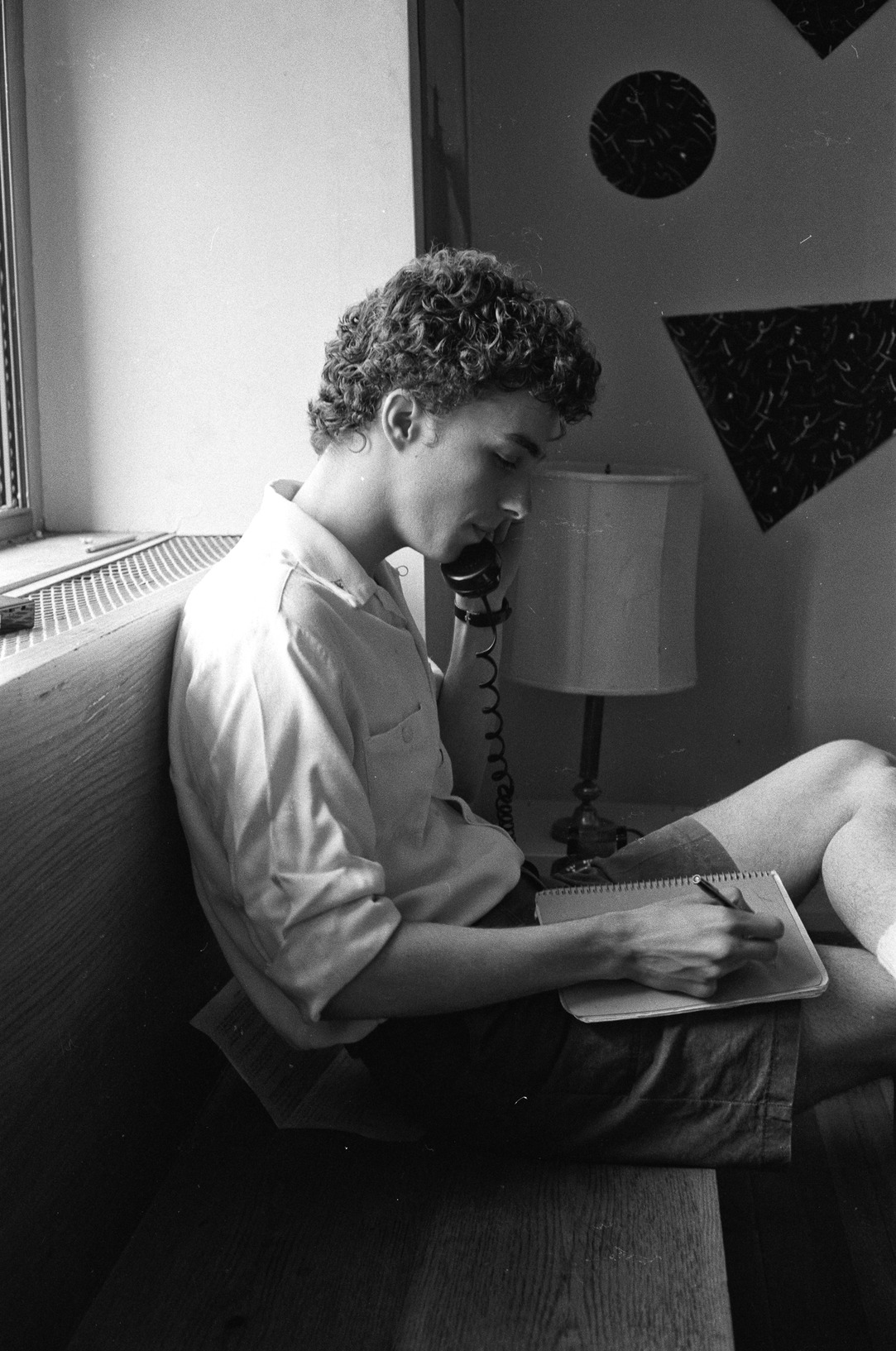

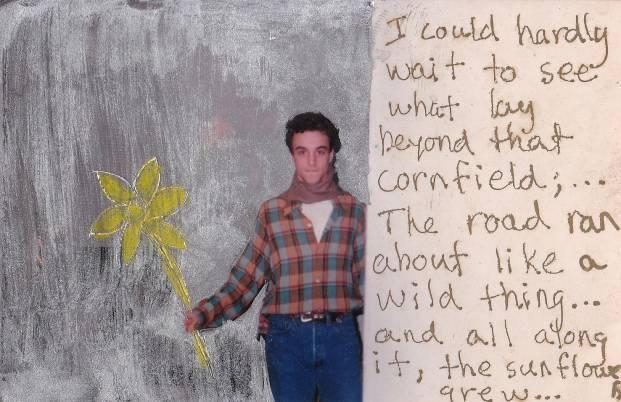

Our friendship blossomed after Yale, first in New York, then most memorably in the letters we exchanged once I moved to Los Angeles to become a filmmaker. We both knew he was HIV positive by then. Long distance calls were expensive, so we consciously dipped back into an epistolary mode, exchanging letters, music and clippings of writing and ideas that thrilled us. Mostly, we consoled each other through our hapless attempts at love. Hugh talked about what the disease was doing to him and his work. He was hesitant at first to make his illness a subject in his paintings, thinking it would make them merely topical or social commentary. Inevitably though, living with AIDS quickened the pulse of his work and acted like a crucible to distill what was most vital and precious to him.

In a letter after one of his art shows proved less than groundbreaking, he wrote: “I sort of feel like Bette Midler’s description of the Rose, ‘She gave and gave ‘til no one gave a shit.’ In the creative arts, one spends all this time in isolation working and nobody knows or cares what you’re doing.” Still, Hugh pressed on and grew ever more determined in his approach to painting.

I’ve finally come to accept my lack of facility or capacity to convincingly shift styles as a virtue… I think I value single-mindedness, a “burn all bridges” approach. To me it signifies the Artist has put everything on the line and that lends power to the work.

Hugh was right about his art. His painting evolved into a singular style that grew in intensity and focus, and near his death, took flight. In his last series of paintings, “Hospital Man,” a heroic, angelic figure, gives exquisite form to Hugh’s reckoning with death.

My Hospital Man series is coming along nicely. In fact, it’s literally taking off. I have this idea for a painting where Hospital Man is ascending off the canvas upper-right, his body visible only from the chest down, nude under his billowing hospital gown and sporting some lite [sic], airy white sling backs (not the usual mega-platforms). Lower left is a supine Adonis “expired” after sex or illness. I’m really going off, but I think my technique is there to make it work. Remember how we talked about one’s art creating one’s consciousness rather than exposing some pre-existing truth?

Pouring everything he had into his work – his humor, rage, intelligence, and most of all, his tender heart – he took his own death in hand and pulled off a sublime exit. Hugh soared.

I am rarely late now. After Hugh died, running late would often trigger the image of him waiting for me, and oh, the remorse! It took me to middle age to finally catch up to Hugh’s burning sense of time and purpose and return to a long deferred dream to write. If I’m lucky now, I have twenty years to become a writer I would want to read. It feels late in the game, but then I remember what Hugh was able to do in a handful of years. I can hear him saying, “Girl, what are you waiting for? Get to work.”

Hugh was dedicated and structured with his work schedule—every day from 10am until 5pm—and focused on creating small oil on paper paintings that depicted intimate moments between men in simple domestic settings. When he did work on large canvases, propped up on a huge wooden easel in the cramped quarters of the kitchen, the proportion and scale of the finished work gave the paintings a wonderfully warped perspective. He worked diligently on getting perspective just so—laboring over a pair of legs or outstretched arm until he’d call and excitedly exclaim that he’d finally gotten it right.

I was the first person to buy Hugh’s work. I especially loved the small oil on paper works and bought several of them or $75 each—a substantial amount for both of us. I’d pay him and then, with an insouciance that defined the time, we’d blow the money at the Pyramid Club hanging out with his friend Hyun Mi Oh, or at the Bar—a neighborhood gay hangout, drinking martinis—him vodka and me gin. The artworks thus became known as the “martini suite”.

Hugh and I bonded instantly, first as lovers, then as best friends. We met in the mid-80’s working for New York’s premiere florist and party planner. The job provided each of us with the means to pay rent and to make our art—Hugh’s, painting and drawing, and mine, film and collage. Around the same time, I asked Hugh to be in a super-8 film I was working on called “The Boy is Gone,” which was based on a poem by Edgar Oliver. Hugh was to have two parts—as a young boy abandoned outside a railroad station and as a mourner at a funeral. Looking back, both roles seem prescient: we were soon to learn what it meant to be abandoned and, disproportionately to our age, have death all around us.

One day in 1990 or 1991, Hugh told me that he had found a wonderful apartment on Avenue A—a railroad flat directly above a pizza parlor. He was a privileged white kid who had just graduated Yale who was now living in New York’s East Village with punks, radicals, artists, nightclubs, performance spaces, galleries and artist run storefronts, homeless people everywhere (Tompkins Square Park was a tent city). I’d hang out there and watch him paint, although he generally preferred to be alone when working. The windows were always wide open to the noise of the street and the smells of hot pizza wafting throughout the apartment—he didn’t mind, he was in heaven.

It wasn’t until two of our closest friends had died from AIDS that Hugh told me he was infected. He was determined to forge ahead and to take whatever treatments were available to combat the disease. There weren’t many in 1993. He responded to the illness through his art, depicting images of bravery and tenderness, humor and rage while boldly critiquing the government’s inaction, endemic homophobia, hateful religious fundamentalism and opportunistic corporate greed in the midst of a spiraling epidemic: a lot to manage for a 30-year-old guy, especially as his own health rapidly deteriorated. But Hugh persisted and continued to paint every day in a basement studio in Tribeca; it was during this time that Hugh’s health really faltered and began its descent. When Hugh died March 1, 1995, his brother Burr, Hyun Mi and I surrounded his bedside, held his hands and spoke softly to him, encouraging him to let go and assuring him that we would be okay. After having fought so hard for so long, he slipped away with one long, last breath releasing his gentle soul into the world.

As a man of 54 years—many of which I’ve lived with AIDS—it’s hard to comprehend the cruel chaos that defines who lives or dies. But, through his artwork and life, Hugh humanized AIDS and the awful and sometimes strangely hopeful ramifications of the disease. Hugh raised the bar of culpability and pointed an accusing finger at those whose willful inaction or callous reaction condemned so many to die, while making the void, the absence, the injustice, the stolen potential of this holocaust heart-wrenchingly clear.