I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

Frank Moore was a painter, naturalist, and founding member of Visual AIDS, one of the most important groups of AIDS activists in the art world. An award-winning artist, Frank also helped launch the Red Ribbon Project, which gave the disease its most recognized image. Frank approached his work as a scientist courting revelation. “The guy who figured out the benzene chain was daydreaming in front of a fire and saw a snake grabbing its tail and realized benzene was a ring,” he once said. “That happens in art, too.” His work is represented in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the New York Public Library.

Born in Manhattan in 1953, Frank grew up on Long Island and spent summers on a family farm in the Adirondacks. A lover of nature, he was an early and eager collector, accumulating butterflies, orchids, moths, shells, frogs, and bird eggs.

In 1970, Frank went to the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle, Maine to study painting. The following year, he matriculated at Yale College. He graduated in 1975, Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude, with dual degrees in Art and Psychology.

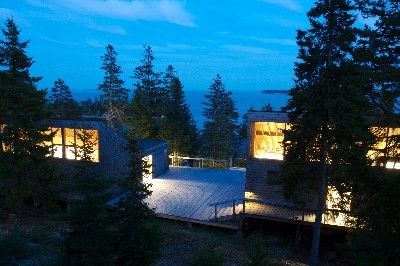

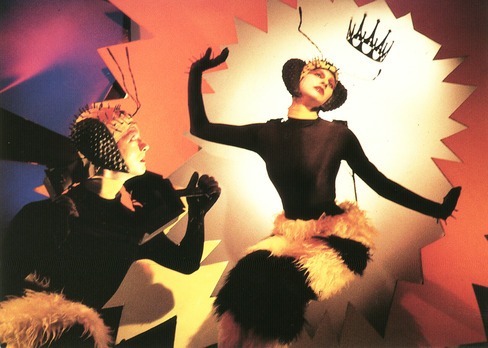

In 1977, Frank moved to New York City, where he began a career as an artist and designer. Between 1977 and 1979, he studied at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, supporting himself by teaching English to Muslim youth. In addition to creating paintings and drawings, he designed sets and costumes, most notably for the choreographer Jim Self, with whom he created Beehive, a ballet film short, which won a Bessie in 1985.

That same year, Frank learned he was HIV-positive. From that point on, AIDS became a central theme in his work, often appearing commingled with his other main interests: the environment, homosexuality, and the health care system. Although Frank viewed his work as political, its animating spirit was curiosity rather than anger or alarm. “The AIDS virus is just a virus,” he once told an interviewer. “It has no personal agenda against me. It’s just another creature in God’s creation.”

Frank lived through several phases of the AIDS crisis, repeatedly fending off death with the help of friends and family. After nearly winning a seventeen-year battle, he finally succumbed in 2002 at the age of 48.

II.

III.

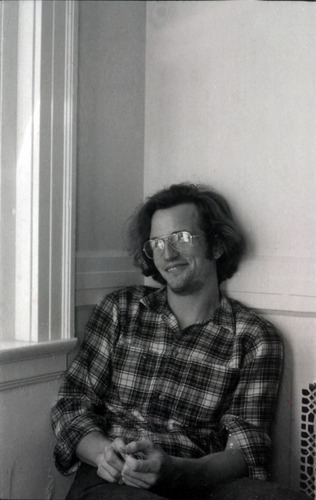

I met Frank as a favor. In the early fall of 1971, the beginning of my sophomore year, my friend Richard Kramer ‘74 asked me if I would be willing to go meet a freshman, the son of one of his mother’s best friends. He had been assigned to the same college as us, Silliman, so there was no way Richard could avoid him. “I’m sure he’s a nerd,” Richard said. “Just come with me, we’ll be nice to him once, and then we’ll never have to deal with him again.” I couldn’t have known that day that my life and Frank’s would be intertwined for more than twenty-five years.

Frank was a phenomenon, and there was hardly a man, woman or child, teacher or student, who didn’t to some degree fall in love with him. And he was annoyingly smart—he easily achieved honors in all his classes while never seeming to sweat anything. Even though it was clear he was an artist to his fingertips, I remember him telling me that the Russian department was pressuring him to major in Russian Studies, because, yes, he was brilliant at that as well. (No one seemed to care what I majored in.)

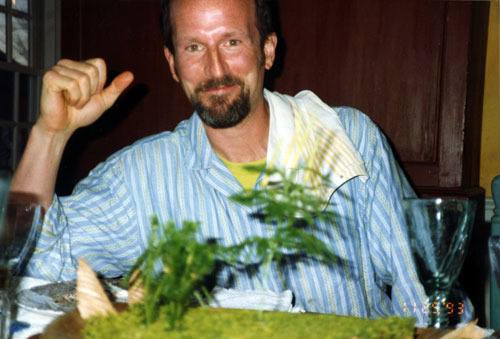

And I have never met anyone as fully engaged in, and delighted with, the physical world. He knew the Latin names of seemingly every plant and tree. His love of food nearly matched his passion for art. He introduced me not only to Ellsworth Kelly but also to Marcella Hazan, and he knew every obscure but delicious restaurant in Chinatown.

He loved old movies, episodes of I Love Lucy, and collaborating with dancers and choreographers. He could be as self-involved and oblivious as any artist (he set me up on the single worst blind date I experienced during my long and checkered dating career.) But his charm always won out. Frank, it seemed, could get away with anything.

Even as his life became increasingly complicated, when he was managing his own HIV diagnosis, taking care of his beloved friend Robert Fulps, running two households and two studios, and planning and executing his detailed, dense, and magical paintings, he never lost sight of simple pleasures. Once, in the kitchen of his house in Deposit, New York, I asked him for a glass of water. As he handed it to me, he said, “Don’t you love how the water here is always so cold, because the well is so deep? That just doesn’t happen in the city.” That was so Frank, in the midst of everything, to take the time to notice—and marvel at—a glass of water.

On 9/11, I was with my girlfriend, Carrie, at our place in the East Village, and Frank was at his loft on 14th Street. We spoke early that morning, to be sure all was OK, and Frank volunteered to make calls to my mother and some other friends because our phone service was now out. We made a plan to meet up the next evening at our friend’s opening—it was a strange time to be at an opening. Though a good way to make sure friends were OK. Later that night we went to another friend Nancy’s birthday party in the East Village. She told us that earlier that day she and a few other friends had gone down to Ground Zero to take a look around. And that was when Frank, Carrie and I decided we needed to go down too and take a look for ourselves. By this time watching all the constant coverage on TV was overwhelming, frightening and numbing. Early the next morning, Frank, Carrie, myself, and another friend, David, rode our bikes down the East Side and parked them under the FDR overpass at Water Street. As everyone says, it looked like a nuclear holocaust. What was amazing, though, is that in those first days it wasn’t cordoned off. Really, anybody could walk in.

Everyone and everything was silent as we worked our way down to Church and Rector. We could see what was left of the metal filigree of the front of the World Trade Center—rising before us and hanging like strange leaves. Frank was very tall—like 6’2’’—and he had a camera, as we all did, and the four of us walked one in front of the other, none of us spoke, just following Frank. As Frank walked a little ahead, I was behind him trying to load another roll of film into my camera, when all of a sudden this cop stepped out in front of me and said, “Where do you think you’re going, young lady?” The cop wouldn’t let the three of us go any farther. Frank, of course, kept walking. He was wearing jeans, and a messenger bag, and he walked with a great swagger—they must have thought he was one of the workers. We waited, thinking he would just come right back out, but of course he didn’t.

About twenty minutes passed, and the workers around us with walkie-talkies started saying “The Millennium Building is coming down! RUN!” And everyone starts running towards us, so the three of us turn around and hightail it out of there with them.

Another half-hour goes by. No Frank. I was frantic, and kept thinking to myself, is this how it’s going to end? After seventeen years fighting HIV and everything he’s been through? It was crazy. Sirens were blaring, people were yelling—scary—chaos. After at least another forty minutes—out walks Frank, sauntering over, with this huge smile on his face. I was so mad at him and at the same time completely delighted to see him again.

Frank had gotten all the way in, and photographed the chain of buckets that were removing the overwhelming debris. We asked what had happened and he said, “Well I was standing to the side taking photographs and then everyone starts yelling and running, and I got pushed into this little deli with about twenty-five firemen”—and of course you know he loved that—“I kept taking pictures, and then this guy came over and said, ‘Excuse me, who are you?’ And I said ‘I’m Frank Moore,’ and he said ‘well, Mr. Moore, we’re going to escort you out now.’” That’s what he was like—taking every moment in and making the most it, always curious and always charming. Life was an adventure. The photos still exist—they look like the landscapes in his paintings.

Of course, we should have worn masks that day, but we didn’t. It was ironic, because that night I helped Frank pack up his things to go upstate to Deposit, both of us thinking the air would be better for him up there than it was here. Sure enough, by Thanksgiving, the doctors said that Frank had contracted non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. I still wonder—with his immune system being so compromised—whether wandering around the ruins of the World Trade Center is what finally put him over the edge. It was just like Frank though—another give and take with his environment, his world—taking in the magnitude of it all and replying.

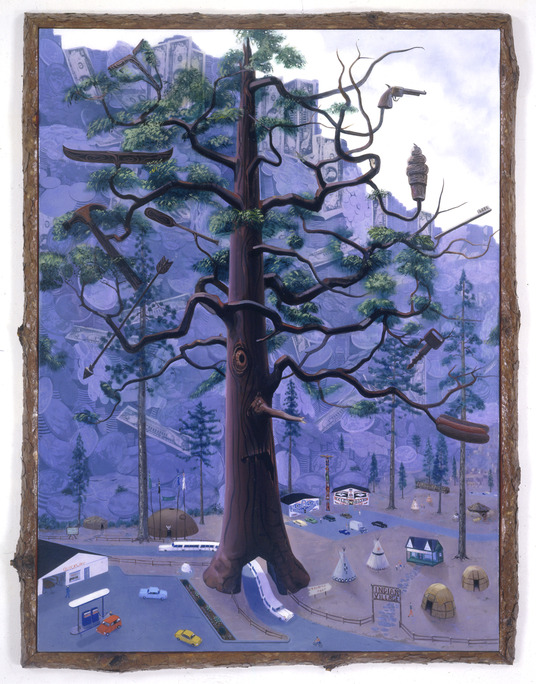

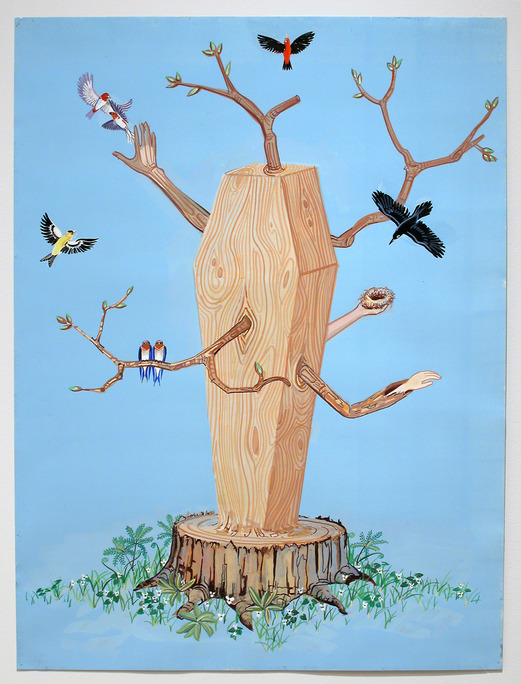

In painting, Frank drew connections, sketching a humanist vision of how the world was, and what it could be, even as he pointed to that which is hardest to look at—greed, environmental degradation, homophobia, the voracious maw of industry, death. Even there, in the detritus of an abandoned lot, in the cold expanse of a hospital bed or the scorched earth of experimental drug trial, he could find something beautiful—a hint of redemption even within our biggest missteps.

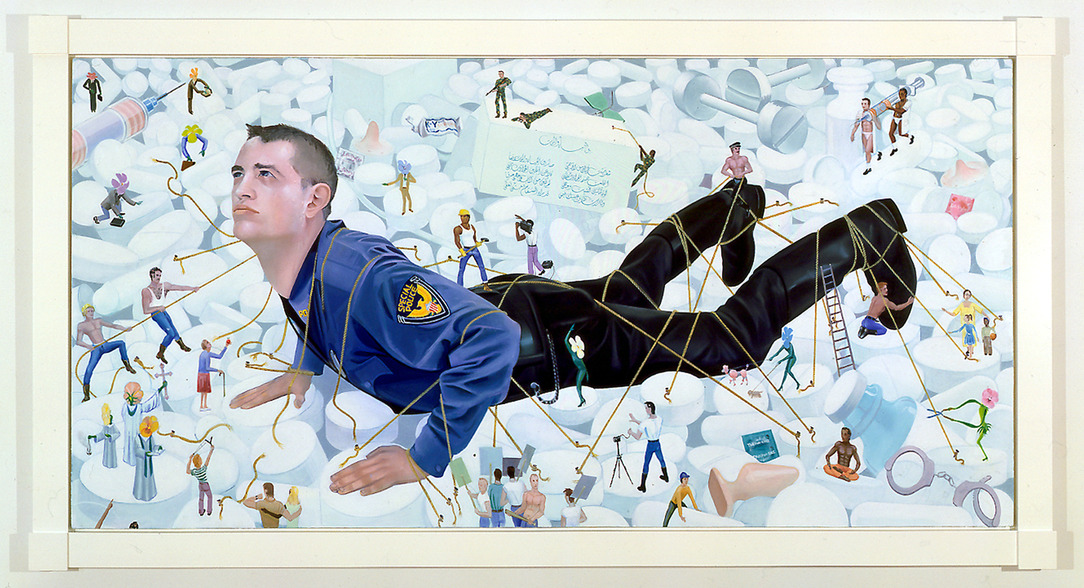

At the same time, Frank could paint real things as if they existed in a fairy tale. In one painting (which I’m fortunate to see every day, on my wall) a village of cartoon figures urges a gay Gulliver to break free of his bonds. (Or are they tying him down?).

Frank’s work was not political in the sense of trying to accomplish specific ideological objectives. But in examining connected ecosystems—the global effects of genetic engineering, the love affair between oil interests and agriculture, or multiple impacts of a virus, bodily and cultural—his paintings often led to political insights. And in rendering the hollyhocks that towered outside his Catskill farmhouse windows, the thunderous falls of Niagara, or the glass of water with which he washed down his daily doses of medication, he quietly embedded meaning.

Frank had an old soul and the alert playfulness of a child, and time spent with him was both simple and complex. Once while driving up to the Adirondacks, to summer camps where each of us had grown up, we stopped at the grave of Baron von Steuben. Von Steuben, a Prussian military officer considered the most important general in the American Revolution after Washington, professionalized the first US army. He was also unusually close to his translator-aide, the original “gay in the military.” The day following our pilgrimage, Lady Diana died, and on the next, we found a moose track left on the dirt road leading to my family’s house. It was the first moose to wander in the region for decades; Frank insisted that we cast it in plaster.

That much might happen when with Frank. After miraculously surviving what seemed like more than nine lives, he is gone. I carry Frank with me, the promise of his bodhisattva nature. He urges me on, with wisdom and patience, to expand my world, to hold all the contradictions he saw and make something better of them.

I met Frank Moore in the early nineties because everyone said I had to. I had started the Estate Project for Artists with AIDS and Frank’s name came up again and again as someone who was at the center of the work being done in the New York art world to address the AIDS crisis. Frank would come to be enormously important to me as a sounding board and also something of a negotiator between the Estate Project and Visual AIDS, which were the two primary organizations dealing with artists living with, and lost to, HIV.

More importantly, Frank became my friend. He and I told one another that we had “mega-intimacy.” After a disastrous few years in New York, having lost my lover to AIDS, I moved to Los Angeles. But when I was in New York, I would see Frank and we would instantly pick up where we left off.

My memories of Frank are mostly of spending time in his loft on Crosby Street where, inevitably, he would be painting when I arrived. He never seemed bothered to be interrupted but he also never seemed to have spent much time thinking about my arrival. He never showed me the work in his studio. He would just walk out of the area where he was painting and we would never discuss it. It was as if we had more important things to do.

Two memories of Frank. No…three. First, of walking in a snowstorm to an Italian restaurant in Little Italy. I remember holding his hand in the most natural and unselfconscious way. Secondly, visiting his house upstate. I was dating someone else but I remember thinking that, in another life, it was Frank who would have been my partner. Finally, I remember that Frank took me to Gianni Versace’s memorial at The Met. It was in the vast atrium that houses the Temple of Dendur and it still seems so unreal to me that sometimes I question it actually happening.

One more memory. I remember the last time I saw Frank. He asked me to meet him in a hospital where he was having yet another ghastly treatment. When I arrived he was just finishing the treatment and looked absolutely white, emaciated. Yet the thing that he wanted to do was to go to a Chinese restaurant off of Times Square. He ate like it was his last meal and cherished every mouthful.