I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

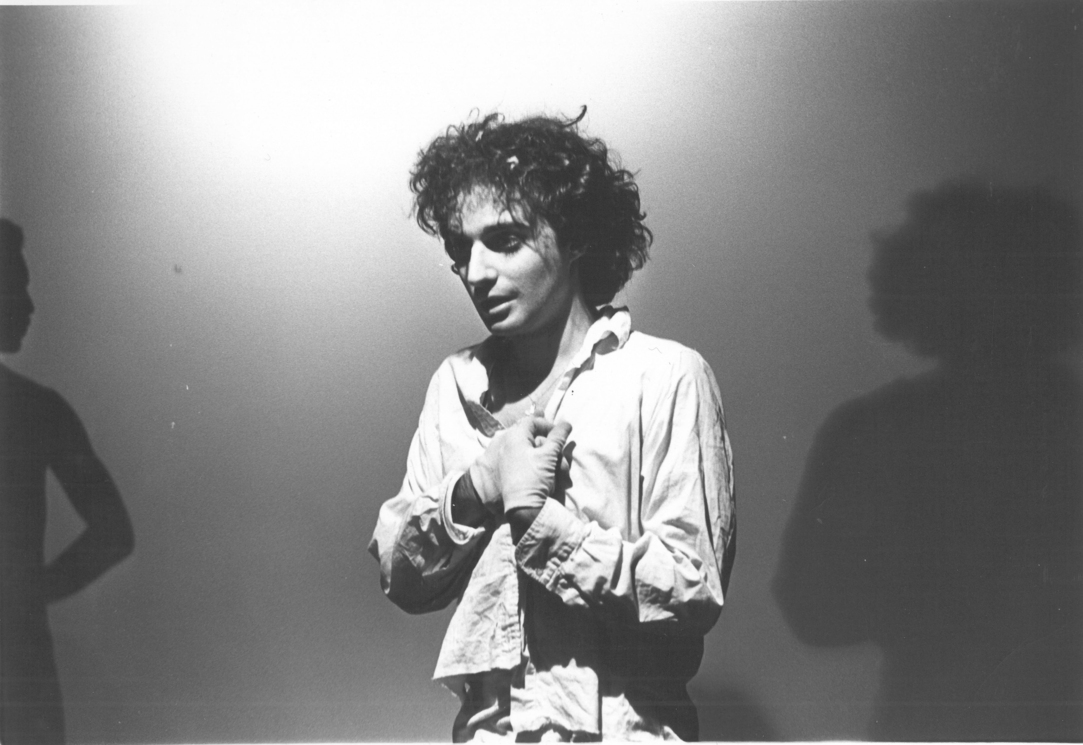

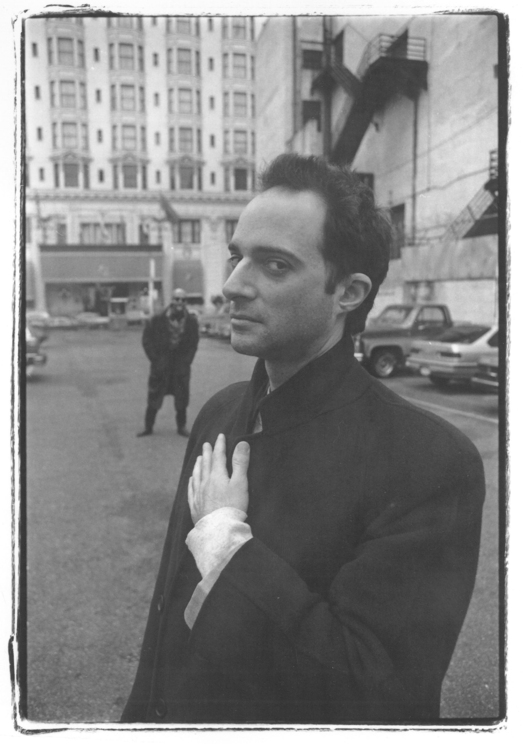

Harry Kondoleon was a playwright, novelist, painter and poet whose art dramatized and satirized the frictions and fissure of relationships between friends, lovers and acquaintances. Of his plays, his fellow playwright and former teacher John Guare said, “They may be brutal, but they’re written with such high-style elegance.”

Harry Kondoleon was born to Athena and Sophocles Kondoleon in Queens, NY in 1955. He shares a birthday with his sister Christine. He attended New York City public schools and was artistic from a young age. He was a star of the literary scene at his public high school in Queens. He graduated from Hamilton College in 1977.

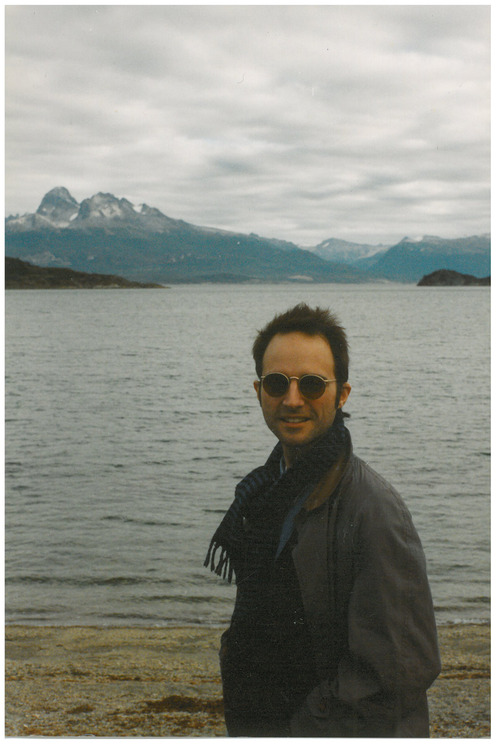

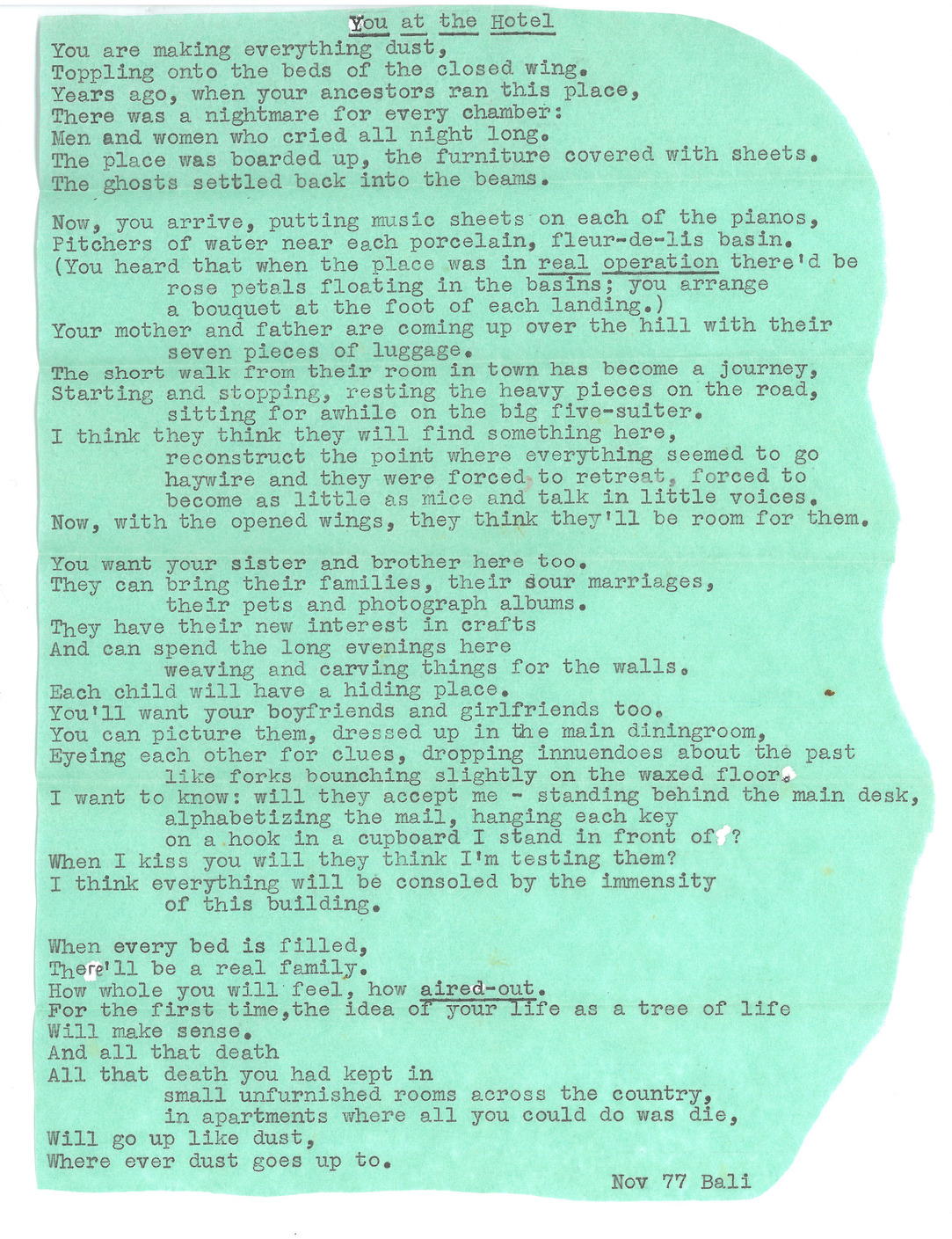

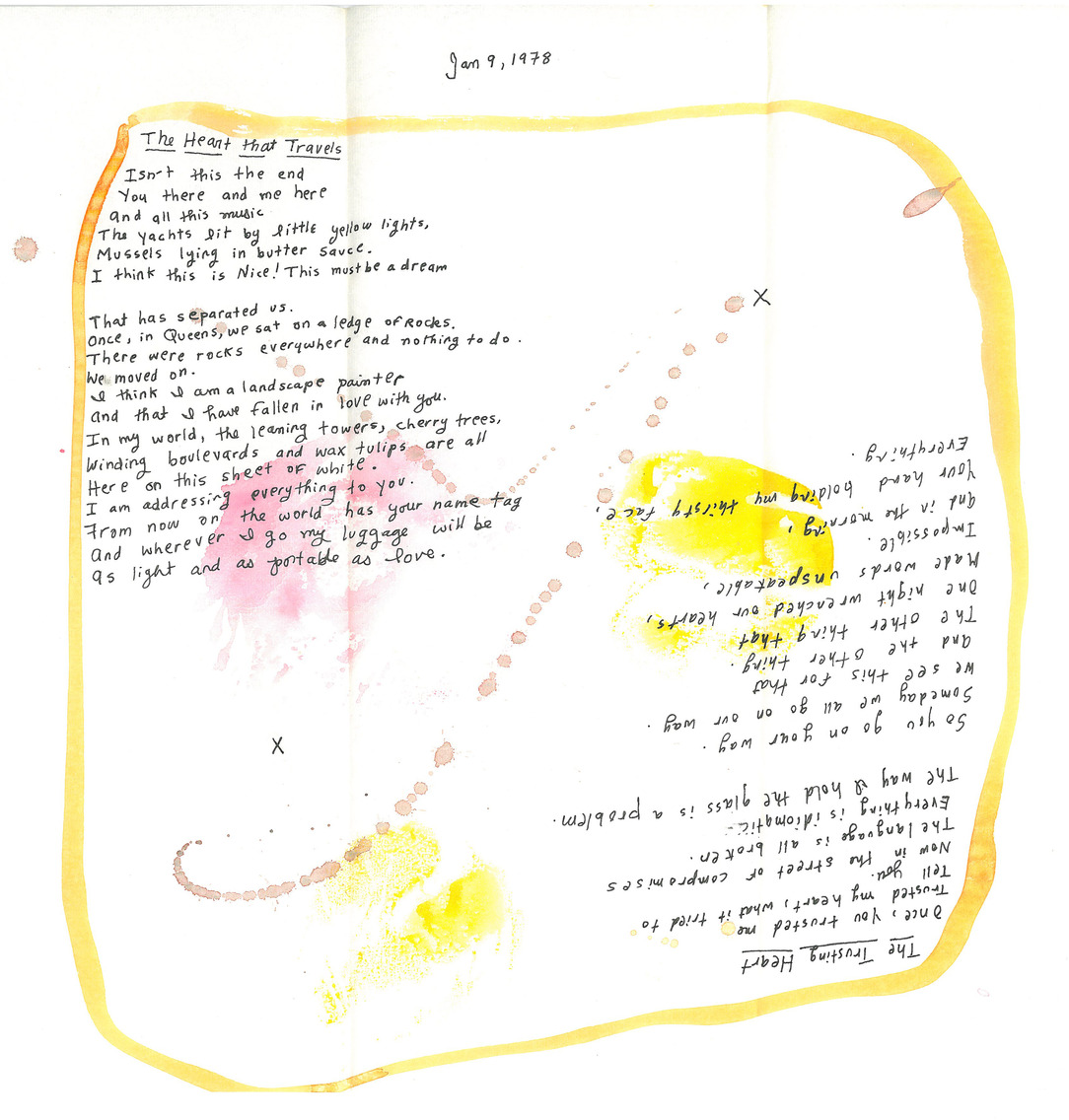

After college, Harry received a fellowship from the International Institute of Education to travel to Bali to study Balinese theater. He observed theater performances, wrote a novel and corresponded prolifically with his friends. When he became ill with typhoid, he was airlifted to Singapore for medical treatment. The following summer, he spent time on the Cote d’ Azur, France.

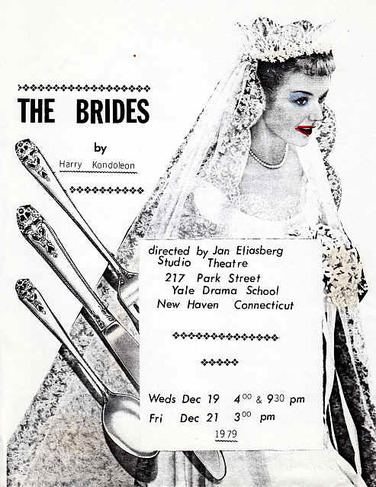

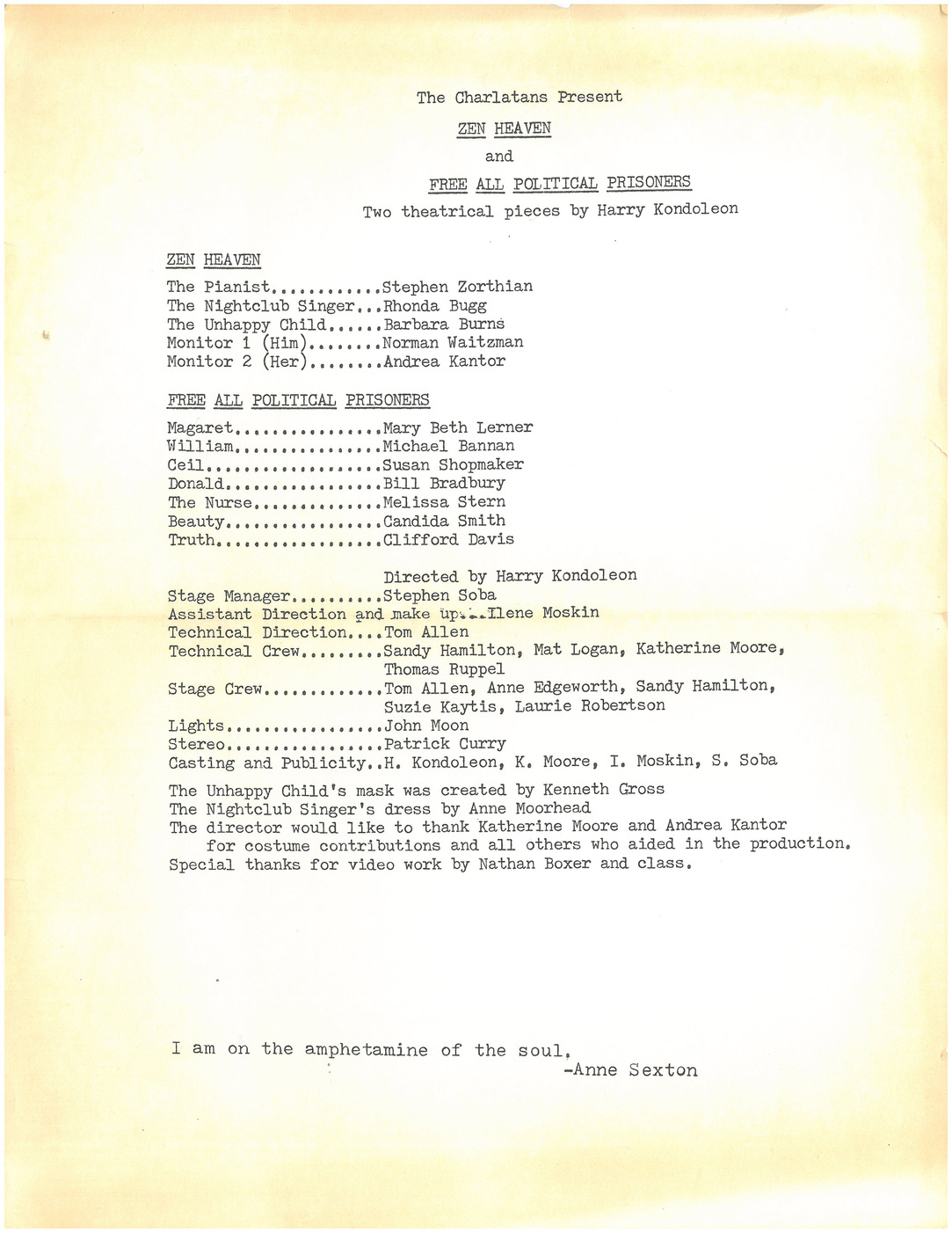

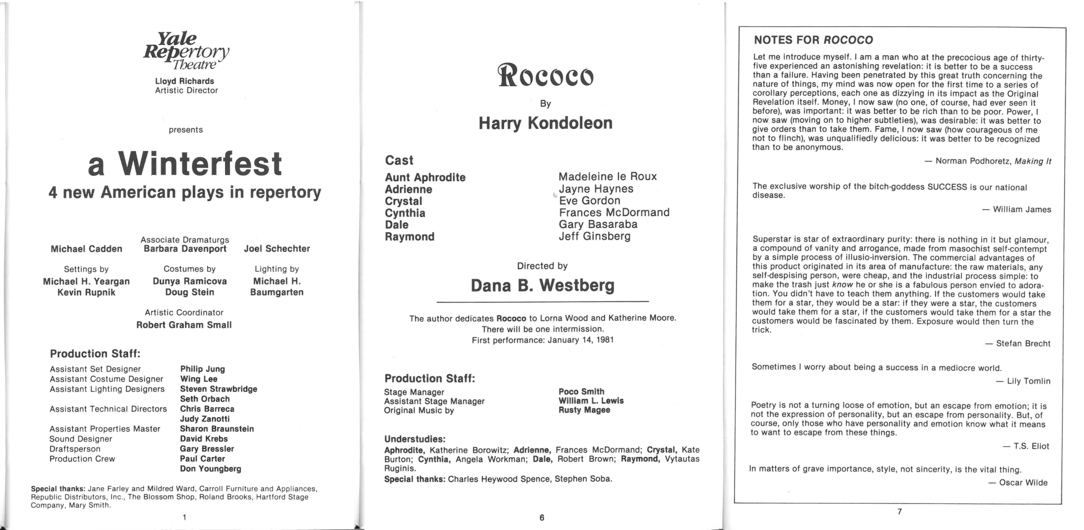

In the fall of 1979, Harry entered Yale School of Drama where he was close friends with the actor and director Mitchell Lichtenstein and actress Eve Gordon, who both acted in several of his plays. He studied alongside fellow playwright David Henry Hwang under the tutelage of John Guare. Harry graduated from Yale with a Masters of Fine Arts in 1981.

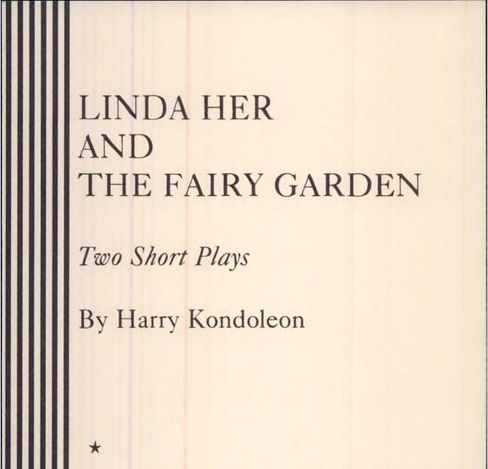

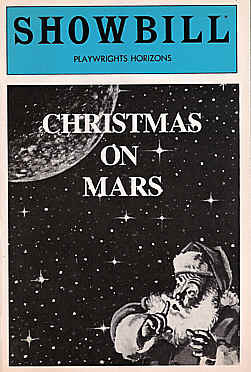

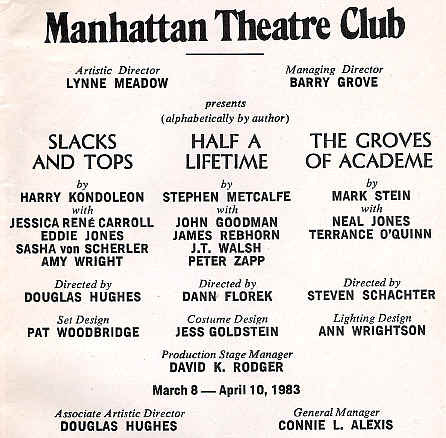

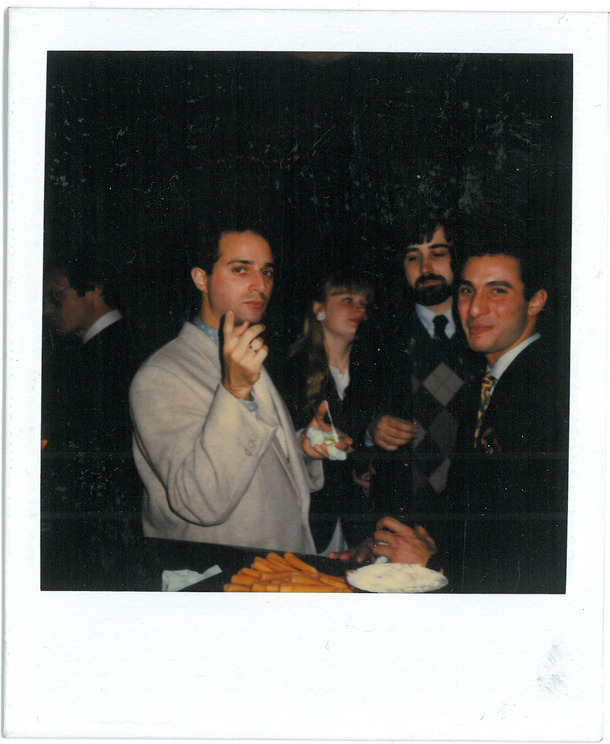

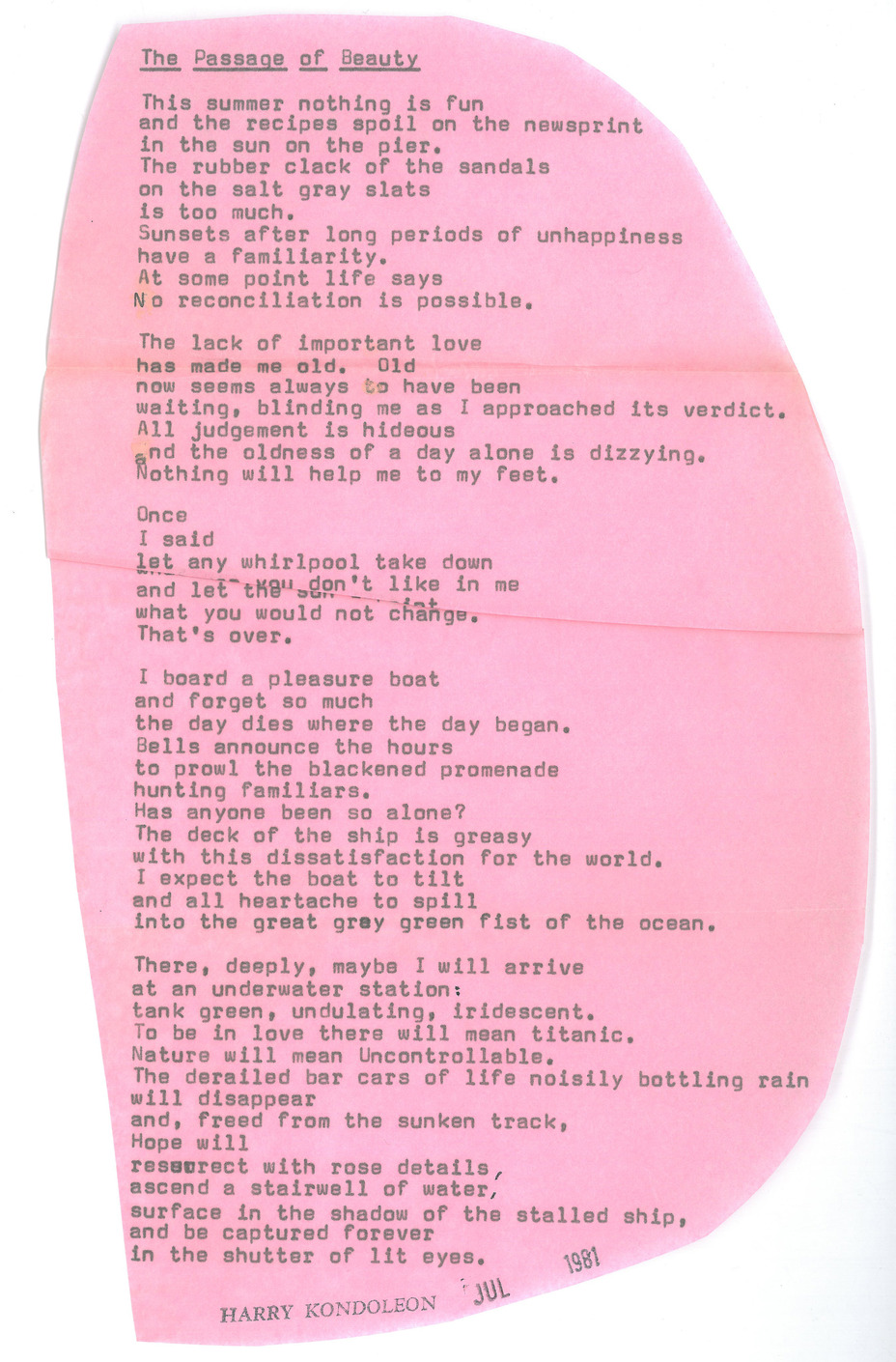

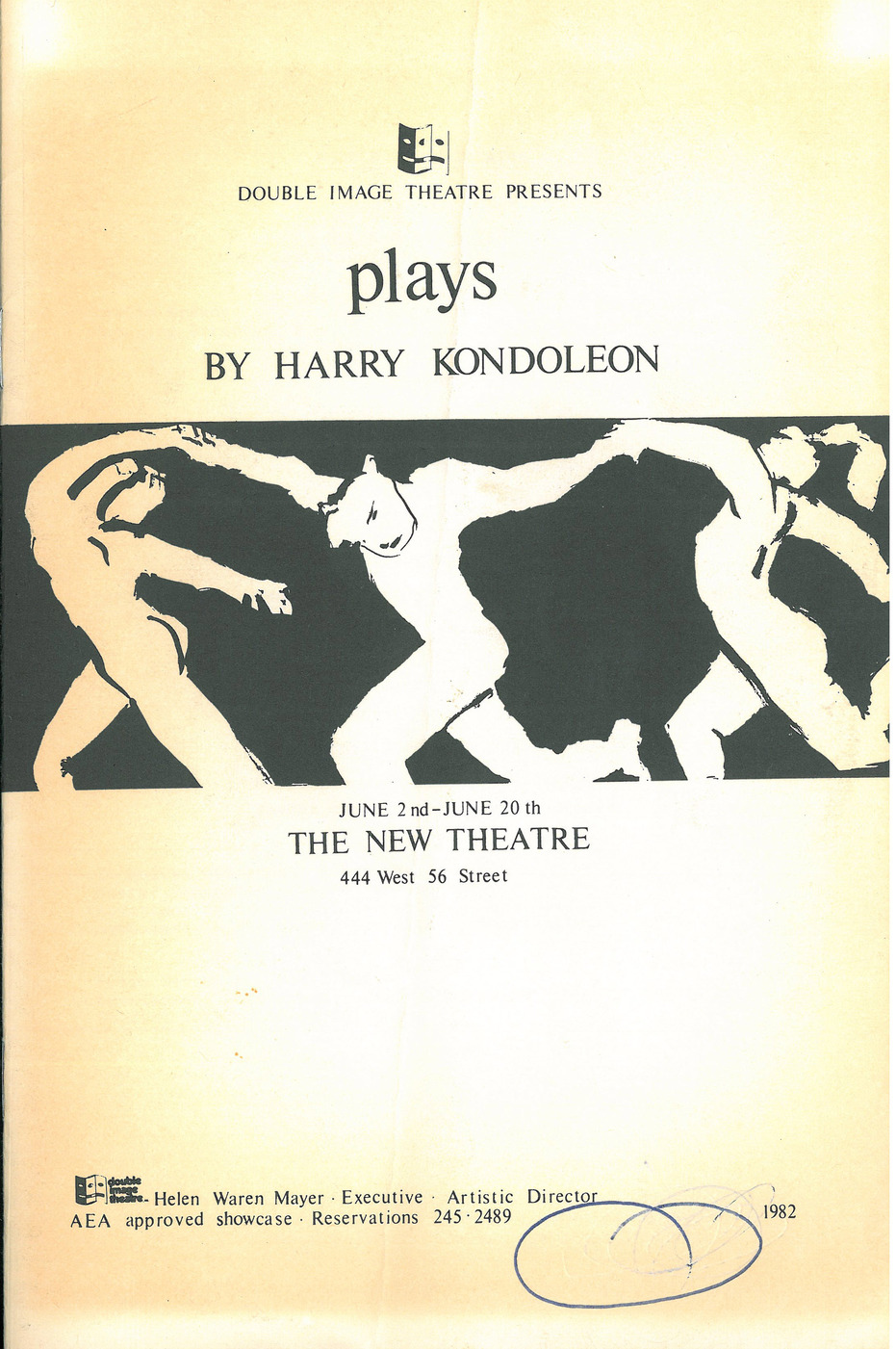

In the early 1980s, Harry returned to New York. He lived in an East Village apartment on East 10th between 1st and A. Harry showed his paintings at the Gracie Mansion Gallery. The Manhattan Theater Club, Playwrights Horizons and the Public Theater all produced his plays. The gallery scene in New York was exploding, and Harry thrived artistically alongside of Keith Haring and David Mamet, with whom he shared an Obie Award for Best Emerging Playwright in 1983. He became a known figure in the theater world.

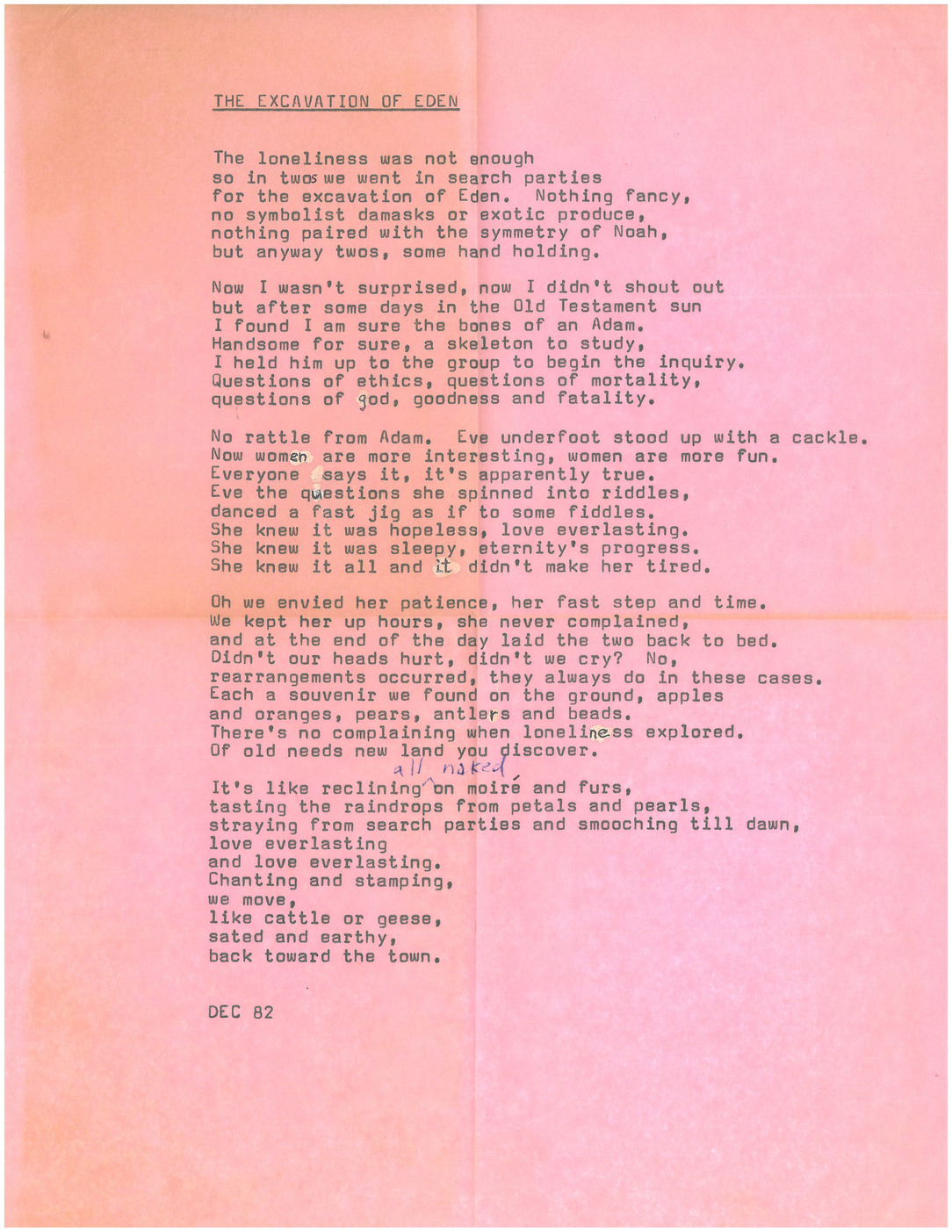

In all, Harry published 18 plays, two novels and two books of poetry. Critics received his plays with a great deal of enthusiasm as well as some ambivalence. In 1986, he was diagnosed with HIV. Soon thereafter he wrote a play called Zero Positive that was produced at the Public Theater by Joseph Papp. The last work published during his lifetime was Diary of a Lost Boy. He told the New York Times Theater critic Frank Rich that he had found the strength to finish the novel “as a personal achievement to show I wasn’t dead.”

Harry died on March 16, 1994 at the age of 39.

III.

Harry entered my room one autumn night during his freshman year at Hamilton College; I was a sophomore. Without any attempt to explain or ingratiate, he inspected the premises, on a schedule and a mission all his own. (It turned out he was investigating future housing options, but I didn’t know that yet.) My presence barely registered with him. Part visitation, part invasion, part shopping expedition: that turned out to be Harry.

Dressed like no one else, dark hair waving to his shoulders, his eyebrows half raised, he peered at my room with a grave and steady gaze, clearly unimpressed. He ran his delicate fingers over a page of the Norton Anthology of Poetry, open on my desk to the poems of Sylvia Plath.

“Sylvia,” he remarked, on a first-name basis with the writer and with a flicker of interest in me at last, “is my favorite poet in the English language.”

“Well,” I said, not yet ready to abandon Keats and Yeats, “she’s not mine,” at which he turned and vanished.

We didn’t speak again for a year and a half.

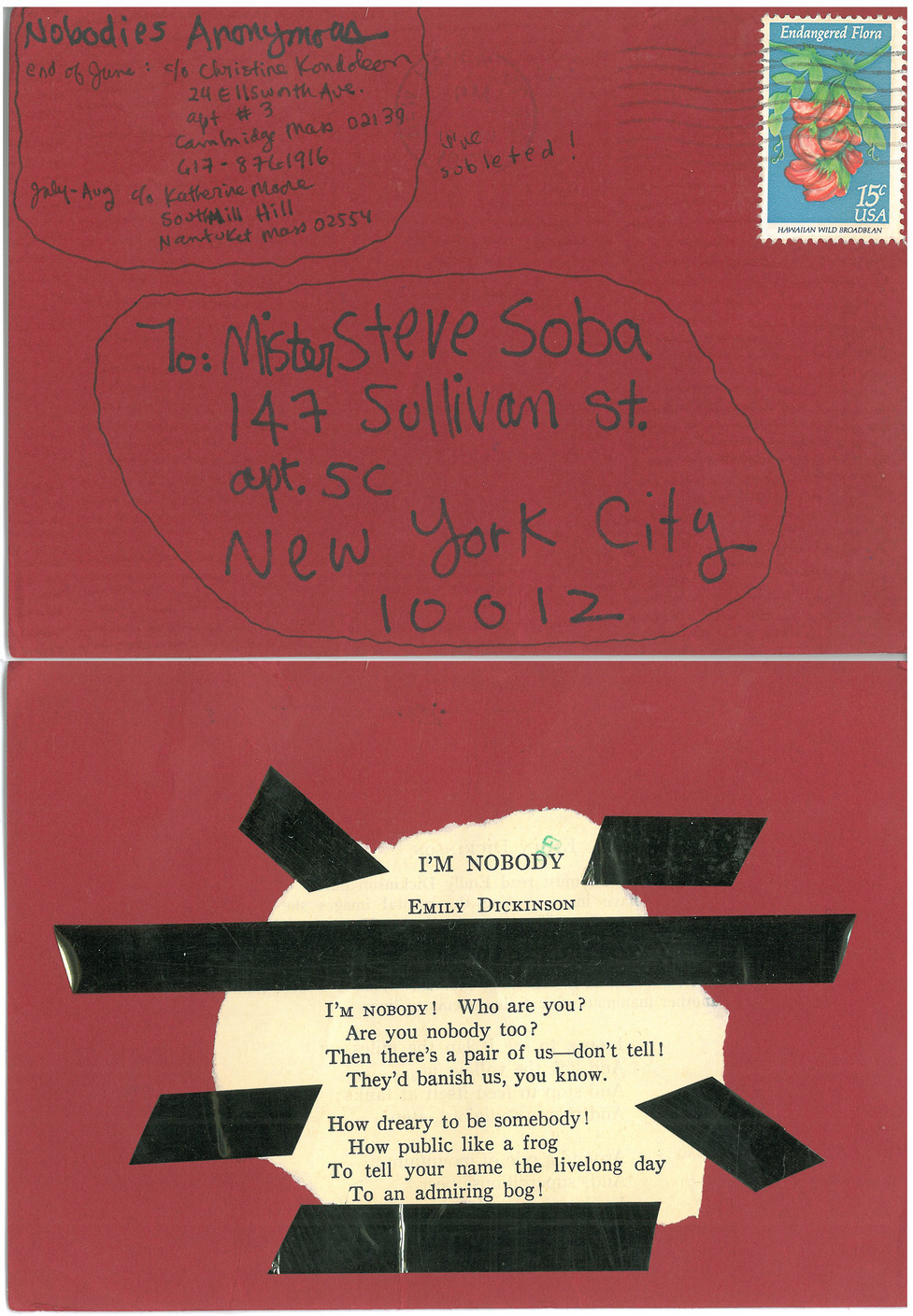

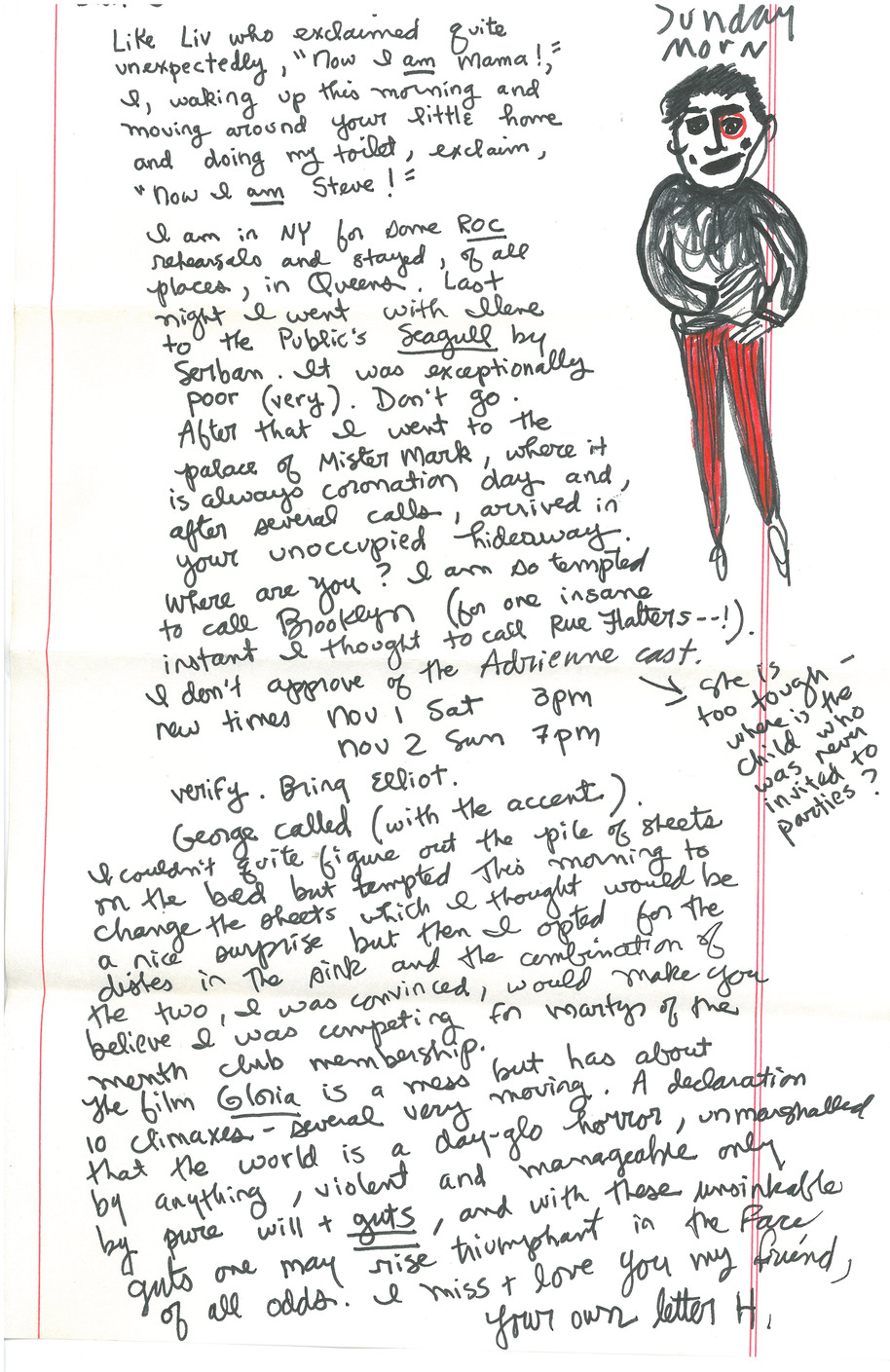

Then everything changed. I stage-managed a play he’d written and watched him direct. His writing was wildly funny, borderline mad, dangerous, poetic—fearless. I began working on all his plays. We auditioned the actors. We silkscreened posters and t-shirts through the night; I was elated when he said my shirt came out the best. His company was riveting, charged with mischief, hilarity, provocation. He gave a Dada-themed dinner party in a college conference room. He called at all hours and left notes on my door that thrilled me.

At RISD, where we spent the summer together, I slept with someone he liked and rose, visibly, in his estimation. (I’d also been assigned a better room.) Everywhere we went, he quoted from Plath and from Polanski’s films, enacting whole scenes from Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby. He incited his followers. Let down by life in the short run, he projected an air of expectation. Wherever he was going, Warhol would certainly be there.

We became the greatest friends for the next twenty years. He sent me his first novel, in chunks, from Bali, where he travelled on a grant to study Balinese theater after reading Antonin Artaud. His letters were desperate: there were dead ants floating in his tea. When he returned to the U.S., after disappointments in most of the major capitals of Europe and the south of France, he enrolled in Yale’s School of Drama. As you can imagine, New Haven did not elicit his warmest praise. From Yale, he moved to the East Village, across the street from the Russian Baths and the Fun Gallery. It was 1981, the first year of the epidemic.

He was fixated by Italian leather, autumn leaves, and art. His dream was to have you over for tea and homemade strawberry shortcake, to show you his new sandals, his new collage. At the table he’d move the flowers closer to his place, covetous of their fragrance—he couldn’t help himself. Wearing his ring with three interlocking gold bands, his fingers vibrated like tendrils of seaweed. He craved love, beauty, attention, consolation. He searched for God and for romance. He took everything in, observing the world through violet-tinted sunglasses. He reported on the classes he taught at Princeton and NYU, aghast that his students didn’t know who Blanche DuBois was. His best days were filled with painting and writing, his own cooking, long chats on the phone with friends. At Yaddo, I was told, everyone sought his company at dinner. He never for an instant feared boring anyone.

Since his death, on March 16, 1994, I have been trying to understand how he did what he did in his final years. He found the will, the courage, and whatever else it took to go on creating—plays, collages, poems, another novel. He painted a paper lampshade for me with a swirl of mysteriously smiling ghosts. He complained nonstop. He left the hospital to attend his book party, wearing a red velvet jacket. In his last days, he grew quieter. Together in the pale green bedroom of his apartment, we watched the film Charade on television, a few nights before he died. There’s a funeral scene where the character played by George Kennedy plunges a pin into the corpse to make sure it’s really dead. I don’t think either of us flinched or uttered a sound. Earlier, Harry might have joked, “Please don’t try that at my funeral,” and we’d have had a little laugh. But it was too late: the time for that had passed.

Harry and I were born on the same day—he was my second birthday present. We forged a very close bond and nurtured each other’s intellectual and artistic growth. We both felt the restrictions of middle class Queens and public education, but also benefited from the proximity of Manhattan and forays into its museums and plays. Harry was a sponge for any reading I brought home; I recall his picking up a copy of Albee’s Tiny Alice that I had for a junior high school assignment; he was just in 6th grade at that time. I believe he began to write theatrical scenes just after his discovery of Albee—Harry would come to my room excitedly to try out what he had just written. I was the privileged first reader and solo audience for this extraordinary talent.

Our mother Athena recalls him drawing from earliest childhood fanciful dresses; at about the age of 5 he started a series of paper doll drawings with colored pencils and paper. In retrospect these were colorful forays into the world of fashion that provided a means to explore the Feminine, to which he was naturally attracted. Many of his early paintings built on this core imagery and presented various groupings of glamorous men and women. He worshipped the beautiful and bella figura was a priority for Harry. He perfected an interior world that sprang from his mind self-born and self-taught. Later his artistic focus shifted mainly to the written word, but his visual compositions crop up in the stage directions, and his writing has a painterly dimension and even a hyper-coloristic quality, redolent in fecund word plays and imagery.I have no doubt his perspicacious choice of Bali for his Watson fellowship year in 1978 also infused his writing and artwork with a dense tapestry of images and colors. He pursued art classes in traditional painting and lived in a cottage in Peliatan, near Ubud, with no electricity or running water. Long solitary confinements with lots of deprivations and endless access to the rich ritual life of Balinese villages set a fertile stage for creativity.

In his plays, the loneliness he projects in many of the characters, the ever present dialogue with the divine, all speak to his personal struggle with his own yearnings for recognition, for acceptance as an accomplished artist and fully realized adult. Yet it was his restlessness and the sincerity of his quest that charged his art. Whether it was growing up with a father who was schooled to be a Greek Orthodox priest, or regularly attending lengthy Sunday services in Greek, or his own inner voice, Harry expressed a spiritual calling in his writing. So when he discovered the poems of Emily Dickinson he delighted in finding a kindred soul who spoke to the divine. But it was to Sylvia Plath that he gave his poetic heart.

Wendy Wasserstein recalled a long road trip that she took with Harry and William Finn for a conference they were invited to at the Williamstown Theater Festival during which Harry kept reciting Plath by heart. He never grew out of his devotion to her as a muse and seer. In his last year (1994) he became very attached to the poems of Elizabeth Bishop. He identified closely with the voices of these three female poets. His plays are pyrotechnical displays of comedic and the poetic and are demanding on actors and directors. They are meant to be visionary, opening picture windows into a mind saturated in color and intoxicated by the divine—his favorite painting was The Burial of Count Orgaz by El Greco in Toledo. Harry was loved by his family and respected for his artistry, yet probably not so well understood. He was not alone in this condition, a gay man growing up in the middle of the 20th century.

We met at Yale Drama School. Harry Kondoleon was in his final year of the MFA Playwriting Program, when I entered for my first. To my eyes, he was the star and shining light of the playwriting corps: blindingly talented, fashionable, whip-smart, and endlessly witty, tossing off aphorisms with seemingly effortless aplomb. One of these Harry-isms—“When he dies, his tombstone will read, ‘I saved a dollar, here I lie.’”—eventually ended up in a play of my own, which he was generous enough to allow. It was like going to school with Oscar Wilde.

I never really felt glamorous enough to exist in Harry’s orbit, but he was always kind and supportive to me. Eventually, we both began to rise through New York’s Off-Broadway circles, winning the sorts of awards and grants they give to promising young writers. Five years after Yale, I invited Harry to direct a play of mine, which reminded me of his own: a family comedy that morphed into a spiritual parable. Harry agreed, and I enjoyed watching him guide actors with ease and humor, an elegant spirit who had somehow descended into our rehearsal room from a more beautiful world. In the end, my attempt at a Harry-like play was flawed, and failed to find favor with critics or audiences. Yet I still remember that production with great affection, since it gave me my most sustained opportunity to spend time with Harry, to enjoy his generosity of spirit, little knowing at the time that he would be gone just seven years later.One piece of career advice he gave me definitely paid off. “If you want to get a star to be in one of your shows,” he counseled, “you have to write a play where one actor is onstage almost the entire time, and everyone else just comes on and off the stage.” In 1988, I was lucky enough to have my first play on Broadway, M. BUTTERFLY. Sure enough, it’s one of those shows where one actor is onstage almost the entire time. We did get a star to play the lead role. And it was a hit.

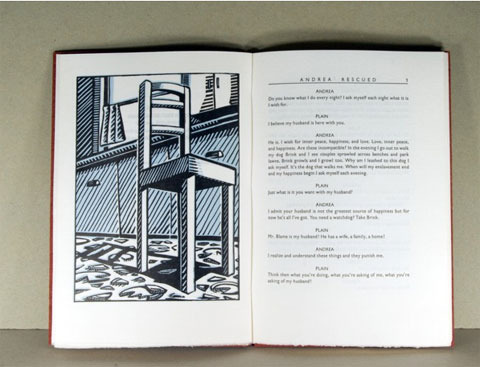

Harry was not only a great artist, but also a keen observer of the New York theatrical scene—a survivor of a world which recognized his undeniable talent, but never knew exactly what to do with him. I wish he had lived long enough to have enjoyed a Broadway hit of his own.Was it 1981? I had just started teaching playwriting at Yale Drama School and was one of the committee who’d pick the incoming class. Among the applicants was a guy just returned from Bali where he’d been for a year studying Balinese puppets and finding a new way of making theater. His submitted plays were hardly Balinese but rather skewed hilarious troubling visions of life in America. His name was Harry Kondoleon. Everyone agreed we needed Harry Kondoleon. I pictured him as an enormous hairy super-Greek like some Zorba on mind-altering drugs. We sent him his acceptance letter at Utopia Parkway in Queens, NY. September came. What a good bunch of people. Keith Reddin. Tama Janowitz. Oyama. And Harry who was more like an apparition. I had expected his fervor but not his delicacy, his grace. The anti-Zorba. More like Hermes delivering cryptic and hilarious messages from Mt Olympus. As I got to know him and love him/his work, I realized that a key to understanding him was his address where he lived with his parents who were named if memory serves Plato and Aphrodite. He grew up on Utopia Parkway, living streets away from the home and workplace of the inimitable American original Joseph Cornell who created a lifetime of boxes that contained remnants of things that were once considered beautiful but now had no other purpose in this brutal age than total discard—or else to find themselves rescued by the art of Cornell and transformed into a series of dreams that both soothed and troubled. What was in the water, the air of Utopia Parkway? Harry’s plays existed/exist as a series of dream boxes he filled with all of beauty’s most amazing and inexplicable detritus. He wrote what I consider his manifesto in a play called ‘Andrea Rescued’ which was in production when its opening was canceled:

Everything that was never in a play for you is here now here in this space fill it in. All the time your idea/feeling/remark was left out fill it in here. All the time you felt empty and out in the rain, all the time you were the one to play out-field feeling you were every year missing more and more of the bases, fill in here the short stop, pitching yourself into yourself and winning, riding shoulders and confetti. Everything left out, everything that keeps you away, bring it here, put it in.

Everything and everything and like a Sufi dancer turn it over and over around your heart spin it until you forget your feet your seat. … Aren’t you tired of sitting in the dark, of trying to drown out the nervousness of the week in someone else’s life? And the nulling of everything unable to open or close the door or cabinet, unable to pick up the covers and remove your body which lately has been a traitor to you — aging oddly, quirkish with sudden pains and low energy — remove the body from the bed, scrub it and take it to the office. Aren’t you tired of interiors, of interiors, of the slow preparation for the casket, the lid slamming shut on the giant go-wrongs, the life, the life — where did it go? This is the place to fill in the new laws, this is the place to become our own presidents and congress, to pass our own bills and come out on top.

Elect now to stop dying. Elect now to stop using your life as a way to die/as ways to stop being/as ways to cancel out, to make-go-away/as ways to being by not being by being less and less until we can disappear. The pendulum goes bad-good—good-bad—bad-bad —break the pendulum! Break the clock, all clocks!

The art on the program for ‘Andrea Rescued’ was a variation on Matisse’s Dancers. Somewhere between Matisse and Cornell: that’s where Harry lived. His death cut short a voice that is totally America, totally original and a voice sorely needed today.

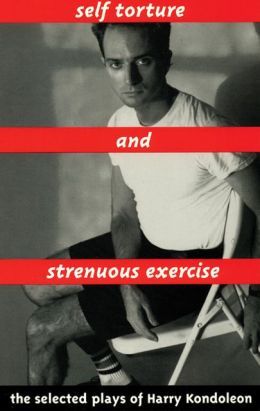

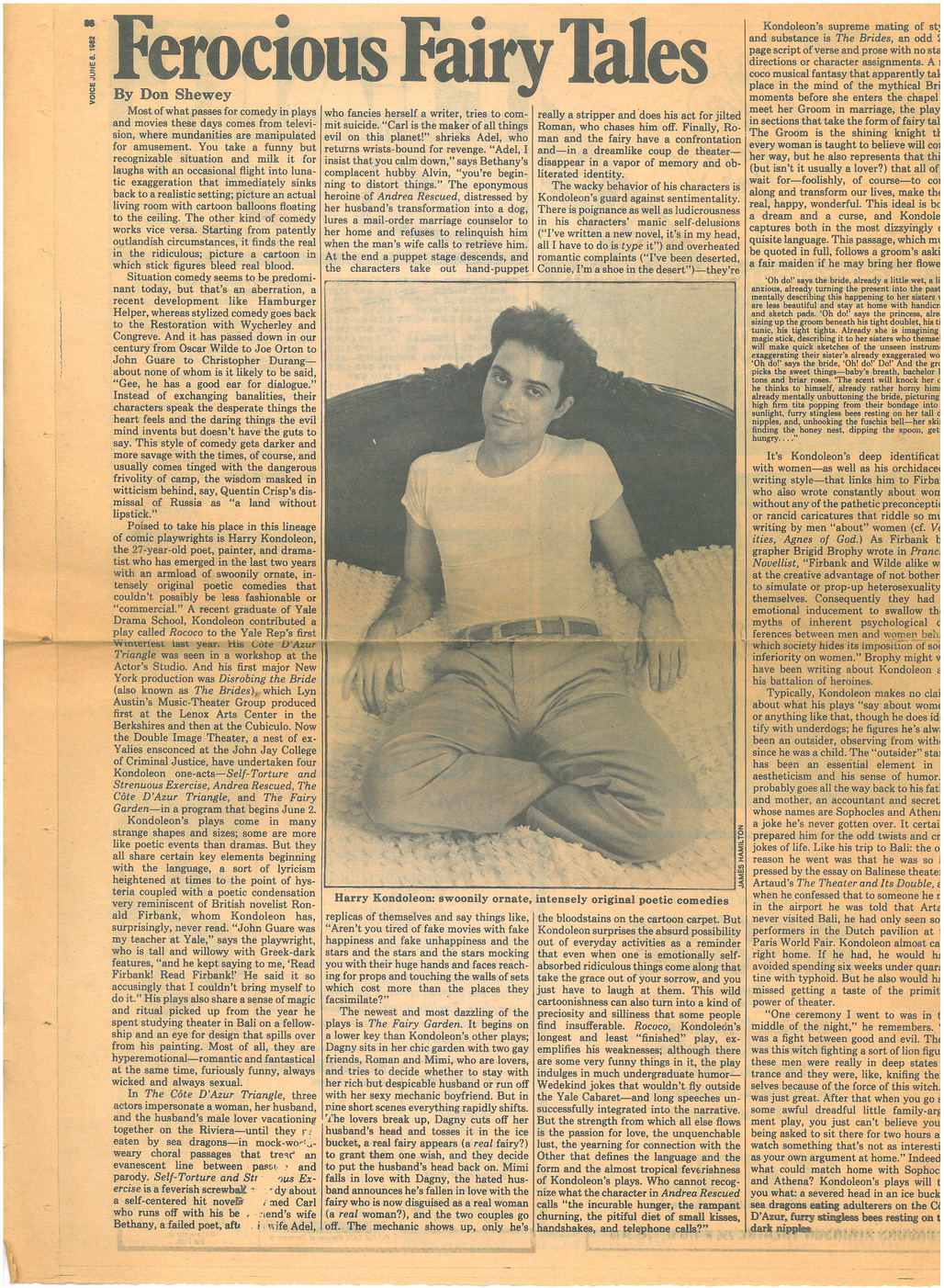

I first encountered this creature named Harry Kondoleon in the summer of 1980. As theater critic for the Soho Weekly News, I went to a storefront theater in Chelsea to cover a showcase production of Self Torture and Strenuous Exercise, his first show in New York. I gave it a rave review and in January of 1981, he dropped me a postcard inviting me up to Yale to see Rococo in the Winterfest. We didn’t actually meet until May of that year, when we briefly shook hands in the lobby of the Cubiculo Theater, where Lyn Austin was putting on The Brides. We met, again briefly, at one of the first performances of Torch Song Trilogy up on the West Side. And the following spring, when Leslie Urdang produced three of his one-acts at John Jay College, I finally sat him down for a long interview and wrote a full-page feature for the Village Voice. After that came the first Obie Award and Christmas on Mars; after that, his delirious, wonderful plays became known to the world. And I had the pleasure of becoming friends with Harry.

Harry wasn’t exactly easy to love. He could be extremely demanding, particular, contrary, suspicious, dissatisfied, and critical—of himself most of all. The only people he treated with less compassion than himself were service people, like waiters and hotel clerks, to whom he could be shockingly rude as if they were intentionally conspiring to make his life miserable. Despite or perhaps because of all that, an extraordinary number of people would do anything for Harry that he asked.

What was it about him that made you want to devote your life to him? The main thing for me I think was that Harry was a true original. I enjoyed talking about movies with him; he always saw things I didn’t. He once told me he loved Ellen Burstyn as an actress. I asked him what performance of hers he liked best. He said, “The Exorcist — that scene in the playground where she’s wearing dark glasses to cover her black eye. And she takes off the dark glasses and says, ‘I need a witch doctor.’”

He had the recording of the movie of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and had practically memorized the whole play. His favorite line was when Elizabeth Taylor says, “I couldn’t agree with you more. I couldn’t agree with you more.” We both loved Geraldine Page, for things like the scene in Sweet Bird of Youth when she says to Paul Newman, “When monster…meets monster…one monster must give in…and it will never-be-me!” Harry cherished good lines and I think drew them out of people. He loved quoting a line one of his high school teachers said to him: “Harry Kondoleon, are you only wicked? Have you no mother?”

One of the functions I played in Harry’s life was to make tapes for him. I would get an S.O.S. postcard from Yaddo saying “Help, I need a tape,” and he would make special requests, everything from Billie Holiday to trashy disco. Or he would call me up and say, “I heard this song on the radio. I want you to put it on a tape for me.” “What’s it called?” “I don’t know.” “Who’s it by?” “I don’t know.” “How does it go?” “Well, you know me, I can’t sing…duh-duh-duhduh-duh…” “Do you remember any of the lyrics?” “No. Well, something like, ‘Johnny combed his hair…’” And somehow, given these clues, I would do anything to find this song and put it on a tape. It would give me great pride to please his discerning tastes.

As the play Christmas on Mars suggests, Harry was somewhat obsessed with babies. I think he really wanted one. He loved the B-52’s hit “Song for a Future Generation,” with its refrain, “Let’s meet and have a baby now!” When his sister Christine had her child, that was definitely the next-best thing, and Harry adored his nephew Lucas.

One theatrical occasion with Harry I’ll never forget was when I took him to the Metropolitan Opera to see Cosi fan Tutte in January of 1990. In the middle of the first act, he wrote something on his program and passed it to me. It said, “I’m HIV+ and I’ve been taking AZT for two years.” Needless to say, this revelation really heightened my concentration on the opera for the rest of the act. Later I kept trying to figure out how long he had planned to spring that particular scene on me.

His illness was long and at times agonizing. Once he said to me, “If I gave you the money, would you buy a gun and shoot me?” And yet his creative juices and his hunger for the small pleasures of life (food, touch, conversation) never dried up. Toward the end of his life, he lost the sight in one eye, and he sometimes asked me to type his handwritten manuscripts into his laptop. One of those was Saved or Destroyed, which he wrote during a three-week residency at Yaddo in the fall of 1993. Except for a handful of poems, it was the last thing he wrote. At the time, he was frail and sick, and I expected a minor recap of work he had done before. Instead, he was striking out into new theatrical territory.

His last Christmas, I remember he insisted on going out with me and his friend Frank to buy a tree to decorate. He was half-blind and stick-thin, and yet leading us back to his apartment with the tree he wore a small, crooked smile of triumphant satisfaction.