I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

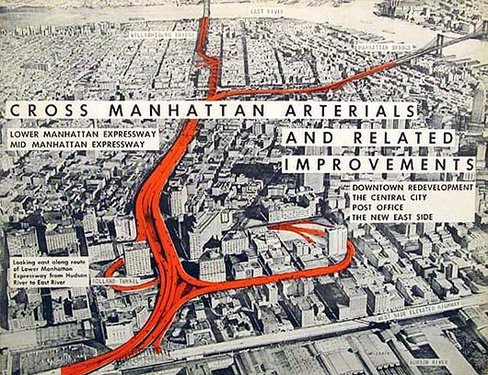

James “Jim” Brudner was a city planner, activist, journalist and photographer. Born in Queens, New York in 1961, Jim attended Stuyvesant High School before graduating from Yale in 1983 with a degree in American Studies ; involved in theatre as a high school student, he continued with those interests while at Yale. Jim’s senior thesis was titled “The Moses Method Denied: Robert Moses Meets Greenwich Village" and his love for cities and urbanism guided him throughout his life. After moving back to New York, Jim began a series of jobs working in planning and city government, including the Department of Housing Preservation and Development and the Department of Transportation.

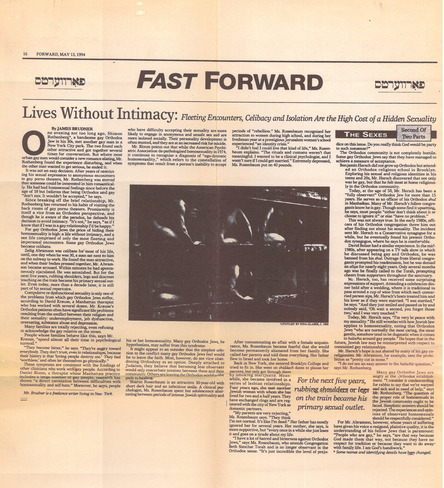

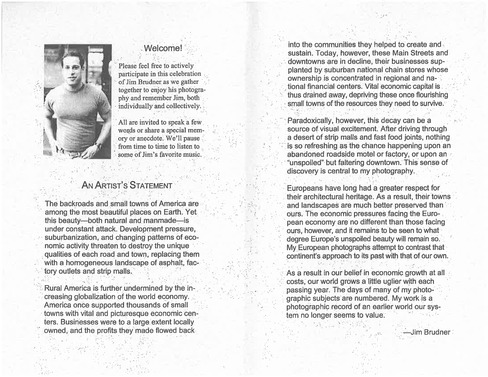

Jim’s identical twin, Eric, was a talented jazz musician and composer; he died of AIDS-related illness in 1987. Following Eric’s death, Jim became an active member of ACT UP and the Treatment Action Group. He also began to write, completing a MA in Journalism at New York University, and writing pieces about gay parenting, AIDS activism and other subjects for The Forward and The New York Times. An avid outdoorsman and traveler, Jim captured the rural, changing landscapes he visited in his photography, to which, later in his life, he devoted much of his time; in 1997 an exhibition of his work was held at LaMama Gallery in New York. In his artist’s statement , he wrote: “As a result of our belief in economic growth at all costs, our world grows a little uglier with each passing year. The days of many of my photographic subjects are numbered. My work is a photographic record of an earlier world our system no longer seems to value.”

Jim Brudner died of AIDS-related illness on September 18, 1998. He established an annual prize at Yale University that honors individuals who have “made significant contributions to the understanding of LGBT issues or furthered the tolerance of LGBT people.”

III.

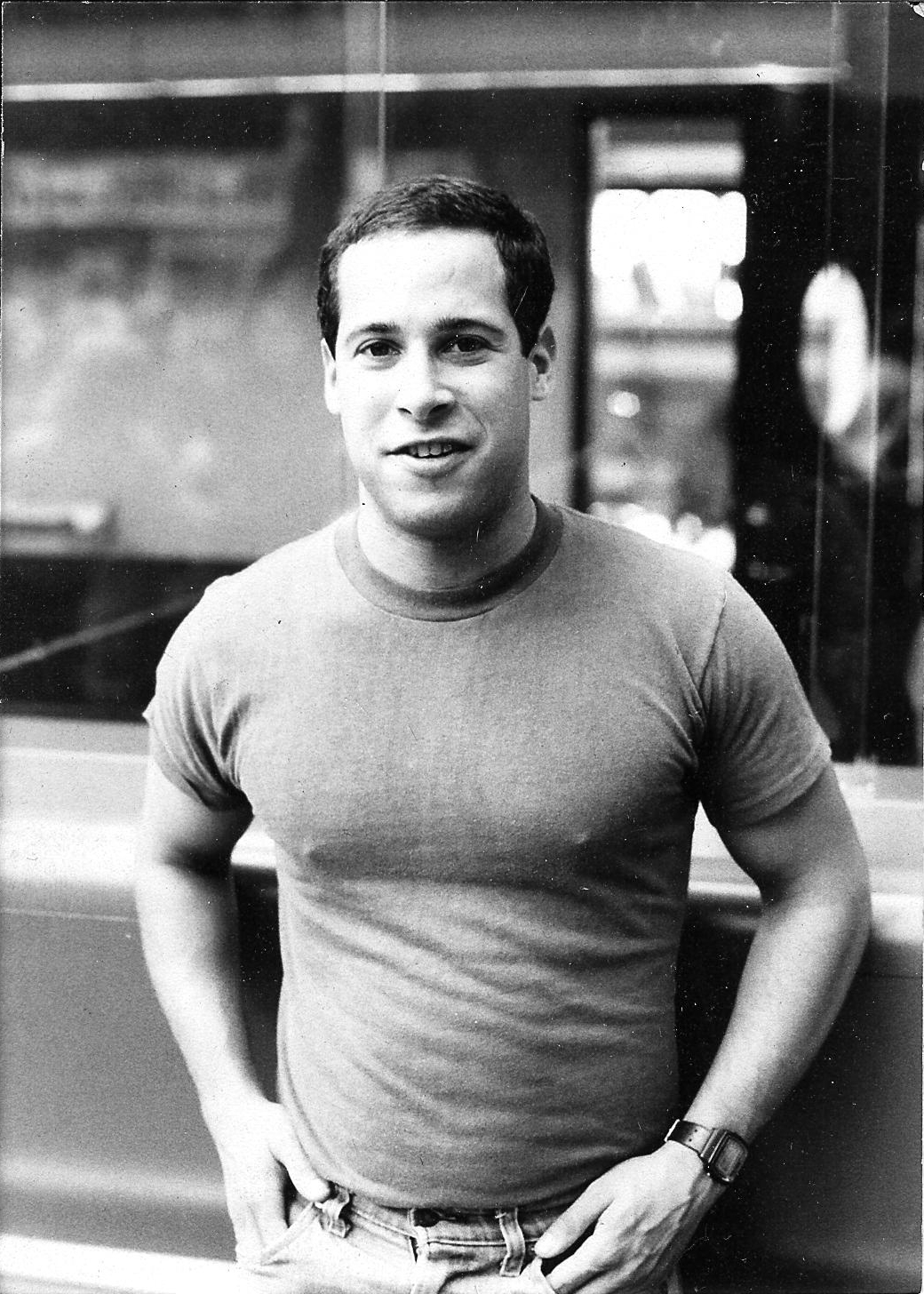

Whenever Jim came by he reminded me of an idling muscle car, waiting for someone to press the accelerator. His conversation was so full of magnetic energy that even to this day, fourteen years after his death, it persists in my head: the boyish face glowing as he makes a point (“It’s incredible! JustaMAYYYzing!”), his eyes growing large and his head shaking briskly from side to side, then forming a large circle, each sentence flanked by puffs of laughter.

At Yale I never expected nor wished to move to New York, but he talked about it with such infectious enthusiasm that after three years in San Francisco I couldn’t wait to move there. I came to see the place through his eyes, fascinated by its architecture, appalled yet intrigued by Robert Moses, addicted to the possibilities the city offered you. At Uncle Charlie’s Downtown we met and watched the boys. But we always talked about more interesting matters, too — at that boy-obsessed age a rather remarkable fact, now that I think about it.

Oh, and the gossip! This guy knew everything about everybody. But he was so sweet and generous in spirit that even his dish was filet mignon.

He was a big city boy, yet he was intrigued by my small-town roots. He was interested in anybody who might teach him something. I often think, Jesus, how many New York City students apply to Yale and get —that fact alone tells you something about what an accomplished and talented person he was. Yet I never got the impression that he thought he was smarter than me, or more deserving of being at Yale, or more deserving of anything.

Our graduation year of 1983 was the borderline between the old gay world of careless lovemaking and the new gay world of the mortal embrace. I was lucky: it was all new to me. But Jim was an old pro by then. Perhaps his fate was already sealed. In the following decade of death and dying I never shed a single tear, no matter how near to death I came, no matter how many faces I saw ravished by the disease. Today I am deeply, horribly moved by it all.

Which brings me to the characteristic I honor most about him: his complete lack of anger and self-pity when it had become clear that he had drawn one of the unlucky cards in that most unlucky deck we lived in, the life of the young gay man in the 1980s. Eric’s illness and funeral in 1987 were unpleasant reality checks for me. What else could they have been for Jim but heartbreaking, unnerving, terrifying events? Yet it never occurred to him to feel sorry for himself, though more than once he remarked at how sorry he felt for his parents.

And that is why his little business card (“James R. Brudner, Journalist, 72440.263@compuserve.com) stays in my wallet. When the disappointments and regrets that occasion middle age collect into self-pity, I pull out that card and remind myself how to live.

“You were/are a firecracker of a student. You gave me more joy than I can tell you. You’ll give the world joy, too."

This is a quote from Frank McCourt, famed author of Angela’s Ashes and ‘Tis, who was Jamie’s writing teacher at Stuyvesant High School. Jamie was a firecracker who led the freshman-sophomore classes to the first win ever for this group in Sing, an annual and hard-fought competition. He loved Show Biz and was, with his twin brother Eric, in every play and musical at Stuyvesant. One of their most successful performances was “The Brudner Twins Play Gershwin” to a sold out audience of students, faculty, parents and neighbors.

As a junior high school student, Jamie decided he wanted to go to Yale and was thrilled to fulfill that goal when he was accepted through early decision, and happily withdrawing his application from Harvard. He loved Yale – and after graduating cum laude was elated when Alex Garvin invited him to deliver a guest lecture.

While a senior, Jamie discovered that anyone who qualified could attend a music conservatory in Germany free of charge. He stayed in New Haven for the summer in order to take a cram course in German (a language with which he was totally unfamiliar.) When the course was finished, he packed his bags and bike and flew to Germany, confident that when he auditioned at the Leopold Mozart Conservatorium in Augsberg he would be accepted. And he was.

He spent the following year studying music and travelling all over Europe. He met his mother in London where she was taking a theatre course. And, of course, this provided an opportunity for him to enjoy some fine dining and unexpected touring.

When he returned home after his year abroad, it was time to look for a job. He had an unusually strong belief that he had a great deal to offer the public, and decided that the best place to do this was by working for the City of New York. He worked for several different city agencies, and although he was not a lawyer, he wrote and negotiated two contracts for the Department of Transportation that saved the city $8,000,000 per year.

He decided to pursue a Masters in Journalism. When asked why he chose New York University and not Columbia, he had a genuine “Jamie explanation.” He announced to us that after four years of being taught the theory of every subject he studied, he was looking for teachers who had real-world experience. He believed that NYU offered a journalism faculty of real reporters and news men and women rather than the theorists he would find at Columbia. He briefly worked for the Stanford Advocate but felt he could do a better job by continuing to work for New York City, and returned.

He continued to write free-lance articles. He worked for a committee of the National Institutes of Health on AIDS research and travelled around the United States attending meetings on this subject. He was the only member of this group who was neither a medical doctor nor a psychologist. One of his abilities that was highly respected by the group was his ability to write reports and other technical materials in understandable English. During this time, he wrote an Op-Ed piece for the New York Times explaining the science behind the then current AIDS research.

He loved to travel across Europe and the United States taking photographs of towns, buildings and people that he found interesting. He later had a successful show of his photographs at LaMamma Gallery in Greenwich Village.

When his brother, Eric, died, we set up the Eric Brudner Memorial Music Fund at Brown University, his alma mater. This fund was organized to provide for a free annual concert at Brown University for students, faculty and the people of Providence, Rhode Island. Eric became a working jazz pianist while still an undergraduate and had won the major music prizes at Brown. The objective of the concert was to bring in well known, working jazz musicians to work with the music students and participate in the concert together with the Brown Jazz Band.

Jamie always brought a large contingent to the concerts. And when he knew he was ill, he wanted to create something that would not put an additional emotional burden on his parents. That was the genesis of the Yale Brudner Prize.

Jim Brudner was part of why I came to Yale. I visited as a senior between rehearsals for my high school’s production of “Pippin.” While waiting for an interview I wandered into a piano room and was plunking out the melody for “Corner of the Sky” with one finger when a ball of brunet energy with flashing eyes rushed by, stopped, turned, and said, “You’re doing that wrong! Let me show you.” Leaping onto the bench Jim glanced at my score, played the first full page beautifully while singing it better than I ever would, then started riffing off jazz interpretations. By the time he finished with an impish smile I had decided that a) I would attend Yale and b) somehow I’d find a way to date that handsome rogue.

One out of two ain’t bad.

I took some time to mourn the fact that Jim would never be my Boyfriend. But he quickly became a good friend, and a guide to a more roguish, raucous and joyous approach to life than I had known before that. Jim took me to Partners, New Haven’s first gay bar, where I became a favored mascot “fag hag” and learned to dance with real abandon, unfettered by dating concerns — as Jim did, dating concerns or no. Jim introduced me to Freud and Jung and dream interpretation during his stint as a Psychology major, which he dropped summarily when he felt he had "learned enough” about himself (he finished as an American Studies major, enjoying both the broad canvas of American culture and being able to say “I’m Am Stud”). Jim taught me proper weight lifting, which he did regularly to keep fit and keep at bay pain from an old back injury, but also because, as he said, “One should never underestimate the pleasures of a good endorphin high.” He helped me experiment with other highs as well, teaching me that experience with altered consciousness, properly channeled, can help strengthen conscious awareness.

I recognized early that Jim’s full-bore zest for life and all within it was indivisible. The energy that made him an accomplished jazz pianist, artist, photographer, weight lifter, cross-country bicyclist, advocate for the handicapped and for gay rights, great friend and much else was also the energy that drove him to try anything and everything that might bring new bite, new excitement to life. When helping clean out Jim’s apartment after he died, another friend (Steve) and I found a black Hefty garbage sack filled with thousands of clothes-pins. I haven’t the faintest idea what Jim did with those clothes-pins, but Steve and I found some breathless and much needed laughter trying to imagine what experiments Jim might have gotten up to with them.

In some ways my quintessential personal memory of Jim was the day he first tried LSD and asked me to babysit in case his trip went bad. He was a junior in college then, excruciatingly handsome and dressed nattily for the occasion, his curly hair bouncing with excitement as he savored the flavor of the tab. Then he sat at his piano and played softly while the drug took effect, remaining a lucid commentator who noted joyously as the musical sounds for him grew colors, and sprouted wings. His playing, if anything, became more beautiful. I remember thinking at the time both that I would never want to take the flashback risks of acid, and that because Jim was willing to take those risks he was having a richness of experience that I envied. His trip was a good one. His trips nearly always were.

In thinking of Jim I’ve often come back to Pippin: “Everything has a season, everything has its time. Show me a reason and I’ll soon show you a rhyme….” Jim’s life ended far before its season, yet he lived more fully in his few years than did many who have out-aged him by decades. I’m now getting close to twice the age Jim was when he died. I’m happily married, a parent with a decades-long career, property, and retirement accounts. Jim never got to experience those joys, a fact I still mourn. But I can’t mourn one iota of the full-throttle excitement and wonder of his life. I miss him still.

It’s the early ’90s at a party hosted by a mutual Yale friend, Steve Carlin. Jim is explaining the behind-the-scenes machinations that plague the redesign of the sidewalks of Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village, making it clear that 1) though he worked as a policy analyst at the NYC Department of Transportation, this was not his project, and 2) despite some noble efforts, not all of his colleagues are as dedicated and skilled as he is. I play the pushy, pissed-off local a little too realistically, and Jim’s exasperation builds. Our disputation, our debate—the kind of heated verbal tussle Jim thrived on—soon expands to embraces politics, pragmatism, philosophy. Despite, or because, we nearly come to blows, I know immediately this is a person I want to have in my life.

Jim grew up on the subways and could easily have decked me. He was proud of his musculature, having recently shed the extra pounds he put on after his twin brother, Eric, died of AIDS; but he knew that words were his best weapons. He expertly deployed both whenever he went out cruising.

He was wise; I learned much later that beneath his confident and hyper-articulate demeanor, he was smart enough not to hide his vulnerabilities (at least some of them) from those he trusted. He was also insatiably curious. He wanted to know how everything worked, and how it could be made to work better. Then he would explain it all to you in an avalanche of details and connections, and ask more questions. In urban planning and AIDS policy, for example. Or what he saw when he drove through rural America with camera in hand. Not averse to self-promotion, he could tell you, to the exact dollar, how much money he saved for the city when he managed bus routes in Brooklyn and Queens. This was actually kind of endearing, mostly because Jim loved to laugh at his own eccentricities.

Living with HIV, Jim drafted his many friends into an extensive support network. He knew exactly how each of us would be able to assist him, and he did not hesitate to ask for help. Because Jim and I lived only a few blocks apart, he sometimes called me on his way to the emergency room with a minutely detailed list of instructions— what books to gather, where to find extra pairs of socks, which magazines to hide from the cleaning woman. This happened more than once, so when Steve phoned to tell me Jim had been admitted to St. Vincent’s with what would be his final illness, I naturally assumed that once everyone did what Jim needed them to do, he would be home in a few days’ time.

One December, Jim and I both decided we were through with the New Year’s Eve bar-and-party scene. A better plan: We would celebrate together quietly, just the two of us, with Chinese take-out and a rented video. Jim came over bearing Taxi Driver. It’s a dark and violent film, an odd holiday choice—but then, Jim was an urban anthropologist who got a charge from the film’s depiction of the streets just a few blocks east of his apartment as an expressionistic jungle. And as a composer, he was enamored with Bernard Hermann’s score. At the stroke of midnight we shared a champagne toast and a good, long hug.

Perfect.

Then, sheepishly, we headed out separately to the very parties and bars we had lately scorned. We laughed about it soon enough, and looking back, that’s the evening I first realized I loved Jim.

Jim was my big brother, my confidant, my role model. I wish he were here today, writing about politics, playing the piano, photographing abandoned storefronts, explaining how cities function, saving money for the taxpayers. I miss Jim terribly, and I love him still.