I.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

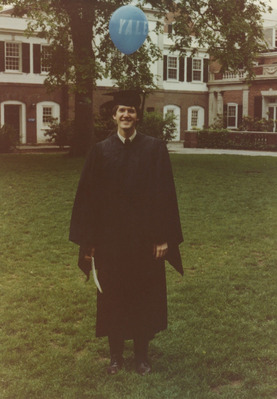

John Wallace was born in Princeton, New Jersey on July 22, 1960. From kindergarten through fifth grade, he attended the Littlebrook Elementary School; for middle and high school, he attended the Princeton Day School, where he starred in a number of theatrical productions. He enrolled at Yale in the fall of 1978 as a member of Berkeley College, graduating four years later with a degree in American Studies

An avid singer and actor, John was drawn to performance from a young age. At Yale, he became a member of the Spizzwinks(?), an a cappella group. After his junior year, he spent a transformative summer in San Francisco, where he came to embrace his homosexuality while working for Mother Jones. The following fall, he became a visible—and beloved—icon of gay identity on Yale’s campus, joining the LGBT Co-op and participating in a number of political actions, including the campaign to convince the University to expand its nondiscrimination policy. He also worked to unionize Yale secretaries.

After graduating, John moved to New York, where he began to freelance for magazines and TV. He worked as a writer for Channel 13, and penned articles for The Village Voice, GQ, and other publications.

In New York, he met and moved in with the playwright Lem Borden. The couple bought a house together in the Catskills.

John died of AIDS-related causes on February 28, 1990. He was 29 years old.

III.

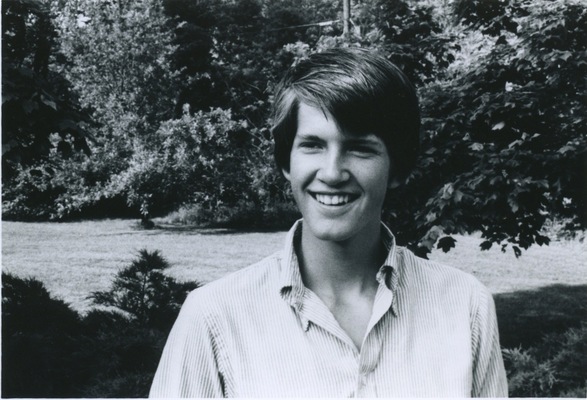

The first thing I noticed about John Wallace was his haircut. It was asymmetrical, with bangs that jutted straight out, but then took a sideways dip, like the flap on an airplane wing. It was the coolest haircut I’d ever seen.

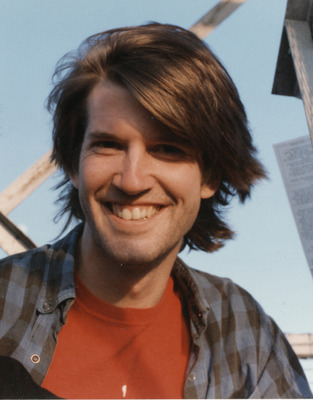

The second thing I noticed about John was his kindness. He radiated warmth. I remember thinking that it was deeply unfair that anyone that handsome could also be that smart and that kind. He had just returned to Yale from San Francisco —and this also struck me as unspeakably glamorous. Of course, I fell completely in love with him.

One day, I got my courage up to ask him out for a coffee. At some point, I just blurted out my declaration of endless love. This seemed to happen to John on a regular basis—and he couldn’t have been sweeter about letting me know that it was likely that we would, in the near future, just remain friends.

Despite his kindness in letting me down easily, I was so mortified and disappointed that I went straight to the New Haven train station and got on the first train out of town—to Boston, where I camped out for a day and night with a friend before returning to Yale, finally able to see the humor in it all.

John greeted me especially warmly the next time we saw each other, as though I was one of his closest friends. No awkwardness whatsoever. We talked about all sorts of nonsense—and laughed.

I’m reminded how much I miss John whenever I see the final scene of The Normal Heart. Grasping for a ray of light in a moment of darkness, Larry Kramer’s protagonist tells his dying lover about recently attending one of Yale’s first gay dances, presumably offering the image of a dance floor full of healthy young gay men as a symbol of innocence and hope. I’m pretty sure he’s referring to the dance where John and I broke up in April 1982, the big finish to Yale’s first Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days, where Kramer had been a special guest.

That year John pretty much personified gay awareness at Yale, returning from San Francisco with a new haircut and an assortment of outfits that celebrated being gay in a radically unapologetic way. He was hard to miss, the golden boy in leopard-skin tights, blue eyes challenging anyone who questioned his right to his bright gay future. And he terrified me—even more so when he picked me, his physical and temperamental opposite, to share his spotlight.

John’s interest was so unexpected that I didn’t even realize that our afternoon tray-sledding down the D-school hill was actually our first date. He pursued me with characteristic focus, reveling in our being the gay Mutt and Jeff of the American Studies department, preparing to save the world with cultural criticism. By the spring he had me nervously helping him petition Yale to change its non-discrimination policy. Our romance came to an end that April, in dance floor drama that John and I later laughed about.

In truth, we were struggling to cope with feelings and circumstances we were ill-equipped to manage: I was still grieving the man I had been involved with back home, who had died the previous fall. John had focused his considerable life force towards trying to help me move forward from my loss, but we lacked the tools we would all soon be forced to develop.

I grieved for John again returning to The Normal Heart last year, its final image a reminder that the promising young men on that dining-hall dance floor were already dealing with loss and untimely death, and learning how to fight the institutions that were supposed to support and protect us.

John proved himself as an extraordinary fighter in the years that followed, maintaining hope and even his own sense of innocence while circumstance threatened to rob him, and our generation, of both. He was always stronger than he looked.

At the 2009 Yale LGBT Reunion, I gave a talk entitled AIDS and Remembrance: Days of 1984. Among a litany of memories from the early years of the AIDS epidemic, I said this:

I remember that John Wallace, the most gorgeous man in my college class, tried everything, but I can no longer remember everything he tried—just the experimental penicillin shots, mega-doses so painful he couldn’t sit for days but which turned out to be useless; the cleansing macro-macrobiotic diet that made his skin turn grey but which turned out to be useless; the bitter melons everybody fought so hard to secure but which turned out to be useless—and then one afternoon Lem called me at work and said, “Come quick, no, not after work, now,” and I ran down 44th Street, clutching a yellow legal pad, what I could offer the dying. Our senior year at Yale, John and I had been in an American Studies reading group together, and I sat across the seminar table mesmerized by his beauty while everyone chattered on about the social significance of Barbie dolls and Graceland and My Mother the Car, and now, not even a decade later, I was kneeling by his bedside scribbling his dying wishes. And then Lem died, too. And then the man I met at Lem’s memorial service, and dated, briefly, died. And so on.

John’s plight was emblematic of an era. He was also my friend and I miss him.

-

- Spizzwinks(?)

- Co-op

- Class Poet

- Scholar of the House

- Volleyball

- Elihu

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Yale Literary Magazine

- Yale Daily News

- Gay Alliance

- Summa Cum Laude

- Whiffenpoofs

- Russian Chorus

- Tutoring

- Skull and Bones

- Yale Political Union

- Dwight Hall

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Silliman Chorus

- Yale Glee Club

- Book and Snake

- Yale-in-China Association

- Yale College Dramat

- Aurelian Honor Society

- Swim Team

- The Criterion Board

- The George Orwell Forum

- The Yale College Democrats

- Saybrook Dramat

- Gymna

- Gymnastics

- Cheerleading Team

- Yale College Council

- Yale Political Union

- Key Society

- Elizabethan Club

- Yale Episcopal Society Student Committee

- Manuscript

- Phi Beta Kappa

- Basketball

Our son John was an excellent writer and covered diverse subjects with equal interest and fervor. He aspired to be a great writer and was on his way there, contributing through different media. In addition to writing articles for the Village Voice, Mother Jones, and GQ, he wrote copy for public TV and created brochures for architecture firms.

John enjoyed helping other people, especially young kids, who adored him. He was a “Big Brother” while at Yale and spent summers working at the Yale Co-op. He also enjoyed having fun, especially if it involved performance. He was a member of the Spizzwinks(?), and performed in many plays and musicals. John was unconventional: he had a great sense of humor, and made us all laugh, even when things weren’t all that bright. And he was strong—he didn’t let his illness get the best of him psychologically. He kept us all going, even in the worst of times.

My big brother Johnny was a rock star. This was no small matter to my pre-teen self, because having a sibling in the twelfth grade who was good-looking and funny significantly upped my sixth grade social status. Just being able to say hi to Johnny and his friends as we passed each other in the halls of our school made me feel special. Because Johnny always had time for me, so did his friends: pretty cool to be a sixth-grader sitting on what we called “the bench” with the Seniors.

Johnny reveled in the performing arts. From his playful rendition of Snoopy in You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown to his convincing portrayal of an uptight Lord Evelyn Oakleigh in Anything Goes, Johnny embraced each of his characters and routinely ”brought down the house.” I went to his plays time and time again just to see and hear him adopt these alter egos. Because he would practice at home, the whole family got involved. I would commit his songs to memory right alongside him. How important did I feel reading the lines of Charlie Brown so he could learn his Snoopy?

Johnny’s fellow cast members would hang around the house before rehearsals or after a cast party. As if not wanting the show to end, they would regale us with stories of miscues and mishaps. Being a savvy guy, Johnny was always aware of the crushes I had on his co-stars and would allow me ample time to linger. Instead of scootching me out of the room when John Patterson, who made my knees quiver, had spent the night, Johnny let me sit and gawk as they ate breakfast at our kitchen counter. Rather than keeping his world to himself, Johnny shared it.

John and I were grade school classmates. In our pre-gay way, we shared a mistrust of the rituals of male adolescence around us, but were equally wary of the potential faggot inside of each other. We didn’t become close until after college when we reconnected in New York through mutual friends. We were young, we had survived the gauntlet of coming out, and we were eager to consume whatever cutting edge culture we could find. Watching all of Einstein on the Beach from the upper balcony at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, or listening to a bootleg copy of a Laurie Anderson concert with the Oakland Youth Symphony, we were ready for life in the big city.

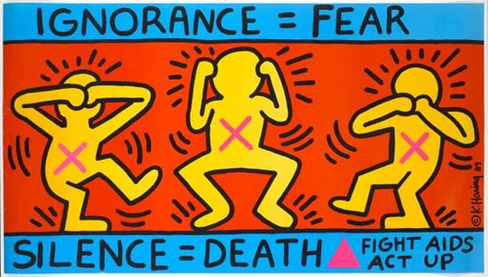

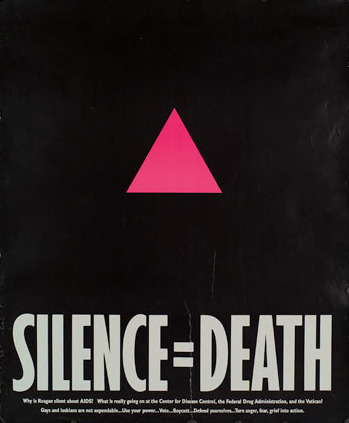

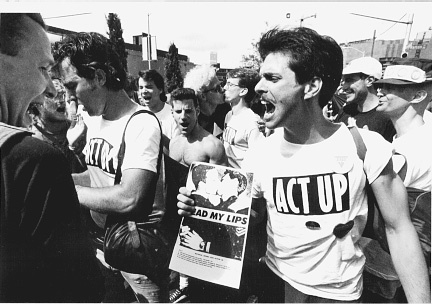

AIDS surrounded us but was somehow equally amorphous; there was fear but no clear guidelines in the early eighties about how exactly to conduct oneself, short of complete abstinence. I became involved with ACT UP because I needed a way to ground my anxiety about HIV, but also to locate a community. When I joined, I hardly knew anyone personally who’d been affected. At the time, John was working for Channel 13, programming the interstitial spots between shows, and writing for the Village Voice. Sometime in the fall, I spent a weekend with John and his boyfriend Lem in the country. Climbing a hill behind their cabin, John struggled for breath. Soon afterward, he was diagnosed with pneumonia, and then full-blown AIDS.

How completely unprepared I felt for knowing how to help John as he grew ill. I recall taking him to the Whitney Museum in a wheelchair one afternoon; we all wanted to pretend that life was normal. John chose to venture out into the world, even though his energy vanished halfway through the outing. That was a time when, if you were pushing a young man around in a wheelchair, you got stares—others knew what was going on, and it freaked them out. The ravages of AIDS were visible; you didn’t need to look far for a reason to fight for a cure. I regret not having had the language to express the helplessness I felt, the fear for myself, and the despair of losing my friend.

I wish John were around to share the experience of growing older, to look back on our younger selves with humor and forgiveness, to observe where life had taken us. I would like to have read the writer he’d have become.

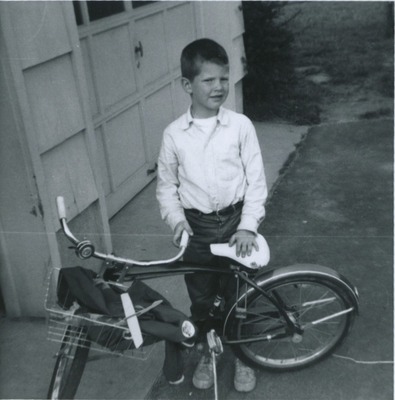

I knew John from playing cello with him in the fifth grade orchestra. We fifth grade girls viewed John as a kind of Charlie Brown: his head was round and seemed too big for his body, and, like Charlie Brown, he was sweet, harmless, and a little clueless. We lost touch.

Imagine, then, my surprise when, during my first week at Yale, I met a blindingly handsome, animated, and tall blond dashing up the stairs in Vanderbilt Hall, who turned out to be the same John Wallace.

John’s next transformation took place when came out of the closet to his friends after spending a few months in San Francisco. He came to see each of us individually to tell us the great news: I remember him bounding up the stairs again, this time in my off-campus apartment building. His joy was contagious; everything had come into focus.

Then came John’s last, devastating transformation. Although he weathered the harrowing phases of AIDS with unbelievable grace, the physical toll of the disease was crushing. In one phase, illness and medication had swollen his face and thinned his hair. He began at 28 to resemble once again the Charlie Brown he had been at 10.

During his few short years between college and death, John worked tirelessly to establish himself as a freelance writer. He called me once to say he’d been assigned to write an article for GQ about ear care, and was collecting as many ear care stories as he could. Ear care! But he was a writer and could turn anything into lively prose. I will always think about what a great writer he would have become.

No matter how old he would have grown, John would never have lost his boyishness. He wouldn’t have become elderly—he would have become a boy who had grown old. I knew him when he really was a boy—in middle and high school.

I still think of John in constant motion, long legs and whirling arms. There was a certain puppyish quality to him, lots of big teeth and scraggly hair. He sniffed and bounced around, trying to figure out the way the world worked. And, puppy-like, he grew very quickly so his brain wasn’t always working in concert with his new body. We both spent a lot of time tripping, clunking heads, and crashing into things. When this happened, his laugh sounded like someone joyously gulping down water.

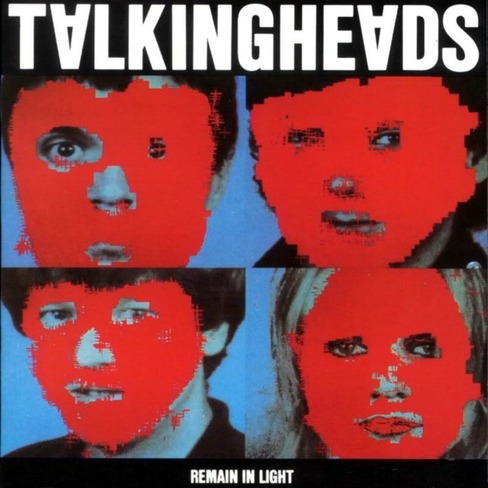

Like any self-respecting teenager, he was a mass of contradictions. His goof factor was high but so was his intellectualism; he wore Nantucket Reds but was an early adopter of the Talking Heads; he careened between the genius crowd and the jocks, the cool girls and the marginalized boys. Restless and inquisitive, he was a theater jock, a newspaper editor, a geek, a god, popular and unpopular depending on the day of the week.

Growing up, John’s wicked wit and self-deprecation masked a self-consciousness. It was wonderful to see him shed that quality at Yale, where his contradictions slowly folded in on themselves. Once liberated from all that questioning, he found the space to redirect his optimism and energy into a life force that we all hoped was infinite.