I.

-

- Poet

- Artist

- Architect

- Writer

- Journalist

- Musician

- Professor

- Philanthropist

- Banker

- Activist

- Lawyer

- Accountant

- Teacher

- Playwright

- City Planner

- Scholar

- Art Historian

- Museum Administrator

- Psychologist

- Administrator

- Diplomat

- Doctor

- Graphic Designer

- Ecologist

- Dramatic Literature

- Administrative Director

- Director

- Director of Development

- Consultant

- Interior Designer

- Publisher

- Financial Officer

- Composer

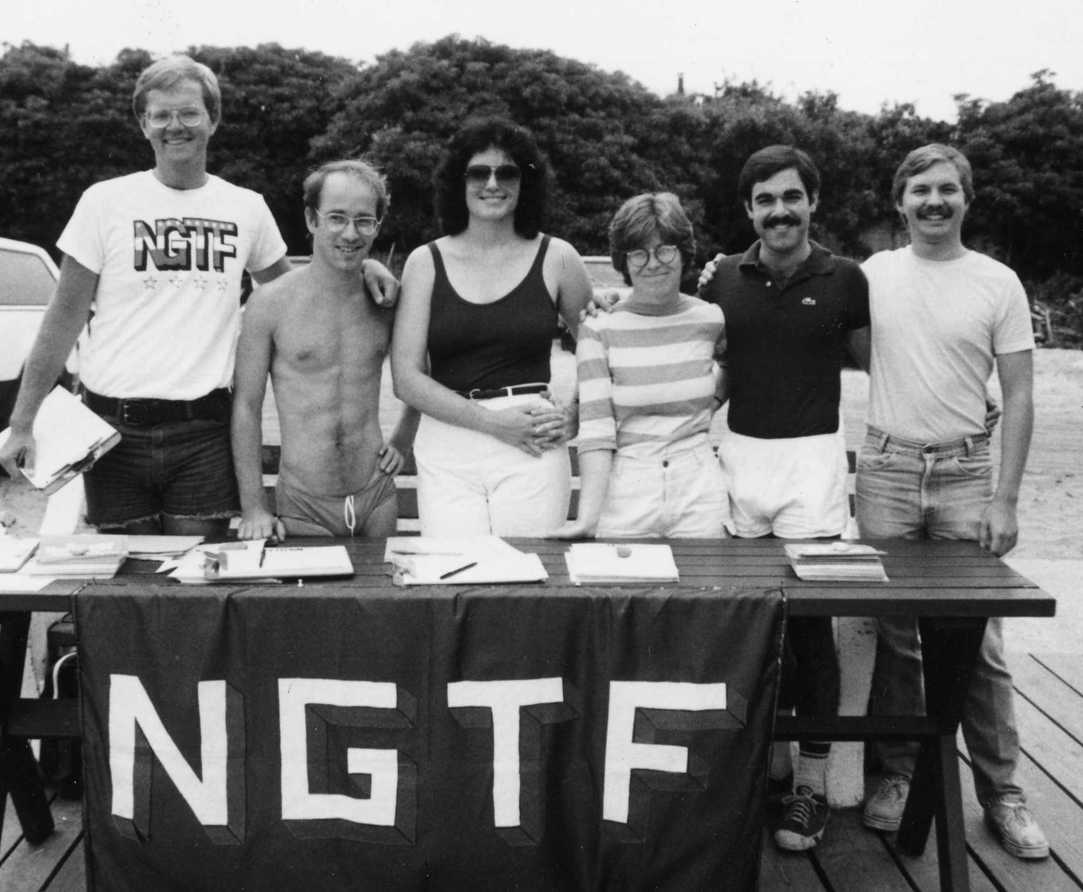

Gerald (Jerry) Bruce Olanoff was born on December 11, 1952, he was raised on Long Island and later in Queens before attending Yale, where he graduated in 1974. He moved to Manhattan where he met his partner Ron Csuha, an artist. Olanoff then pursued a master’s degree in architecture at Columbia University, receiving it in 1977. During those three years, Olanoff became active in in National Gay Task Force.

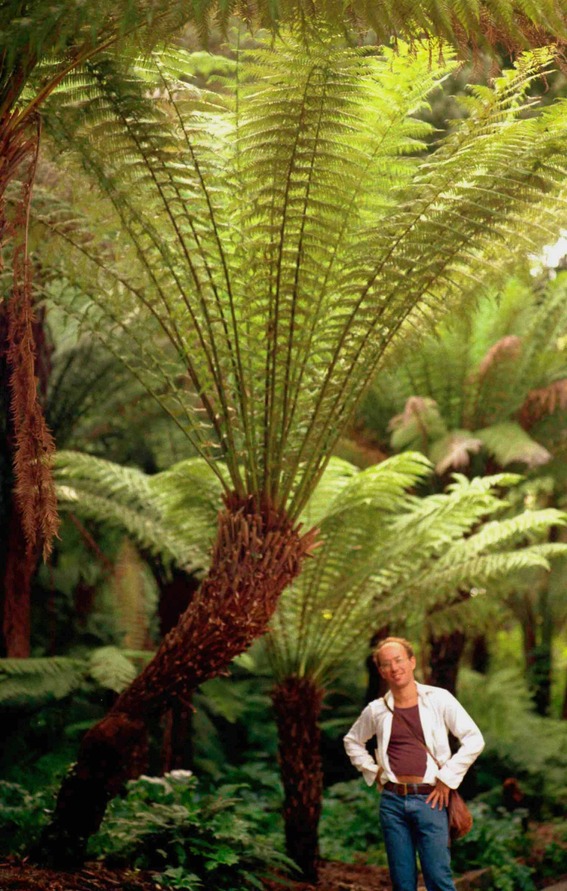

Olanoff spent several years working at the firm of Phillip Johnson and John Burgee, but was not satisfied with his progress as an architect there. He moved to Davis, Brody & Associates in 1979; Here, Olanoff was much more comfortable and became project architect for the design of new conservatories and the renovation of the old conservatory at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden which were completed in 1988. He was also a project architect for the renovation of the old Bird House at the Bronx Zoo but had to leave this when he was no longer able to work because of AIDS.

Olanoff was diagnosed with AIDS in 1986, and started getting major health problems in 1991. Davis Brody was very supporting of gay architects and luckily Olanoff was able to continue working longer than most because of this support. Even after his diagnosis, Olanoff was made an associate of the firm.

On April 3, 1994, Olanoff was featured in a New York Times article on the effect of AIDS of architecture firms: AIDS and the Practice of Architecture, written by his friend David W. Dunlap.

While working for Davis Brody, he was also able to work on the design of homes for private clients in New York, Massachusetts, and in the Pines on Fire Island. Five of these houses were built in a modern style using traditional materials of wood and stone to achieve large double height spaces to serve as living rooms. The plans for the design of these houses are archived at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University.

In 1983, Jerry became a founding member of the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in Greenwich Village, and headed the architecture committee to deal with design problems in the building acquired by the Center, the former Food and Maritime High School on 13th Street in Greenwich Village, NYC. The committee was responsible for the building’s first renovation, which began in 1995.

Olanoff was an outspoken activist who disliked having had to hide his identity so much so that his life seemed to truly embodied the ACT UP slogan “Silence is Death.” He was highly indignant at the ways gays were treated during his life, chiefly among these treatments being the way a family of one partner could legally confiscate assets of his or her gay union. Though he was an activist, he was not a member of ACT UP, but greatly appreciated their work. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, he and his partner Ron marched regularly with Act Up in the annual Gay Parade.

Olanoff died on October 22, 1995 from AIDS related complications. He was 42 years old.

This profile is in progress. Click here if you would like to make a contribution.

II.

My son, Jerry Olanoff (Class of 74)

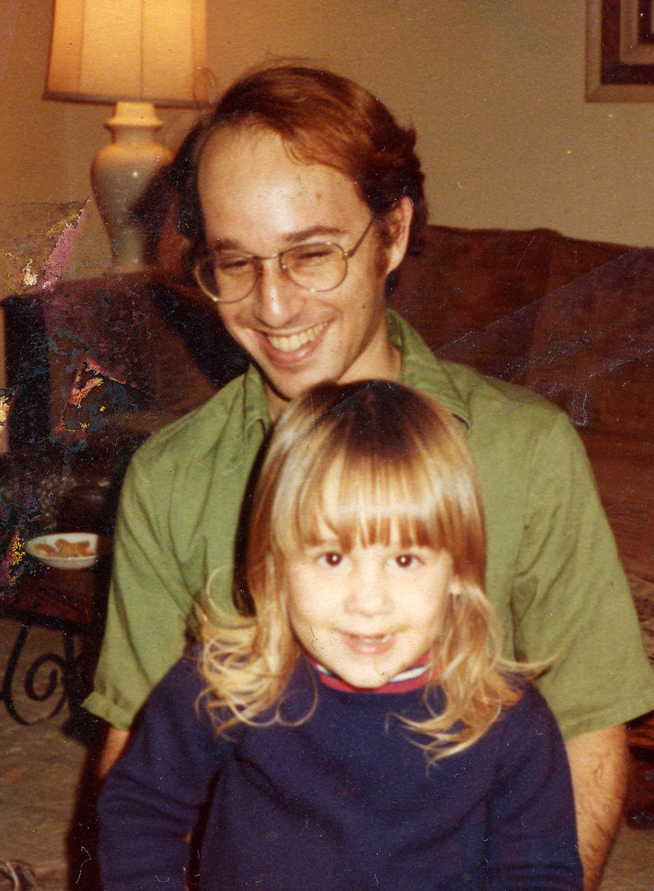

It is almost twenty years since my son, Jerry, has died. He was a wonderful person, bright, warm sweet natured, cared about deeply by those who knew him. It was extremely difficult to say good-bye to him. He was a very inspiring person. We still grieve for him.

After he graduated from Yale, he attended Columbia University Architecture School and completed the three year program. He became a member of A. I. A., enjoyed working as a creative architect in New York City and privately. His designs are still enjoyed by those he worked for.

Jerry was fortunate in having a loving relationship with his partner, Ron Csuha, and they were together twenty years. Throughout his illness, Ron cared for him in every respect. I am still in touch with Ron via telephone, every week as I deeply respect this fine person.

It was a fulfilling love that he and Jerry shared.

My brother Jerry, (Yale 1974) was my only sibling, born 3 years after me. I always appreciated his intelligence, zest for life, humor and passion for human rights. Yet it wasn’t until after he had died that I realized he had wonderfully modeled a different and very healthy kind of masculinity.

Jerry’s passion for gardening, reading, dancing, cooking and especially for maintaining close friendships embodied his humanity. As I continue to re-define my own masculinity, deepen my friendships, and work passionately for the rights and dignity of all human beings, I thank Jerry deeply for all that he was.